Welcome to the New Hyper-Normalization

The raid on Mar-a-Lago means war. Plus: The man behind Ottawa's mysterious convoy church. And: How do people really feel about Alex Jones?

Over his nearly two decades as General Secretary of the Soviet Union, Leonid Brezhnev became a decorated man: The Lenin Peace Prize, the Lenin Prize for Literature, and, no fewer than a half dozen times, the Order of Lenin.

For each new medal affixed to his breast, the thousands of carbon copies of the premier had to be updated to match. "Every time Brezhnev was awarded a new order I had to make sure that my district artists, working overnight, added that order on all his portraits in the district,” a local party official explained.

Alexei Yurchak, in his in 2006 book Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More. wrote: "Even though the presence of an additional medal on Brezhnev's suit was publicly known, this fact was symbolically represented in terms of immutability rather than change, which was an example of the hypernormalization of this authoritative symbol.”

The medal had always been there, in other words, and there was no use arguing about it.

Yurachak’s book dismantled the neatly-packaged, and generally accepted, idea that the Soviet Union existed for as long as it did because it was totalitarian — end of story.

His idea of hypernormalization explained how the Kremlin managed the chaotic unwinding of their late socialist empire explicitly with the help of the people. As things became unglued, the Politburo merely asserted the chaos as normal. Citizens, meanwhile, accepted this normalization and contributed to it. It’s why the fall of the USSR came as such a shock to many in the Eastern Block: They had deluded themselves into thinking things were going according to plan.

The frogs weren’t just sitting in a pot of warming water, they were convincing each other the temperature remained the same.

The concept was borrowed by British filmmaker Adam Curtis for the title of his 2016 documentary. Curtis transports the idea from east to west — replacing nightly touch-ups for Brezhnev’s portrait for the mind control of social media; revolutionary songs for pop culture; imagined counter-revloutionary plots for the fear of Islamic terrorism; and so on.

For decades, this hypernormalization has been all about protecting state authority: When France wouldn’t bomb Iraq, we came together to serve ‘Freedom Fries’; when calls mounted for police accountability in the murder of Black men, we chanted ‘Blue Lives Matter’; when the Obama White House expanded an unlawful drone program, we obsessed over his tan suit. Things that became unimaginable decades prior suddenly seemed like facts of life.

But like all of Curtis’ work (including last year’s fantastic Can't Get You Out of My Head) it’s an intoxicating story that is always a bit too tidy. For those unfamiliar with Curtis’ work, his theory goes essentially like this: The complexity and chaos of the last half-century drove unprecedented anxiety, which pushed society to retreat inwards into a form of intense individualism. Elites weaponized that paranoia to amass more power.

Curtis’ thesis isn’t wrong, per se, but it’s a bit too neat and tidy. He, for example, tries to paint Donald Trump as the culmination of this trend.

But Trump doesn’t fit into this idea of hypernormalization. He came in to smash the ailing liberal consensus, not continue it.

For all his faults, Trump pointed to the painting of Brezhnev and said: He didn’t have that medal yesterday! He chided an interventionist foreign policy, lambasted an economy where the rich get bailed out first, and mocked a media establishment that preserved the orthodoxy. All those paradoxes suddenly seemed so clear to his fans. In so doing, a massive number of people bolted up in their chairs and went: He’s right, this isn’t normal. In turn, Trump got to define what normal is. And his supporters were deputized to confront this age of anxiety, not shy away from it.

It was white nationalists who originally pitched the idea of banning Muslims from America. Then it was picked up by hard-right figures like radio host Michael Savage. Soon, it was installed into the heart of the Trump machine. Then it became a rallying cry for millions of people who had been told for two decades that Muslims were the reason for their fears.

Initially, we were told the travel ban was a racist pipe dream, something that could never happen. Then it happened. Then it was challenged, challenged again, abandoned, reintroduced: Some form of the Muslim ban stayed in effect for the majority of the Trump presidency. The White House expanded the travel ban in 2020, to muted reaction. It had become normal.

The Trump ecosystem has an incredible power to normalize. Over the last five years, his base of supporters have normalized the existence of a conspiracy cult that believes Hilary Clinton is complicit in ritual child sacrifice; the idea that bearing arms is not just a right, but that there is a genuine duty to be outfitted with high-power assault rifles; that a naturally-occuring virus was the handiwork of the very public health official trying to protect people from it; and that a national election was rigged by a conspiracy involving the media, election officials, Republicans, Democrats, and China.

