Who Has the Best Housing Plan?

Canada has a housing shortage. Who has a plan for housing abundance?

I hope everyone had a pleasant Liberation Day.

I’m coming to you from overcast Kingston, Ontario, where Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre is campaigning.

All party leaders have spent the past 24 hours scrambling to respond to Donald Trump’s quixotic tariff announcement — which, conspicuously, left out Canada and Mexico. While we still face a litany of sector-specific tariffs, everyone is cautiously wondering when the other shoe will drop.

But today’s dispatch is about something else: Houses. Specifically, a lack of them.

While the line between a continental trade war and home prices might not be an obvious one, I consider myself a housing fundamentalist. That is: All of our woes trace their lineage, at least partly, to our shortage of housing; and all of our woes can be addressed, if not solved outright, by building more homes.

Our housing shortage makes us poorer, less productive, and more anxious. It worsens income inequality and reduces upward mobility. It drives anxiety towards immigrants, creates crime, and drives social and political polarization. It makes it harder for us to fight climate change and hampers technological innovation. Perhaps worst of all: It makes people homeless.

That problem has been met with an abundance of promises from Ottawa to get new housing built, and yet a shortage persists.

The mismatch between crisis and response has made people insane. And rightly so. It has made our federal government look deeply ineffective and extremely inefficient and it has driven the belief that we can no longer, as a country, do anything.

It is true that in Canada, the federal government is not primarily responsible for housing. And yet during our last big housing shortage, it was Ottawa who stepped up to solve things. And it is also true that the federal government has considerable tools to help get housing built — through the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation, federal transfers to cities and provinces, public transit funding, and a plethora of other subsidies, grants, programs, and initiatives.

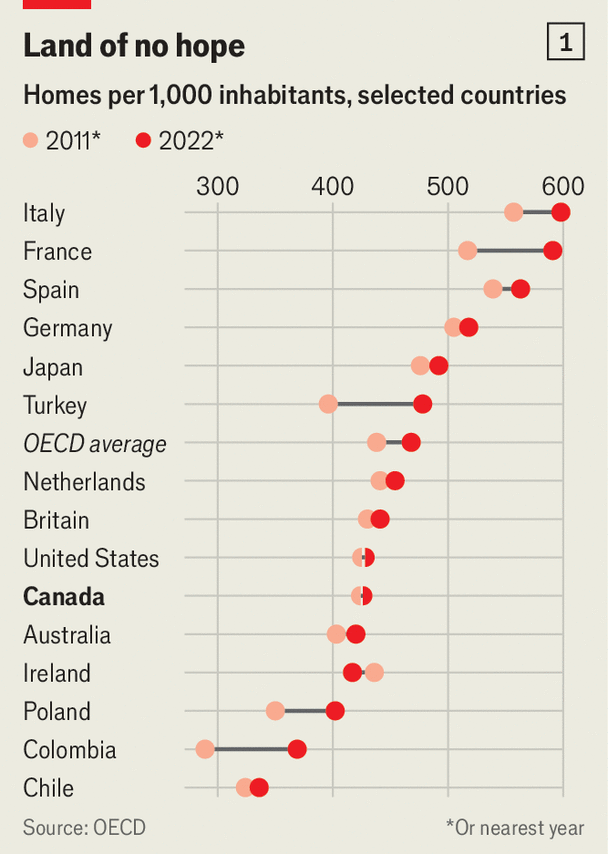

The origins of the housing crisis are no secret: We kept adding people to the population without building homes for them.

In 2008, Canada added just over 320,000 new residents to the country. That same year, it completed just under 215,000 homes. The ‘08 financial crisis depressed home construction in Canada, and it would take until 2021 for Canada to get back to that same rate of building. Today, we are struggling to even sustain our level of home construction. While many problems in this country can be attributed to COVID-19, not this. In fact, we got better at building homes during the pandemic.

