Webster’s dictionary defines 'recrudescence’ as “increased severity of a disease after a remission.”

I open this week’s newsletter with Webster’s dictionary defines because I don’t know how else to start talking about where we’re at right now.

It’s been just over a week since 75 million Americans turned out to elect Donald Trump as the 47th President of the United States of America. If you’re anything like me, after waking up bleary-eyed and slightly queasy, you proceeded to read a disquieting pile of analyses about how, why, and what next. Or, perhaps, you’ve avoided all this weaponized introspection for your own sanity.

Either way, I thank you for opening this one.

Over the past week, inbetween chewing on pens like a beaver at tree bark and nervously pacing holes in the floor, I’ve been trying to figure out my own meta-theory of the election.

I spent election night in Washington, D.C, listening to a Republican data guru crunch numbers as he became more and more gobsmacked by the returns. Look at Miami-Dade! Look at Hamilton county! My god, he’s closing the gap in New Jersey. It became clear that whatever optimism we had huffed in recent weeks had gotten us delusional and high.

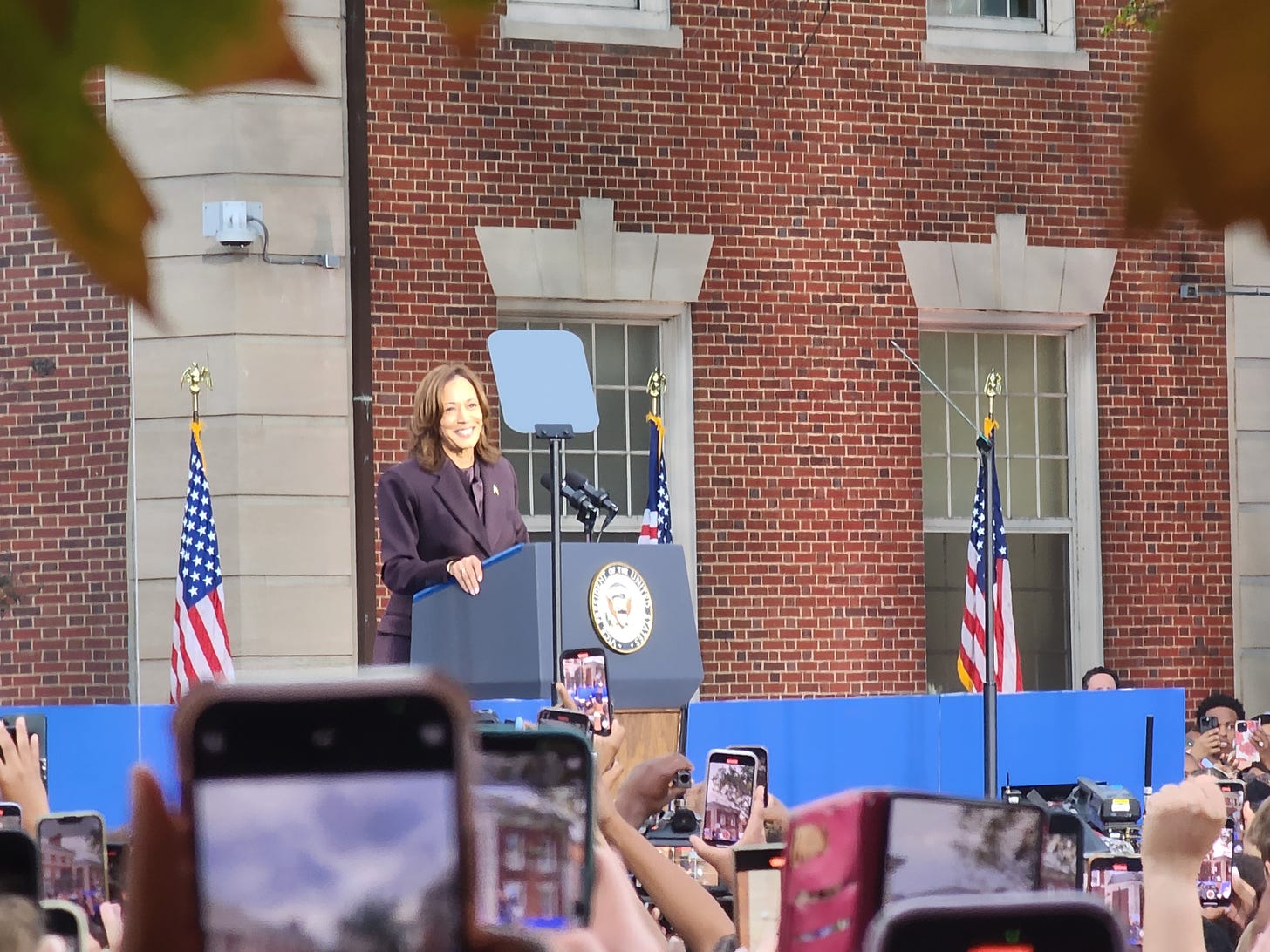

The day after, with no contested election to cover, I wandered into Kamala Harris’ concessions speech.