This is hypernormalization the likes of which the Soviets only dreamed of. Every new piece of data is covered in mortar and added to the wall surrounding the reality they’ve built for themselves. For every notion or conspiracy theory held out by the former president and his lackeys, the mob returns five back. When Trump issued a forcefully vague appeal to have his supporters march to the Capitol and give “courage” to Mike Pence (the past never had been altered. MAGA was at war with Mike Pence) they met that call, and then some. When a sliver of humanity emerged in the hours after the assault on the Capitol, in genuine horror at the attempted coup, it was quickly smothered. Soon, it was normalized: The FBI did it; it was Antifa agitators; it was totally peaceful; violence is necessary to fight fraud; we should hang Mike Pence. Take your pick.

Even if the rest of society is struggling to make sure these obscene acts never become normal, it is a fight against a rising tide.

Which brings me to the point of this week’s newsletter [chorus: about time!]: The raid on Mar-a-Lago.

Anyone following the mounting proceedings against Trump knew it was a matter of time before a search warrant was executed. Beyond the increasingly-strong case being made at the January 6 committee, Trump is also facing lawsuits or investigations from E. Jean Carroll, Mary Trump, Michael Cohen, no fewer than seven representatives and police over the January 6 insurrection, the NAACP under the Ku Klux Klan Act, the New York Attorney General for possible real estate fraud, six protesters who claim they were assaulted by Trump’s security detail, Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg over possible tax evasion, the D.C. Attorney General over incitement at the capitol, the Fulton County District Attorney over unfair election influence, and, well, others.

If it wasn’t the Department of Justice, acting on behalf of the National Archives to preserve classified materials thought to be sitting at Trump’s mansion, it could have easily been another legal imbroglio the former president found himself in.

No matter the reason — and nevermind that the Department of Justice had already subpoenaed the former president for the records in question — the fury that erupted from the MAGA camp after the raid was perhaps even more intense than we could have expected.

Multiple right-wing figures, from Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene to streamer Steven Crowder, called the raid an act of “war.” Calls began mounting to disband the FBI, and to launch investigations of Attorney General Merrick Garland once Republicans take back control of government.

Those calls to war inspired Ricky Shiffer, a 42-year-old electrician in Cincinnati, to attack the local FBI headquarters.

After announcing his “call to arms” Tuesday, a user asked Shiffer if he was “proposing terrorism?” Shiffer’s account replied, “No, I am proposing war.”

“Be ready to kill the enemy, not mass shootings where leftists go, not lighting busses on fire with transexuals in them, not finding people with lefist signs in their yards and beating them up,” the post said. “Violence is not (all) terrorism. Kill the F.B.I. on sight, and be ready to take down other active enemies of the people and those who try to prevent you from doing it.”

We are seeing the hypernormalization of extremism, fascism, and even terrorism on the American far right. While it’s not the first time, it’s certainly the first time that a major political party has entertained it as legitimate.

It’s not getting better.

Meanwhile, in Ottawa, anxieties are still running high as a mysterious pro-”freedom convoy” group sets down roots in a deconsecrated church.

As I wrote in dispatch #11, a group calling itself The United People of Canada recently announced they would be setting up shop at Saint Brigid’s Church, an imposing and long-closed church in Ottawa’s ByWard Market.

The directors of the organization have, to varying degrees, ties to the anti-vaccine trucker convoy that occupied Ottawa for three weeks earlier this year. But they do not, as I wrote, appear to be part of the quasi-official plan set up to channel the convoy’s energy into new projects. (Those ‘official’ plans, largely run through Veterans4Freedom, appear to be largely stalled.)

Since I first wrote about them in mid-July, the organization has consistently been in the headlines. They’ve insisted that while they are “freedom fighters,” their goal is to open a cafe and community center for “freedom fighters” and non-”freedom fighters” alike. They’ve called their new headquarters an “embassy” that will help repair the “divide” in society. They’ve insisted they are in “a due diligence process” and that the building is under a “contract of purchase and sale agreement." Most recently, they’re promising to set up a “private security force” to defend their “embassy” from vandals. (Forgive the excessive scare quotes.)

Let’s talk for a second about how serious this organization actually is. First off: The church is still listed for sale, still for a shade under $6 million. (Plus around $40,000 per year in property taxes.)