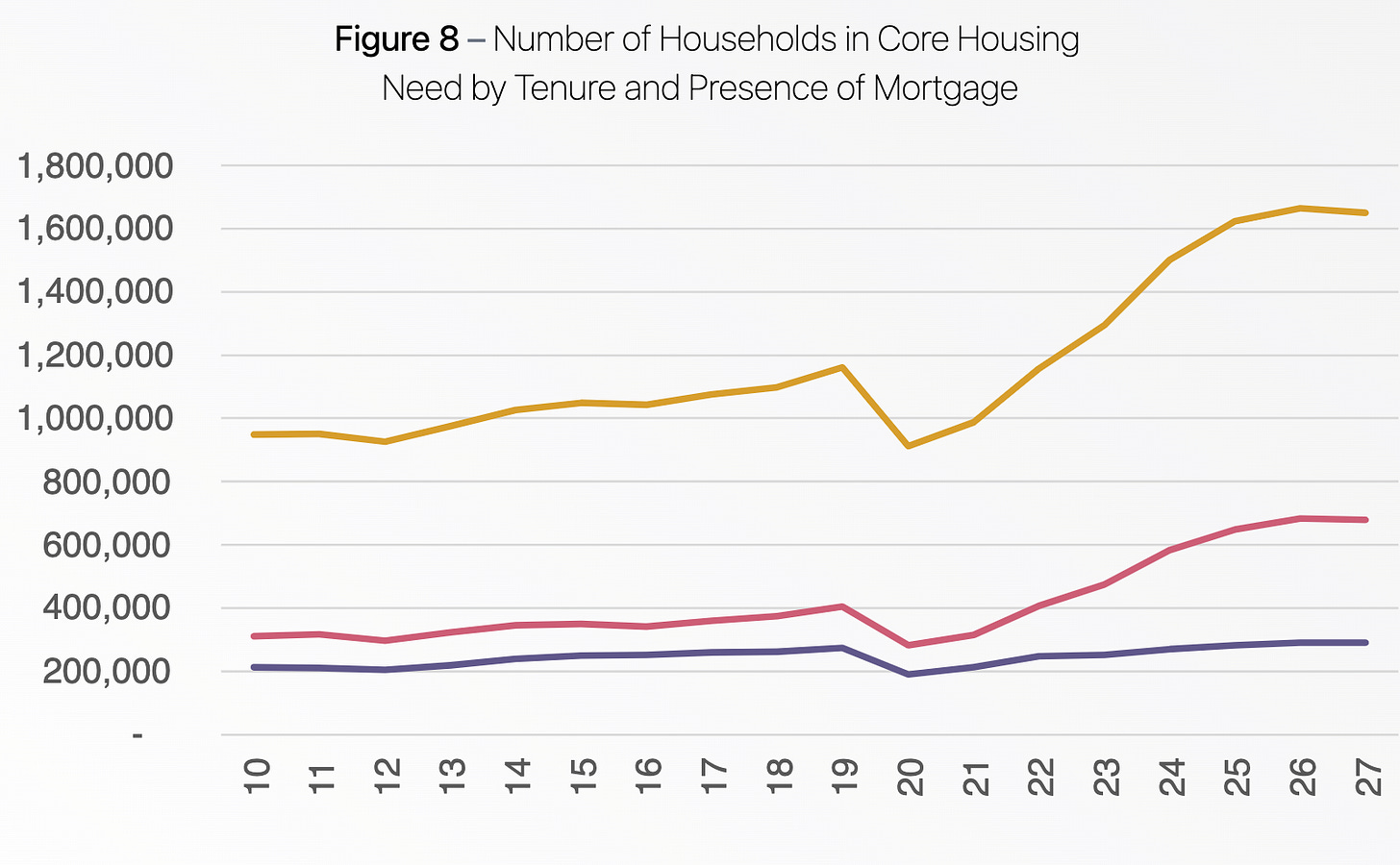

Over this time, we should have supercharged housing construction. In 2018, the Trudeau government recognized its role in this crisis and launched the National Housing Strategy. It included more than $6 billion in spending and an ambitious plan to get 530,000 households into new or refurbished homes by 2027 — a target that should have been achievable yet was, even then, insufficient.