“A fundamental principle of American democracy is that when we lose an election, we accept the results,” she told her assembly of shell-shocked supporters. “That principle, as much as any other, distinguishes democracy from monarchy or tyranny. And anyone who seeks the public trust must honor it.”

As with everything in our current age, last Tuesday’s election prompted all kinds of scalding hot takers and knee-jerk reactions. But it has also unleashed a pretty fascinating amount of introspection and soul-searching about the state of liberalism, the promise of progressivism, and the threat of fascism. These are lessons that need to be learned by liberals, leftists, and establishment types everywhere: In Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom, and in the entire industrialized world.

The benefit of delivering this dispatch a full week after the results were declared is that I can take stock of all the good analysis, sloppy takes, smart criticisms, and dumbass scapegoating. I am, essentially, cheating. Just the same, you’ll see references to those other analyses, good and bad, absolutely littered throughout this dispatch.

So this week, on a very special Bug-eyed and Shameless, I want to dig into the current state of the information war: The return of Trump, why the Democrats lost, what working class people even want anymore, why men are so mad, the ecosystems where MAGA thrives, and how to unbreak the media. Here we go again.

On Learning the Wrong Lessons

Let’s just dispatch with lots of bullshit really quickly.

No, woke is not broke. There are no electoral victories to be found by adopting the reactionaries’ framing of civil and human rights. Sacrificing the needs of one voter for the vibes of another is a very, very bad idea. Just listen to Jon Stewart.

No, defending the rights and dignity of trans people did not cost the Democrats the election. Harris rarely mentioned LGBTQ issues in her campaign and polls show Trump’s anti-trans rhetoric didn’t have much of an impact. Just look at pro-LGBTQ Andy Beshear, who won re-election in deep-red Kentucky. There is, again, no glory to be gained in shrinking the coalition and abandoning the targets of Trump’s ire. As Julia Serano eloquently put it: “What message does it send to them if Democrats reject us?”

No, the Democrats did not lose because they did too little to punish migrants.

No, the Democrats didn’t lose because they got too many celebrity endorsements. (Though it didn’t help.)

No, the Democrats didn’t lose because they refused to get tougher on Israel. (Though, again: It didn’t help.)

No, the election was not unwinnable for Democrats. No, Elon Musk didn’t use Starlink to rig the election. (Come on.) No, Russian meddling did not change the outcome of the election.

Had the Democrats lost by a narrow sliver, or if their collapse had been isolated to a specific region or sub-population, I think you could easily come up with some simple explanations. But the fact is that millions of Democrat-leaning voters stayed home, millions of undecideds and independents broke for the Republicans, and millions of non-voters turned out for Trump. These voters were, per the exit polls, working class. And while Trump still didn’t win a majority of young men, Latino voters, or Black men: He did improve his standing in each constituency.

Some have grasped at straws, insisting that Harris didn’t do that badly, considering everything. Those people need to have their optimism beaten out of them. (Metaphorically)

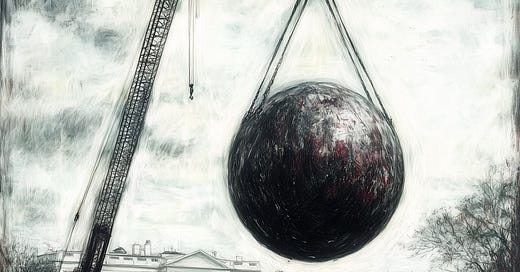

Because of Harris’ loss, Trump is now returning to the White House with a more radical agenda than he had eight years ago and a clearer mandate. He is no accidental president, nor a president chosen because the other option was unpalatable. He is clearly what Americans want right now, and Democrats fundamentally failed at putting up a better option.

At the same time, Trump’s brand of reactionary paranoid populism has proven successful everywhere. The Democratic Party is not a singularly incompetent, corrupt, or out-of-touch political force. While it may set the tone for an international coalition of liberals and progressives, it is essential to note that this is a global problem with regional particulars. So it is not the case that the Democratic Party, and only the Democratic Party needs fixing. This isn’t about one party and its personalities, it is about the various inputs, constituencies, ideas, strategies, organizations, movements, and conversations that need top-to-bottom reform.