The man leading this supposed effort to buy the church is William Komer, head of Campus Creative — a London, Ontario-based design and consulting business.

Very little about the company screams “has $6 million to spend on a church.”

It was first incorporated in 2013, but dissolved two years later after failing to file its annual returns. The incorporation address was a very stately home in London that appears to belong to Komer. (Similar homes in the neighborhood go for around $800,000, so he’s not without means.) Campus Creative was reincorporated in 2016 (minus one of its directors) this time listing its address as an office in a small building owned by St Peter’s Cathedral Basilica.

Campus Creative lists no fewer than 13 locations across Canada. His other business, Synesure Inc, lists the same London address and an unspecified location in Vancouver. Those various addresses are also listed as studios operated by wedding photography company Under the Umbrella — also owned by Komer.

All of those addresses, apart from Campus Creative’s London office and Under the Umbrella’s Toronto studio, correspond to coworking spaces. Some, like their address in Kingston, are coworking spaces that happen to be in deconsecrated churches. (Notice a trend?)

Komer is also the director of a video game company that seems geared towards operating in the Metaverse, and a handful of other corporations that don’t appear to be doing much.

Despite being rather prolific, Komer’s actual operations seem pretty modest: All of his various enterprises seem to have somewhere between a half dozen and a dozen employees between them. (Many employees seem to work for multiple companies.)

Komer is a master in bluster.

In 2012, Komer submitted plans to take over a vacant building in London and create the “London Technology Development Centre” — but the site was already slated for redevelopment by the YMCA. Komer asked city council to punt the YMCA to another site, and to help secure $9 million in government funding for his half-baked idea. London City Council denied the request, but offered to help Komer find another site. Nothing came of it.

One person familiar with Komer’s work in London points to the failed technology centre, saying that the Ottawa “embassy” is more likely the same ol’ story — a “PR stunt” designed to gin up donations.

That’s a pretty good guess, I reckon. Komer told The Ottawa Citizen that a local financial advisor was contributing a “sizeable” amount of money for their acquisition of the church, but a week earlier he told the CBC that the plan was to finance the sale through “community bonds.” (See: Donations from rubes.) All this screams: He doesn’t have the money, but he’ll fake it ‘til he makes it.

What exactly Komer’s endgame, here, is a bit muddled. He’s obviously not keen to share his plans with the media — instead, proffering some vague platitudes about togetherness and unity.

The group’s repeated insistence that it is not explicitly a front for the anti-vaccine convoy types, however, is falling away pretty fast. On top of some sparsely-attended weekend BBQs, the group has also been holding something called “The Freedom Convoy: a Community Conversation Drop-in Casual Community,“ which I gather is daily conversations about the convoy, done casually. For the cmmunity.

The events, however, are “sponsored” by a group called Vaccine Injury Awareness — which encourages people to report side effects from the vaccine, and hosts an incredibly slanted survey that basically forces respondents to say they were cajoled into getting the vaccine. It also appears to belong to Komer: Their website was designed by Komer’s company Synesure and is registered to Campus Creative’s London address.

The United People of Canada is also hosting “Open Mike” with Brian Derksen, “The Trucker That Never Left.” Derksen has been sitting outside the gates of Parliament throughout the spring and summer, protesting vaccines. He written long screeds borrowed directly from sovereign citizen nonsense legalese — “under the current system we are all being tried and convicted through Maritime admiralty this law does not apply to us we are under common law God's law,” and so on. He’s called for the Governor General to remove the government in protest of the vaccine mandates. He is, in short, a bit kooky.

The United People of Canada have insisted that anyone is invited to come speak. Multiple comments on their Facebook suggest that is not the case.

The group is also being actively promoted by WarCampaign, a popular pro-convoy Youtube account run by comic artist Ro Kabir Kumar a.k.a Rohan Kumar Pall, who had been involved with Comicsgate — a campaign that opposed women and diversity in comic books. Nowadays, his shtick is sharing bug-eyed conspiracy theories, doing anti-LGBTQ rants, and promoting the anti-vaccine cause.

All to say, this continues to look like a harebrained scheme to try and create a foothold for the “freedom” cause in downtown in Ottawa, but given the meagre enthousiasm for the affair, it seems unlikely they will be able to fundraise the significant amount of cash needed to keep the grift going.