According to the Parliamentary Budget Officer, the Strategy has been an abject failure. They project that, over that decade, Ottawa will have succeeded in getting fewer than 80,000 individuals into new homes — less than a fifth of what they promised.

When I pointed out to the former prime minister this massive discrepancy, asking him why those promised numbers didn’t come to fruition, he replied: “Well, partially, they did.” As Ottawa fiddled, the need exploded.

I doubt I need to actually brief you on any of this. Every single person in Canada is, directly or indirectly, feeling the pinch of the housing crisis. Many have become disgruntled and dejected about why we haven’t seen progress on it. Indeed, Canadians recognize the obvious: Things are getting worse.

So let’s break down the why, and look at what the parties are proposing for solutions.

Subsidizing Demand, Banning Supply

While housing construction has stayed mostly flat since 2008, the type of homes we were building slowly began to change.

For generations, most of Canada preferred detached, or semi-detached homes — front lawn, driveway for two cars, a fenced-in backyard. Montreal had triplexes, Toronto had condos, Surrey had subdivisions, but most of the new construction happening focused on the two-bedroom family homes which still rule our cities and suburbs.

This changed in the early 00s. Construction of these new homes slowed — in part because of the recession, and in part because we ran out of space to stick new sub-divisions. Construction of more efficient buildings, like duplexes and apartment blocks, rose, but not by enough to make up the loss. And not by nearly enough to meet the growing demand.

Constructing more apartment buildings and other efficient housing units was a positive sign, but it was lopsided and erratic. Ontario, for example, built 8,000 fewer apartment buildings in 2022 than it did in 2015. British Columbia’s apartment construction plateaued in 2019.