There is already an enormous amount of navel-gazing about how the Democrats can renovate themselves into something that is, superficially, better. That’s a dead end. If you ask me, it’s high time the Democratic Party splinter into smaller parties, designed to generate different ideas and policies — but still capable of endorsing the same candidates for office. (There is some precedent for this.) But I’m not even allowed to vote in America, so you don’t need to listen to my crackpot ideas about multi-party democracy.

Instead, this is a grab-bag of ideas of how genuine self-improvement of a broad spectrum of politics might look in the years to come.

On the Need for A “Left-Wing Joe Rogan”

“Not to be grandiose, folks,” Al Franken began. “You and I know that the radical right wing of the Republican Party has taken over not just the White House, the Congress and, increasingly, the courts — but even, and perhaps most insidiously, the airways.”

But that was over, he continued. His first show on the Air America network would be both “an ending and beginning,” he promised. “An end to the right-wing dominance of talk radio, the beginning of a battle for truth, a battle for justice, a battle indeed for America itself.”

This was 2004. Air America had assembled a roster of known voices to create a talk radio station which would finally compete with this right-wing chorus. Now the liberals would reach through the airwaves and reach the commuters, truckers, and shift workers. Franken, joined by Janeane Garofalo, Chuck D, and Marc Maron, was set to become the anti-Rush Limbaugh. With one of the most consequential elections in American history looming on the horizon, it could not have come soon enough.

Limbaugh helped deliver Republican victory in the ‘94 midterms, the ‘00 presidential election, and his network of copycats had helped build the case for the ‘03 Iraq war. But that was all over, Franken said, Air America was here.

He was wrong: Air America bombed. Bush, we know, won an even bigger majority in 2004 and Republicans kept both houses. Air America’s ratings were poor and its finances were worse. The network hadn’t just failed to turn the tides of neo-conservatism, it couldn’t even win over liberals.

Air America technically limped along for another six years, but it was dead on arrival. Some of its talent, like Rachel Maddow, went on to bigger and better things. Others, like Robert F. Kennedy Jr, went on to much worse things. One of its hosts, the hilariously pugnacious Randi Rhodes, managed to briefly beat Limbaugh in the ratings — probably because she was the only one who sounded like Limbaugh. But Air America was, in general, a bust.

Right-wing blowhard Bill O’Reilly gave a pretty apt assessment of the network: “Tedious.” The Air America hosts were eggheads, trying to replicate Limbaugh’s success without doing the nasty things that made him so successful. They were committed to nuance, facts, fairness, transparency, and some semblance of journalistic ethics. Those are all perfectly wonderful and moral things, but that’s not what talk radio was. They were trying to serve local, organic, fair trade, gluten-free McDonald’s with a side of alcohol-free tequila.

As Limbaugh himself noted, the whole thing smacked of condescension: “Nobody thinks conservatives have a brain. They think that they can just pluck some liberal out of the sky and put him on the radio and create a bunch of liberal mind-numbed robots.”1

Visiting the grave of Air America might be a useful practise for those calling for a new “left-wing Joe Rogan.”

It’s pretty undeniable now that the Joe Rogan Experience was instrumental in Trump’s bruising victory. But, despite the simple media narratives, it wasn’t just Rogan: It was also a dizzying network of streamers, podcasters, and commentators who you’ve probably never heard of. They talk about betting, crypto, wellness, technology, sports, comedy — and Trump. It is an inter-connected and symbiotic ecosystem which goes well beyond one man.

As influence economy hagiographer Taylor Lorenz writes:

The conservative media landscape in the United States is exceptionally well-funded, meticulously constructed, and highly coordinated. Wealthy donors, PACs, and corporations with a vested interest in preserving or expanding conservative policies strategically invest in right-wing media channels and up and coming content creators.

It would be nice, certainly, if someone came along and poured money into a competing economy which values truth, tolerance, and all sorts of high-falutin’ ideas. But such an endeavour would likely end up a money pit like Air America. Much in the same way liberals didn’t actually want to listen to talk radio — nor did they really want to produce it — maybe copying Trump’s loyal media network isn’t such a great idea.

Better, I think, to look at why Rogan is popular. Because his secret is not, by any means, money.

