There Is No Land Unhabitable, Nor Sea Innavigable

Can science and propaganda win a trade war? Lessons from the Empire Marketing Board

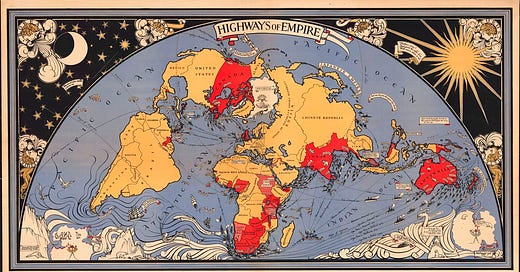

On New Year’s Day 1927, a billboard went up over Charing Cross Station in London. It was a map of the world with England dead in the middle. Spanning outwards were the roads, railways, and shipping lanes which connected London to her empire. It read:

“BUY EMPIRE GOODS FROM HOME AND OVERSEAS.”

This moment in the inter-war period was a strange one. Caught between internationalism and isolationism, the world was finally leaving the Great War behind, it had yet to plunge into the Great Depression, and a second war in Europe still felt far off.

Far from international concord, the Roaring Twenties saw a fiery trade war.

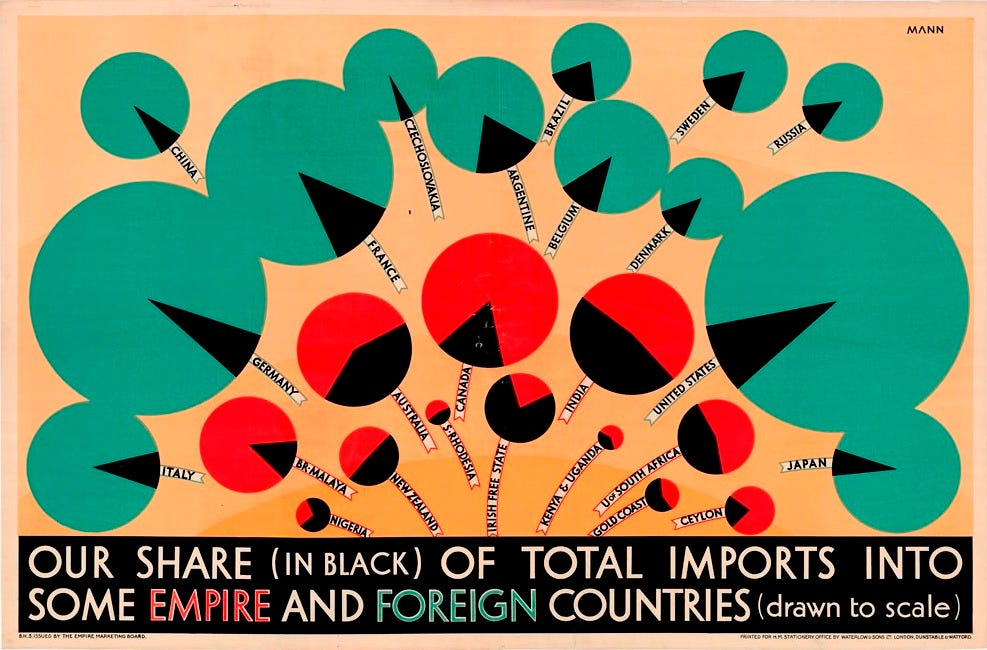

By the time the armistice was signed in 1919, the average global tariff rate amongst the world’s big economies had fallen to about 8%. That number would double in the coming years and hit nearly 25% by the early 1930s.1

One of the belligerents, then as now, was the United States. Washington’s love affair with tariffs (Dispatch #125) had ended briefly towards the end of the war, but came raging back into fashion in the early 1920s.

There was a domino effect. America’s tariffs spurred retaliatory measures from Ottawa, in particular, prompting headlines like "Two Can Play Tariff," "Canada Hits Back," "Goose and Gander Again.” Other nations joined in the fray, raising both retaliatory tariffs and protectionist measures of their own. Once Germany satisfied the terms of its surrender, it was allowed to raise tariffs again — And it did. The Nation declared that “the resentment which is felt in Canada is being shown all about the globe.”

But in the creaking and moaning structure of the British Empire, a plan to weather the economic warfare was taking shape. They called it “imperial preference” — a pledge to provide tariff-free access to each and every member of the newly-formed Commonwealth of Nations.