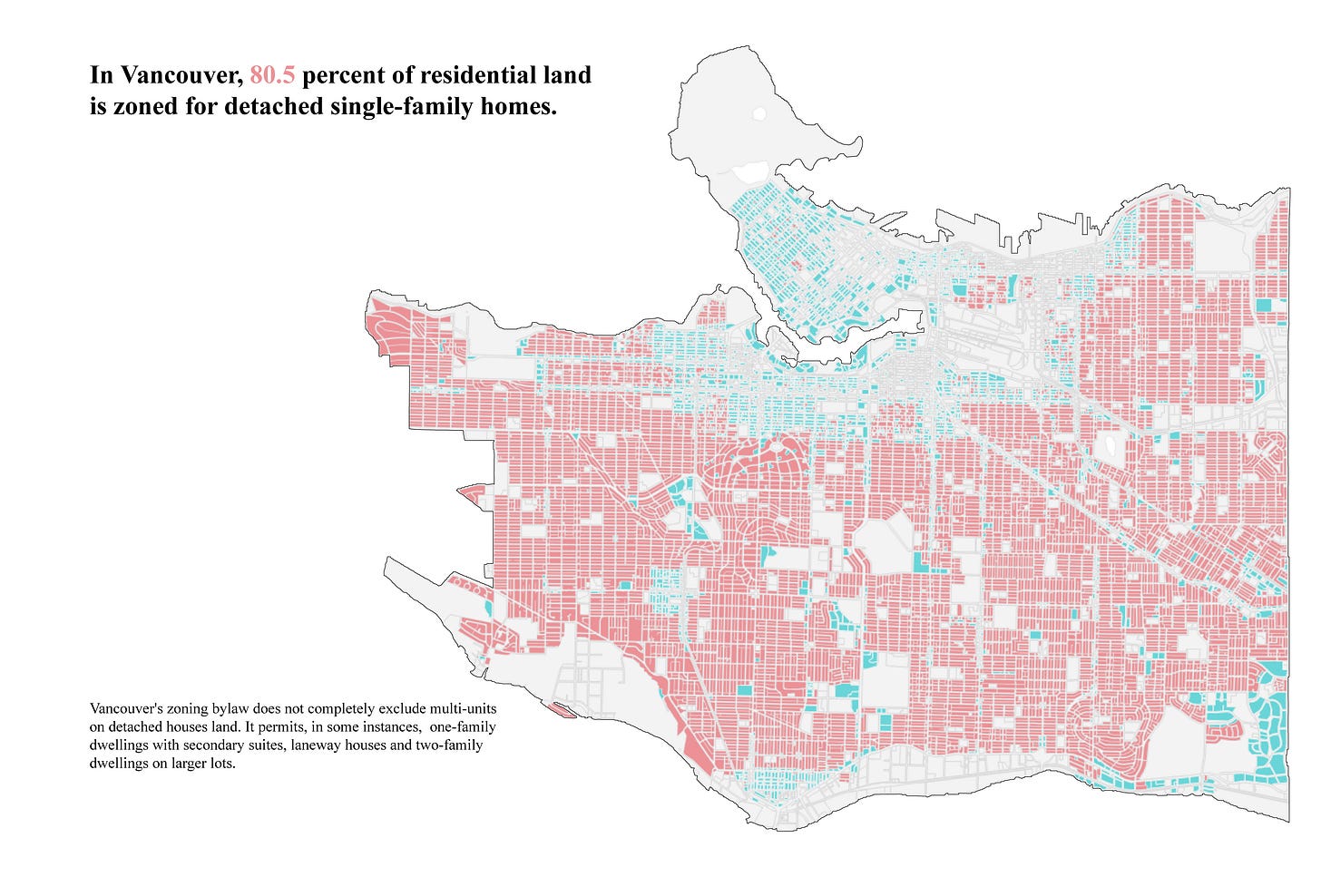

There is a simple, unavoidable reason for this: It is illegal to build useful housing in most of the country.

In those green zones — the dense urban centers, or in more permissive cities like Montreal — dozens, even hundreds, could live on each lot. But the majority of the country is made up red zones, where governments at the municipal and provincial level limit, by law, how many people could live on each plot of land. In those red zones, where only detached homes are allowed, we allowed just a few people on each lot.

Let’s just say the obvious: People in those red zones like living in red zones. They like having a front and back yard, they like having few neighbours, they like having mail delivered to their front door. And, for years, they resisted any effort to change their status quo. They voted against initiatives to ease zoning restrictions, opposed construction of new infrastructure or housing developments, and voted for politicians who wanted to create gentle growth. (See: No growth.)

So we had scarcity, we voted for scarcity, we maintained scarcity. And in that scarcity, prices rose.

That was just fine for those who already owned housing, as they watched their net worth rise steadily. It posed a minor problem for governments, as some voters began to feel anxious about the growing gap between incomes and home prices. For Ottawa, in particular, they arrived at a solution quickly: Subsidize demand.

There is the First-Time Home Buyers' Tax Credit, the First-Time Home Buyer Incentive, the Home Buyers’ Plan, and, most recently, the First Home Savings Account.

If someone took advantage of every single one of these benefits to the largest extent possible, it would free up roughly $100,000 in cash to put towards a down-payment. That may be a perfectly reasonable strategy in a world where there are ample homes but they cost too much. But in a scarce market, this is merely inflating home prices.

If you have 100 apples but 10,000 people who want to eat apples, introducing a $1,000 First Time Apple-Buyer’s Tax Credit is just going to increase the cost of apples by $1,000.

This was the status quo for years. And Ottawa was told, again and again, that their strategy was simply going to make things worse. And they continued.

Over the past few years, politicians have woken up. Well, some of them have.

The Greens and New Democrats: Nonsense Hokum

There’s not much point in talking about the NDP and Green plans, because they aren’t serious.

Both parties are hopelessly lost on this file, perpetually caught between a desire to build things and their discomfort with relying on the private sector to get them built.

This week, the NDP announced their plan to “unlock the financial power of the CMHC to offer low-interest, fixed rate and public-backed mortgages to first-time homebuyers.” Translated: Pump more liquidity into a scarce market.