For starters, Rogan is long-form. His interviews regularly stretch into three hours. (The same length, I would note, as Limbaugh’s shows.) That length allows the show to visit a variety of topics and go deep into a few ideas. It is an anathema for talking points or canned speeches. His selection of guests is often surprising, unexpected, and unorthodox. Most are not political, many are fringe and quirky, lots are heretical in their thinking. The show is a great place, for example, to hear up-and-coming standup comedians. Rogan’s media juggernaut, at its core, assumes its listeners are smart, engaged, curious, politically un-aligned, and distrustful of those who forbid certain strains of thought.

Now, I think Rogan is a horrendous interviewer, an unbelievably naive rube, and a customer for genuinely stupid ideas. (Dispatch #59) But it’s hard to ignore that his show has a remarkably broad appeal to people of all political persuasion.

One of the worst parts about liberal-y podcasting is that it is often easily categorized. Pod Save America: A show for Democrats. Chapo Trap House: A show for dirtbag progressives. Behind the Bastards: A show for left-wing history nerds. Call Her Daddy: A show for modern feminists.

Where is the show that is as wide and weird as the Joe Rogan Experience? Which shows offers leftism and liberalism for people who might not be leftists and liberals?

Who on the left is engaging young people in philosophical jousting like Jordan B. Peterson is? Which progressive is issuing online calls-to-arm like Chris Rufo? Who is producing edgelord Borat-esque comedy like Matt Walsh?

These characters are loathsome. But it is inescapable that they have tapped into a segment of the market that has reached beyond just strident right-wing uber-online weirdos. That is what needs replicating.

On the Need to Newspaper-ize Our Information Economy Again

In the days after the election, I sat in the sauna at the gym, enjoying a moment of quiet where I wasn’t staring anxiously at my phone. That tranquility was interrupted when three guys entered and began loudly discussing the outcome of the election. I’m glad Trump got in, the first guy said.

He proceeded to excitedly explain how Trump’s plan to replace income taxes with tariffs, unleashing American industry. Another guy piped up: I read somewhere that it’s consumers who pay those tariffs. The first man nodded, but confidently responded that everything would be offset by the disappearance of taxes. Fewer taxes and fewer imports meant higher wages and more domestic industry.

The three men nodded at each other like bobbleheads. The first guy explained he actually wasn’t a big fan of Donald Trump — but, rather, he was a huge fan of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. We’ve been letting big Pharma poison us and suppress life-saving cures for ages. RFK is going to take them on. One of the other guys piped up with an example: The FDA banned peptides! he said. Nod. Nod. Those peptides could help people recover two, three times faster. More nodding. RFK Jr is the only one talking about how chronic illnesses have been rising and how our food is killing us. Europe, they all agreed, is so much healthier: Because their food is clean, they don’t have microplastics, and because there’s no fluoride in the water. The pasta over there doesn’t even make you fat!

The unlikely audience for this confidently-incorrect conversation was myself and, believe it or not, two Ukrainian guys. We exchanged some incredulous glances but kept our mouth shut.

The biggest predictor for belief in misinformation, I always like to point out, is not a lack of education: It’s over-confidence. (Truth be told, in an era of universal untruths I’m not even sure I know what misinformation is anymore.)

There is a common belief, one I’m always bemoaning, that wrong beliefs are easily cured. Like Al Franken’s bold assertion that Air America would cleanse the airwaves of the dangerous lies of Rush Limbaugh, people seem to think that reaching the unreachable will cure them of their bad thoughts.

And yet these three guys weren’t just beholden to a bunch of bullshit, they had clearly read a bunch of information which contradicted their views. And they opted for the bullshit.

Misinformation is sticky. And it is values-driven. If you’re frustrated with high taxes, you’re willing to suspend disbelief and accept that tariffs could replace taxes and rebirth the industrial economy. I’m sure I could tie these men to a chair and make them listen to me rattle off stats — Trump’s tariff plan would raise about 8% of what income taxes currently do! The FDA banned some peptides because they’re untested and possibly dangerous! Fluoride is perfectly safe and serves a clear role! — but would they listen? And, honestly, why should they listen?

These men almost certainly got their information from a trusted source — maybe Joe Rogan, or one of his myriad copycats. We should obsess over how we can introduce trust back into the systems which tell the truth instead of simply trying to foment distrust in the systems which do not. (Dispatches #68, #102, #104)

Like I explained in the last section, that means replicating what makes Rogan work. But I also firmly believe that it means serving some desert with our vegetables.