Below the paywall: How do people really feel about Alex Jones and QAnon? Some interesting new polling data offers some clues.

I’m not a huge fan of polling on conspiracy theories: If you ask people about something they have never heard of, I figure they’re likely to just pick a random answer instead of pressing 3 for “don’t know.”

I suspect that if you call 2,000 people and ask “are cats boys, and dogs girls?” about 10% will say yes.

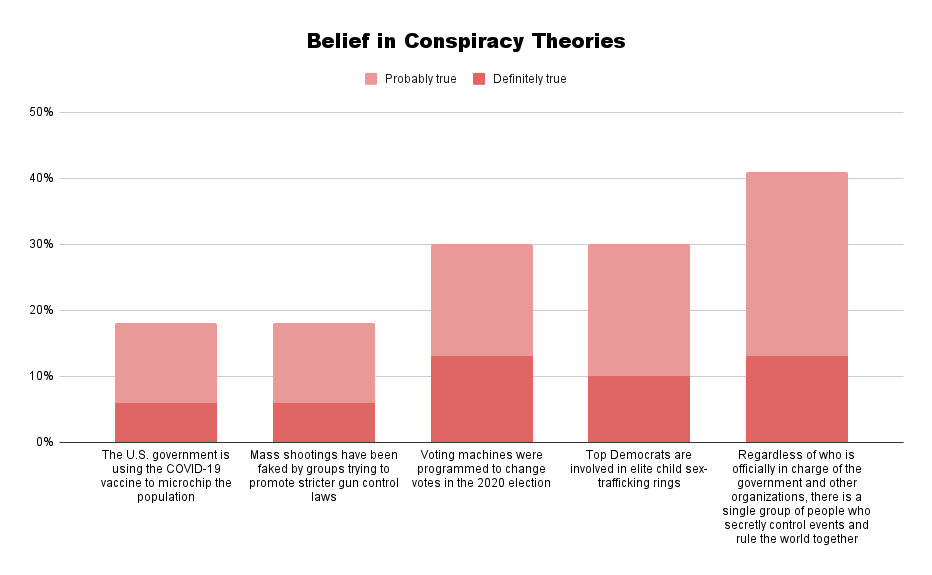

Polling around QAnon, for example, has been all over the place: Rocketing from the low single figures to as high as 22% in some polls. Individual tenets of the conspiracy cult poll even higher, suggesting that people may identify with the movement without using the name.

But sometimes, polling can be useful in what it doesn’t show.

A new packet of data from YouGov, for The Economist, has some interesting insights into Alex Jones’ conspiracy movement.

The pollster asked a representative sample of Americans about their feelings on the Infowars founder just as his defamation trial was blowing up. Somewhat surprisingly, nearly 40% of respondents said they didn’t know how to feel about Jones. More than a third said they had a very unfavourable view of the crank, while around 17% had a very or somewhat positive impression.

That is roughly where I would have pegged public perception of Jones as of last year. The poll also found about 70% of people had heard something about his defamation case, meaning they’re not entirely unaware of the man. This poll definitely suggests that people aren’t buying his underdog shtick, and that his growth potential is somewhat limited.

Jones’ numbers, of course, go up in some demographics: Nearly a quarter of white men with no college education have a positive impression of Jones. Overall, though, Jones’ unpopularity is fairly constant.

Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Jones acolyte, polls somewhat better: Nearly one-in-four Americans have a positive view of the QAnon-affiliated congresswoman.

To give you a bit of a baseline for this scale: Asked about QAnon, just 12% had a favourable view. 40% didn’t know.

This kind of polling probably can’t actually tell us how many people follow a given conspiracy movement, but it can absolutely track trends. YouGov asked the same question about child sex trafficking in October 2020 — back then, 25% said they believed the party brass were involved. So, a minor increase. It found a similar level of favourability for QAnon, however.

All told, this isn’t good news, but it’s not an alarm bell, either. It seems like the prevalence and reach of these conspiracy theories may have reached their apex. More troubling, of course, is that these conspiracy movements have infected broader American and international conspiracy politics. QAnon and the anti-vaccine movement are, in essence, think tanks for the broader right-wing movement.

Neat and tidy theories can be accurate as far as they go but are rarely complete. The real world, unlike fiction, faces no public pressure to make sense to everyone.

(Thank you for getting to the bottom of the effort to buy St. Brigid's. Just another bullshit artist with pretensions.)