The Greens, meanwhile, announced they want to “eliminate the unfair tax advantages for Real Estate Investment Trusts” and “stop corporations from buying up single family homes.” Translated: Tax capital going into the market.

Again, these initiatives may be smart in a healthy market. But they will constrain supply, drive up prices, and do little to unlock new builds. There is a way to disincentivize speculation and flipping whilst simultaneously incentivizing building. Neither party has, over the past decade, figured out how to do that.

While both parties may yet unveil stronger housing plans, expect them to promise more affordable housing without any real plan to get it built.

The Conservatives: Good, but Incomplete

No matter how you feel about the guy, Pierre Poilievre deserves credit for stabbing a shot of adrenaline into the heart of Canada’s housing policy.

In 2022, Poilievre began speaking in language which had thus far been Greek to most Canadians: Force municipalities to build more kinds of housing, and faster.

The media focused incessantly on his slightly-conspiratorial language of “gatekeepers,” instead of fixating on what he said next: "Stop blocking the poor, the working class, and our immigrants from the privilege of owning a home."

Luckily, we don’t have to guess at what this will look like: Poilievre already introduced his plan as a private member’s bill: The Building Homes Not Bureaucracy Act.

In effect, the legislation creates a test for “high-cost cities” — if they “unduly restrict or delay” housing approvals, reject building permits, or fail to liberalize zoning rules, they stand to lose billions in federal cash. Poilievre’s government would push those cities to improve their construction of new units by 15% year-over-year. Cities that succeed won’t just stave off punishment, but receive bonuses from Ottawa. The federal government would help out by removing the GST on new construction and putting federal land up on the market.

This is all good, full stop. These measures would very, very quickly increase the amount of new housing being built.

But here’s the catch: Poilievre lists those “high-cost cities” in the legislation, and they number just 22. That list does not, for example, include the on-island Montreal suburb of Mont Royale — a city which killed a massive housing development next to a luxury mall due to outcry from its rich citizens. It includes just a single city in Atlantic Canada, which is being ravaged by the housing crisis. It does not include a single municipality in Manitoba or Saskatchewan. But the list does include Montreal, which already has incredibly permissive zoning rules.

It’s not hard to figure out the commonality: Poilievre is targeting liberal cities, and protecting conservative ones.

Still, it is true that the cities targeted by Poilievre need to get their act together. But a real ambitious plan would also push suburbs, towns, and mid-sized cities — places that are not yet expensive, but which also have an abundance of space and restrictive zoning rules.

Poilievre has some other good ideas, though. His recent announcement to exempt capital gains from taxation, if the gains are re-invested into Canada — including in housing — is just plain smart economics. (I plan on writing more on this in the near future.)

Conservative plans to beef up trade school recruitment recognizes an under-appreciated factor in this mess: Because we have not built enough in recent decades, we don’t have enough people to do the building. Time to train more.

But Poilievre falls into the same trap as the Liberals: He also wants to expand government subsidy problems to slush more money into the market. Despite his constant refrain that inflation is the “worst tax of all,” he would pour billions into a home-buyer’s tax cut.

So there’s lots of good, a bit of bad, and lots of room to improve.

The Liberals: Great, but Can We Trust Them?

Pushed by Poilievre to unveil something useful, the Liberals finally unleashed their Housing Accelerator in 2023.1 The plan unveiled billions in new funding, which was directly tied to cities and provinces adopting more permissive zoning and legalizing more kinds of housing.

And, by and large, it’s been a huge hit. Cities have tripped over themselves to take the cash and upzone their cities. We have witnessed the most dramatic shift in housing legalization ever.

While some wins were easy, other governments have dragged their feet. The province of Ontario and the city of Toronto have resisted taking the bold action necessary to solve this crisis.

It has become entirely clear that more needs to be done.

To that end, Liberal leader Mark Carney has unveiled his plan to get more homes built. And, despite a few caveats, it is genuinely transformative stuff.