We often imagine a time when everyone sat and read the morning paper or tuned in to the evening news out of some profound sense of citizenship. This is a myth. Yes, these were the primary sources of information for our society, and we often watched them because we had few better options. (I recall watching CNN’s Crossfire every day, thinking to myself I hate this.) But it is also true that people engaged with good journalism because it was packaged with things they actually wanted. They read a few items on the frontpage and then flipped to the classifieds. They sat through 20 minutes of international, national, and local news before the sports scores.

News was bundled with other valuable goods. Through technology and distrust, we have unbundled that product into its constituent parts — and now we’re curious and furious about why people don’t want the standalone news part anymore. We have tried covering the news in candy coating and marketing it like a new toy, but fundamentally we are running into the same problem: People don’t want to eat their vegetables. And they’re starting to get wise to us wrapping the medicine in a slice of cheese.

This isn’t a new problem. But we’re starting to see the downstream effects.

Certainly, today, if you care deeply about poverty or womens’ health, you can find lots of content on those topics. But if you remain a casual news consumer or a denizen of this ideological media ecosystem, you may only engage with those topics through headlines, screenshots, or through commentary. That is undoubtedly abstracting these real, human, issues into something fundamentally distant and unreal.

Democrats may be pulling their hair out, incredulous that women could fail to turn out in an election they tried to define as a referendum on a woman’s right to choice. But the simple fact is that regular people are far less likely to have seen a real piece of journalism chronicling the consequences of these abortion bans than they would have been, even ten years ago.

This isn’t to say that we need to go back to newspapers, the evening news, or even to our journalist god-kings again. But it is to say that we need to find a way of getting people to read news digests again: Factual briefings of major things happening across all of society, coupled with a broad array of useful, interesting, entertaining, and engaging items designed to bring new customers in. (Dispatch #83)

Maybe this will usher in a return to print, but I doubt it. Services like Apple News may replicate that snout-to-tail media again, but I remain skeptical: Analytics and algorithms, I think, have become a scourge for journalism. This is going to take some real work.

On the Need for a Plan for Victory

It is manifestly unlikely that foreign policy mattered that much in this election. Yes, some Democrats stayed home or voted for the Green Party to protest Joe Biden’s continued support for Benjamin Netanyahu’s bloody war. And some voted against the Republican Party for their platform of Russian appeasement.

One thing that clearly seemed to resonate for Trump, however, is his strong anti-war rhetoric.

That rhetoric was completely invented and contrary to his own record and policies. But as a vibe, Americans have found themselves — rightly — skeptical of war. And Trump, disingenuous as he was, succeeded in aligning his campaign with those vibes.

I won’t bother teasing out Trump’s dangerous and incoherent positions on Israel and Ukraine. But I will say: The Democrats were hurt by their own inability to chart a way out of these forever wars.

It’s tough for an administration to justify their own war, it’s even more difficult to justify someone else’s. But that’s exactly where Biden and Harris found themselves, defending Israel’s increasingly-unhinged aggression in Gaza and Lebanon, whilst simultaneously being conservative and hesitant in helping Ukraine defend itself in a war of survival against Russia.

I personally think Biden should have cut off arms sales to Israel and permitted Ukraine to conduct long-range strikes into Russia — but I think those are moral positions, not necessarily good political ones.

What is lacking in America’s position on both of those conflicts is a plan for victory.

Joe Biden never announced plans to achieve Ukrainian victory, but only to support Kyiv for “as long as it takes.” As the Ukrainians reminded me often when I was in Kyiv, there is a big difference.

In Israel, even the Israeli Defense Forces grow apoplectic about Netanyahu’s inability to articulate a “day after” — and, increasingly, it seems like he will permit some amount of annexation of Gaza. (Dispatch #101)

Voters are right to be frustrated with an administration that seems fine with continuing two atrocious wars, even as it has the power to stop both. While foreign policy realism might be wise governing ideology, it is a miserable political message.

On the Need to Stop Talking Like That

There was much discourse during the campaign about Harris’ perceived lack of policy and her reticence to sit down for long-form interviews.

Often, that criticism was rejected: The campaign has a plan! The media can’t be trusted! She does lots of interviews! She doesn’t need to do interviews! And so on.

This back-and-forth was misdirected, I think. It all assumes that the voters who opted for Trump were hanging on every detail of the campaign and just needed to see more Harris. I think that’s pretty fanciful.

But I think this idea that Harris’ campaign was thin and superficial does have some merit. In particular, it has to with how she talks.

And I should say, it’s not just her, and she is not even the worst culprit. Prime ministers Justin Trudeau and Kier Starmer, and a host of other establishment figures around the world all have this speech disease, a pathological need to talk to us like we are, and I’m going to use the technical term here, fucking idiots.