The other members of the Commonwealth wanted to fight this trade war with fire. But London came up with a softer idea: Propaganda. So they founded the Empire Marketing Board.

“What we wanted to sell was the idea of Empire production and purchase; of the Empire as a co-operative venture,” Colonial Secretary Leopold Amery said at the time. “Above all, as a co-operative venture between living persons interested in each other’s work and each other’s welfare.”2

This week, on a very special Bug-eyed and Shameless, I want to talk about positive propaganda, trade wars, and how the world can tackle Trump’s tariff tirade.

Before we get into this week’s dispatch, I’ve got an exciting programming note for all my Canadian and Canadian-adjacent subscribers.

Seeing as how our country is heading into a snap election with a newly-minted prime minister just as it faces one of the most disruptive trade wars in its history amid threats of annexation, I have decided to launch a stand-alone newsletter for this upcoming election.

Chaos Campaign will be a regular dispatch from the campaign trail, featuring policy briefs, interviews, post-debate analysis, live chats, and much more.

This separate newsletter will live as a new section on Bug-eyed and Shameless, but will arrive in your inboxes separately. It will be more aggressively paywalled than the normally-free main newsletter, so now is the ideal time to upgrade!

There’s a good chance you’ve already received the first dispatch yesterday evening. I had hoped to add only my Canadian subscribers to this new pop-up newsletter, but unfortunately Substack doesn’t make that possible. My back-up plan was to make the section opt-in, but Substack went and added everybody on my list instead. So to all the Brits, Europeans, Australians, Kiwis, Ukrainians, and so on — I’m sorry you will be subjected to hearing about our election. (To the Americans: I’m not sorry.)

If you received Chaos Campaign and you really don’t want to, it’s an easy fix: You can scroll down to the very end of this email and click the “unsubscribe” button — it will take you to a page that lets you opt-out of the newsletter specifically, while still subscribing to Bug-eyed and Shameless. (You can do the same on the web by clicking this link.)

If you’re confused, or you would like to receive a complimentary paid subscription, no questions asked, simply reply to this email and let me know!

Alright, back to the Empire Marketing Board.

England, arguably the world’s most successful mercantile nation, had long been the stalwart champion of free trade. But with America and Europe ratcheting up trade barriers, London found itself in a tough spot: Its exports were being hobbled by tariffs and its imports were being subsidized by its competitors, harming domestic industry.

Industrialist and Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain had long dreamed of an “alternative utopia” where Britain could be more self-sufficient, thanks to its overseas holdings. “There is no article of your food, there is no raw material of your trade, there is no necessity of your lives, no luxury of your existence which cannot be produced somewhere or other in the British Empire,” he remarked at the turn of the century, with an ominous caveat: “If the British Empire holds together.”

It was a big if. There was still top-level unity, but calls for greater autonomy couldn’t be ignored any longer. The creation of the Commonwealth of Nations in 1926 was a recognition that no one state in the Empire be subordinate to another, at least on paper. (All would still be subject to the Crown, of course.)

In this new arrangement, the overseas territories hoped to use tariffs to create a closed trading bloc for the Empire. Goods could go from Montreal to London to New Delhi and Sydney, all levy-free — but goods from New York or Berlin would face tariffs, just like the Americans and Germans did to their goods.

But London was still hesitant.

By the 1920s, trade had become mundane, at least in the United Kingdom. A child in Suffolk might sit down in the morning for a Full English and find on her plate bread made from American wheat, bacon from Denmark, tea from India, sugar from Cuba, and so on. An agricultural scientist remarked at the time that “our daily life is a trip around the world, yet the wonder of it gives not a single thrill.”

Consumers simply didn’t know or care where their food came from. But that also meant that they had come to expect this wide availability of food, at least in peacetime, and they expected prices to stay relatively stable. Scarcity and inflation would be seen as a political failure. Tariffs would cause both.