Released in late March, the Liberal platform basically falls under two headings: Build Canada Homes, a new government agency tasked with getting the government building stuff again; and make it easier for the private sector build homes.

Let’s start with Build Canada Homes, or BCH: A government-run home construction agency. Modelled after the WWII-era Wartime Housing Limited, the BCH would take over the construction of affordable housing straight across the country — even purchasing new land to do so. We will need to wait for the costed platform to appreciate just how many dollars in total will go into this project, but my back-of-the-napkin math suggests we’re looking at somewhere in the ballpark of $50 billion.2

As a part of this effort, BCH will invest in prefabricated home builders and place bulk orders for these homes. This promise raised some eyebrows: Prefab homes have been promised as a solution to the housing crisis for years, and yet have never come to fruition. (If you want a helpful background on the issue, I recommend this video from About Here.)

Prefab homes will never fix the entire housing crisis, but if they are well-built, well-designed, and used primarily a bridge to help those in precarious housing situations, they have the potential to be the quickest-impact and lowest-cost path out of our current chaos. But this will also require strong-arming cities into allowing them.

As I understand the policy, the Liberals seem to well understand the helpful role that prefab homes can play without betting the farm on them. Good.

The BCH will also provide $10 billion to home builders in immediately accessible capital for affordable homes, in particular for student residences and seniors’ homes.

Onto the private sector side: Carney says he would keep, and expand, the Housing Accelerator, and expand its aim to speed up government approvals — not just expand zoning. The devil will be in the details of how that looks in reality, but it has the potential to energize the program further.

Carney would also bring back the long-forgotten Multiple Unit Rental Building (MURB) tax incentive. This is an interesting one.

The MURB program, which ran from 1974 to 1981, was essentially a tax shelter for those who built or bought apartment buildings. It allowed owners of these buildings to write off a slew of capital costs from their income taxes, including many ‘soft’ costs (such as property taxes.) Simply put: It made apartment buildings better investments than other types of real estate.

The program was particularly studied in relation to its effect on the Vancouver market. The ‘steel man’ case for the program is that it quickly moved investment capital from condos towards apartment buildings, which have suffered by being less attractive to investors. (Except predatory low-margin investors.)

Not everyone agrees. One researcher at the time contended that the MURB program “was not effective in achieving its objective” and that the real effect of the program was to “create windfall gains for existing owners of multiple family zoned land at the time the legislation was passed.”3 (Worth noting that part of this argument turned on the idea that apartment rentals were banned in much of the city, which unfairly distorted the market.