Politicians have always spoken with a particular kind of elite detachment — tightly-scripted talking points squeezed through put-on folk charm. But the increasing professionalization of the modern campaign has intensified the quest to make language vague and assuring, just as the internet has exposed both the surreal endpoint of superficiality and driven a demand for authenticity.

And then there’s Trump: A politician whose entire political identity is taking on the institutions and elites (or so he says). As political scientist Michael Alan Krasner explains:

When elites and major American political institutions enjoyed support and esteem, a candidate had to respect them, but now a candidate who was crude, aggressive, and bullying could be seen as authentic and honest.2

We’ve understood why Trump’s rhetoric works for quite some time now. But we’ve spent little time appreciating how his opponents continue being a condescending and plasticine voice for American political institutions.

This is particularly clear when you compare Pierre Poilievre, Canada’s opposition leader, and Trudeau. The former speaks bluntly, aggressively, with an air of smug bitterness. The latter has always spoken in high-minded generalities, which involves asserting intangible values so often that it borders on saccharine. (Dispatch #96)

Part of what makes modern populists so effective is their ability to make elite rhetoric absurd by contrasting it. Bernie Sanders often gets credit for his messaging and policies, but he also deserves credit for speaking to people at eye level.

Tim Walz was genuinely good at this. Watching Walz discuss agricultural prices with farmers transported you to an alternate political reality where we had never invented the campaign consultant. Walz had too little opportunity to put his skills into practise.

The few times when Harris was best on the campaign trail was when she surprised people — mentioning she was strapped, or calling her opponents weird. Those two moments broke through, and felt more like genuine thoughts than the products of focus groups. More of that, please.

Progressives should actually have a natural edge, here. Speaking the same jargon as working people isn’t just a smart political tactic, but increases the likelihood you’ll be able to engage in genuine two-way feedback. See: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez doing a one-woman campaign post-mortem with her followers on Instagram.

This is perhaps the easiest thing to fix: Stop speaking like a goddamn robot.

On the Need to Stop Being The Establishment

Once our modern liberals and leftists stop talking like the elites, they should stop acting like them.

I don’t think Kamala Harris campaigning with Liz Cheney was some extraordinary misstep, but it was certainly the culmination of a clear message being broadcast by the Democratic Party: We are your government.

People, you may have noticed, are pretty dang upset with their government these days.

Whether it’s through the media they produce, the wars they are responsible for ending, the way in which they speak, or the policies they put forward to help working people: Liberals and progressives need to stop defending and explaining why things are the way they are, and start talking forcefully, angrily, optimistically, about how things could — must — be different. (Dispatch #115)

Or else, congratulations to President Donald Trump Jr.

That’s it for this piece.

If you’re looking for even more analysis, I penned a piece for the Toronto Star about the toxic information ecosystem which propelled Trump back into the White House, and a second bit of analysis gaming out what lessons Canadian progressives could learn from Harris’ bruising defeat.

This piece is free for everyone, so please share it!

This past week, after watching Twitter descend into an even-worse cesspool, I decided to fully stop sharing links on the platform. So if you were still using Twitter to keep up with the newsletter, consider following on Notes or Bluesky instead.

Until next week!

For more radio history, listen to my podcast The Flamethrowers.

When Politicians Talk: The Cultural Dynamics of Public Speaking, edited by Ofer Feldman (2021)

Thanks for always making me think, Justin. Whenever your posts arrive, I find an excuse to pause, take a deep breath, read carefully, and reflect. And I read these more than once.

Appreciate your thoughts. I’ve been unhealthily obsessed with this election, because I believe Canada and much of the world has skin in the game. We knew the result would cause ripple effects on the future of populism, democracy, foreign interference, geopolitics, and more.

It’s going to be a while before this is all sorted out by the historians and analysts, I think. I agree with you the well-organized right-wing media did a great job of carrying a powerful and unified message. It bothers me tremendously that apparently Fox News is played without exception in all the US military hangouts. WTF?

Trumps’s quote “I love the uneducated “ captured a bunch of slaves right there. Trying to explain Project 25 to a low-information voter could backfire and seem condescending, whereas blasting “They’re eating the cats” needs no explanation and overwhelms facts.

Although the Donald and his ultra-rich CEO friends, “Muskaswamy” and the the rest of his sychophants are as “elite” as you can get, they’ve managed to fool the public that they’re just regular guys.

What a world.