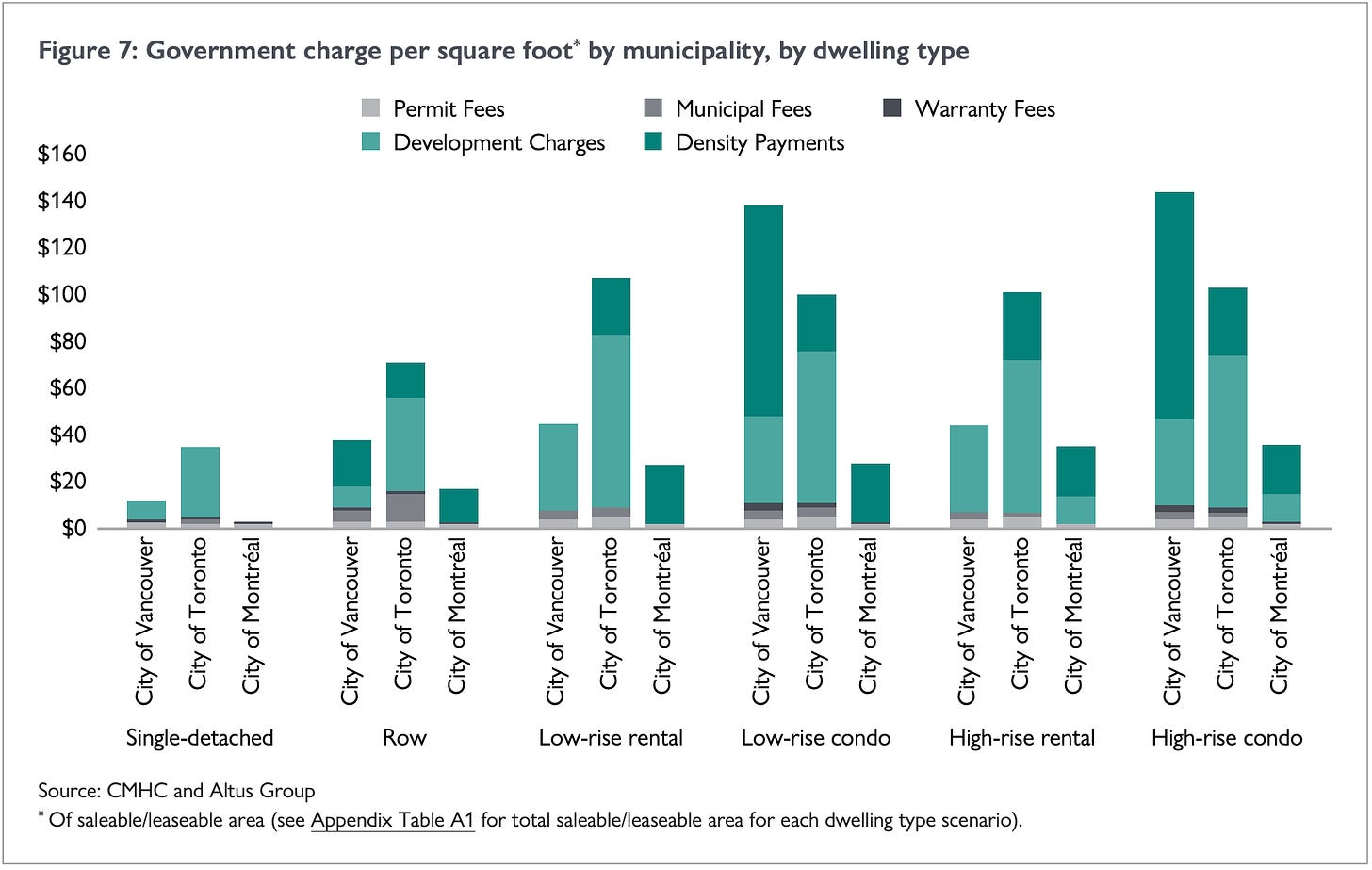

And onto the last piece: Carney proposes cutting municipal-level development charges in half for multi-unit residential housing, with the federal government stepping in to replace any lost income to the cities, for five years.

This is controversial, for a few reasons.

Development charges are generally popular with citizens, because they soak those evil developers and force them to fund the externalities of their new construction — they build sidewalks and transit for the new citizens who will live in these buildings, for example. But development charges have also become a vehicle for some cities to make their budgets work without raising property taxes. I’m looking at you, Toronto.

This has created perverse incentives. Because it is so expensive to build rental buildings and condos in Toronto, they disproportionately become luxury buildings or are built poorly by developers looking to turn profit. Reducing development charges — and shifting the tax burden to homeowners, particularly those who have seen multifold increases in their net worth thanks to skyrocketing property values — is the way to flip those incentives. The CMHC estimates that, without development charges, the total cost to build apartment buildings would fall by about 15%.

But does that mean the federal government should step in and fund this cut in charges?

That’s where this gets squishy. Toronto raised about $518 million from development charges in 2024: We can estimate that roughly half that amount came from charges from multi-unit residential. That means the Government of Canada is providing about $650 million to Toronto over five years to maintain the unsustainable status quo.

Cities with reasonable development charges, like Montreal, will get just a fraction of that money.

So, yes, Carney’s proposal is manifestly unfair. But the simple fact is that the whole country is suffering because of Toronto’s intransigence. The housing crises in Montreal, Halifax, Moncton, and elsewhere were driven, largely, by an influx of new residents fleeing cities with housing scarcity. And this development charge subsidy is something that can be done immediately, with relatively little squealing from Toronto’s or Vancouver’s politicians.

Still, it feels like the Liberals have consistently opted for carrots when a stick would be a better tool.

More fundamentally, the question remains: Why didn’t the Liberals do any of this in 2015?

Where Does That Leave Us?

Between the two parties most likely to form government, we have two solid — and very different — plans.

In my ideal world, we would combine them. Take the Liberals’ plan to get the government building again, and the Conservatives’ hard-nose approach to making the cities and provinces get in shape.

Unfortunately, it seems that each man’s need to distinguish himself from the other has entrenched the parties into worse territory.

“You'll own nothing and be happy,” Poilievre told the crowd in Kingston on Wednesday night, a wink at the bug-eyed WEF conspiracy theories that he loves so dearly. “So if you elect the Liberals, the hope is that, one day, they'll make you a tiny prefab home with no parking space that they will own and you will rent from the government. Does that sound like a bright future to you?” (The crowd seemed slightly confused by this tangent.)

As with so many things, Poilievre’s culture war lens is stopping him from seeing good policy right in front of him.

It ignores the fact that parking requirements are a massive hinderance to building denser housing. We should be building more homes without driveways.

The Liberals, meanwhile, have just an abysmal track record on housing construction. Tapping Nathaniel Erskine-Smith to be housing minister signalled a substantial change in direction, although I do worry that the Liberals’ build-build-build mantra is being diluted by their willingness to stand-up programs and cooperate with intransigent governments which send the message: No-no-no.

The only thing to do now is to absolutely grill your local candidates on how they will, personally — not as a party — advocate for strong solutions to the housing crisis.

We got into this mess because of endemic buck-passing and the ability for a small group of anti-development yahoos to hijack the conversation. The only way out of this is to demand accountability and make it clear that we want more homes.

That’s it for this (longer-than-expected) dispatch.

Expect more of them in your inbox in the coming days, as I try and break the logjam of writing that’s built up over the past week.

I’ll be joining Mark Leon Goldberg for a chat about Canadian politics at 2:30pm EST today, so tune in for that!

Over at the Star, I’ve got a column about the desperate need for RCMP reform and some jeers for our leaders who have been weak in standing up for Greenland. In the next few days, I’ll have a write-up of my sit-down with Green Party co-leader Jonathan Pedneault — Chaos Campaign subscribers will be getting the full transcript and audio. Stay tuned!

The Liberals had previewed some kind of housing accelerator plan in their 2021 platform, but they seemed to be in no rush to actually do it — until Poilievre’s plan started finding purchase in the public.

This is some quick and dirty math, assuming Carney takes aim at the Canada Housing Infrastructure Fund ($6b), the Apartment Construction Loan Program ($15b), the Canada Rental Protection Fund ($1.5b), Apartment Construction Loan Program ($40b). As you can see, $50 billion is probably a conservative estimate.

An analysis of the effects of M.U.R.B. legislation on Vancouver’s rental housing market, by Anne Patricia Wicks (University of British Columbia, 1982)

Justin, one issue I'm not sure anyone is looking at is the mismatch of what is actually being built versus needs.

In particular, builders of condos and apartments seem stuck in the idea that only young childless singles/couples and empty-nesters want to live in condos and apartments. So condos and apartments are nearly all bachelor, one, and two bedroom. Meanwhile, the actual demand for 3 and 4 bedroom condos and apartments is completely neglected.

I've read reports of even Toronto having a glut of small apartments, while the market for larger dwellings is screaming.

Do you see any of the plans on offer having any impact on this failure of the market?

Great article. I’m looking forward to the Libs and the Cons trying to outdo each other by making their housing plans better.

One thing in your article that is misleading is that you say Vancouver is zoned 80% single family. That’s no longer true. The BC NDP has changed zoning rules throughout the province to allow 4-plexes (and 6-plexes in some places) throughout all municipalities.

The BC NDP have some great housing plans. I hope they work out.