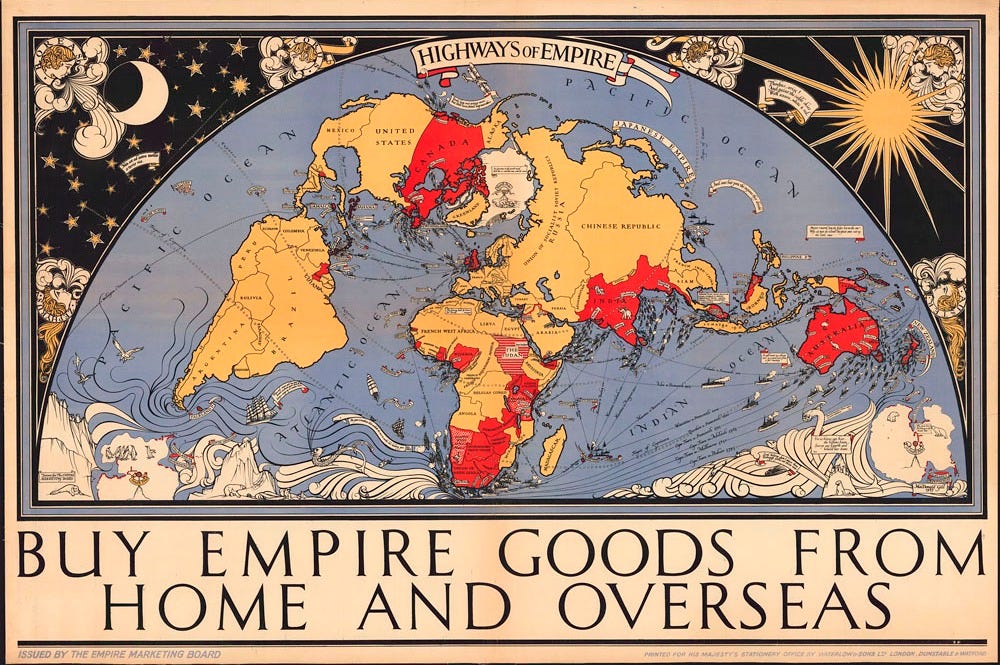

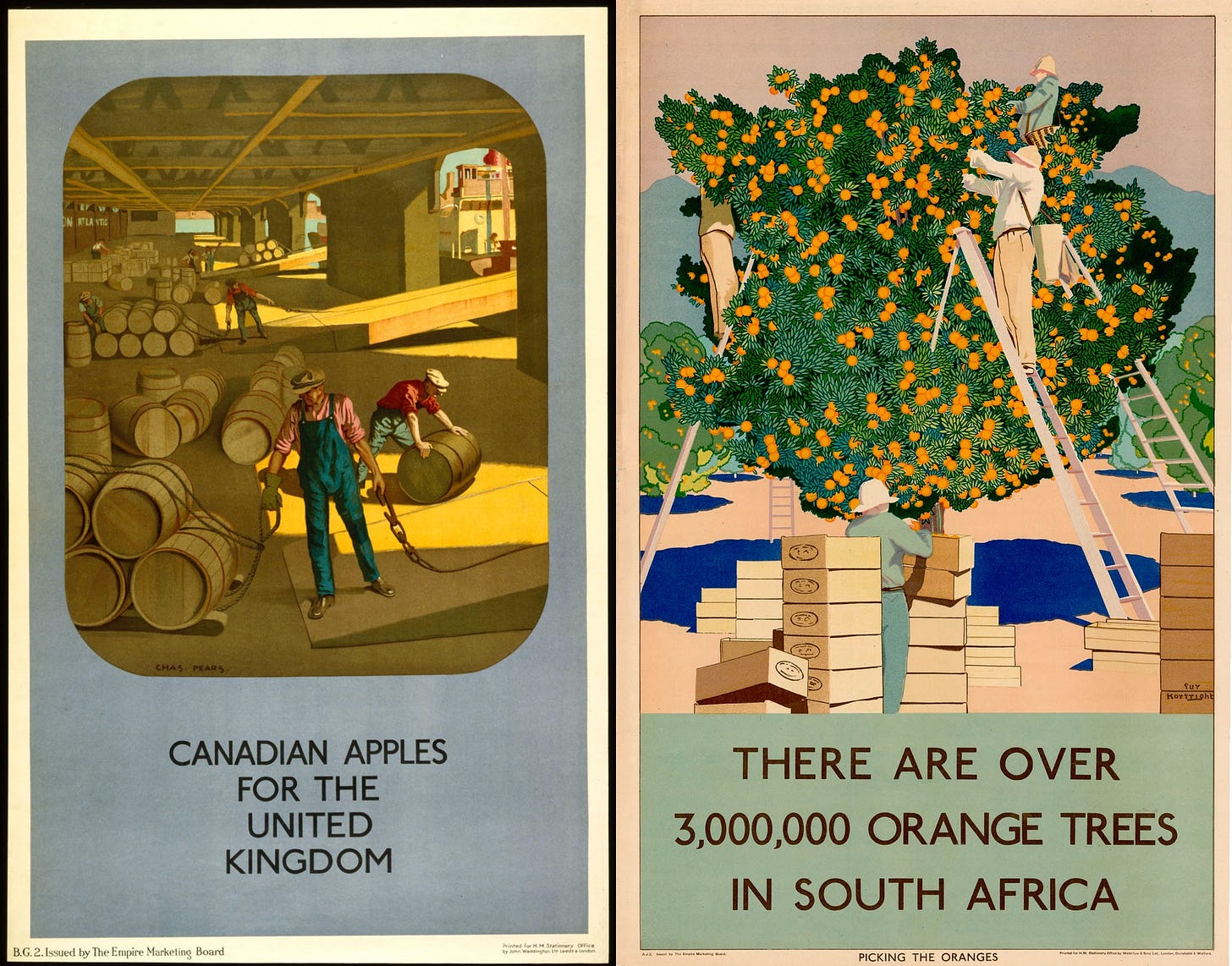

So London came up with a counter-offer for its former colonies: It would boost trade with the Commonwealth through advertising. Posters, newspaper ads, and film reels would extol the virtue of Canadian apples, South African oranges, lamb from New Zealand and tea from India. Increased trade, and thus wealth, would flow through the Empire through soft power, not trade barriers.

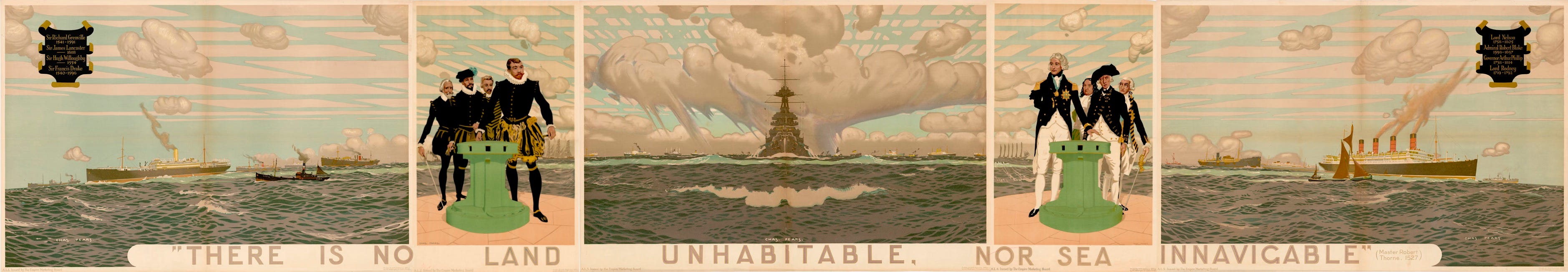

Hence the Empire Marketing Board. One of its posters proclaimed their ambitious aim, by quoting 16th century English merchant Robert Thorne:

“There is no land unhabitable, nor sea innavigable.”

It’s worth pointing out from the very outset, before anyone gets their hopes up: The Empire Marketing Board did not achieve its intended goal.

Over the seven years which it existed, the Board ran a lot of ads, but achieved relatively marginal changes in how citizens and residents of the Empire consumed goods. A 2021 assessment of inter-Empire trade over those years found no obvious shift in consumer preferences overall, and only marginal fluctuations with respect to goods specifically highlighted by the Board’s work.3

It’s for that reason that the Empire Marketing Board has been a historical footnote.

But it didn’t fail for lack of imagination and a shortage of artistic merit. The posters produced by the Board are stunning. (Many of which are available on the Library and Archives Canada website.)

In many ways, the Empire Marketing Board was mirroring the emerging propaganda coming out of the Soviet Union. It was born out of a hope that positive messaging could instil good behavior — this was before we saw the terrifying impact effective propaganda could have.

But even if it is not remembered as a success in white propaganda, the Board did stumble across some particularly useful insights — ones that we’d be smart to copy today.

At its core, the Empire Marketing Board was really asking people to do two things: To understand the provenance of their food, and to make the “ethical” choice by purchasing, tariff-free, from fellow citizens of the empire.

This effort wouldn’t stop at foodstuffs. It marketed Canadian timber and extolled the virtues of England’s advanced manufacturing. But food was a solid place to start.

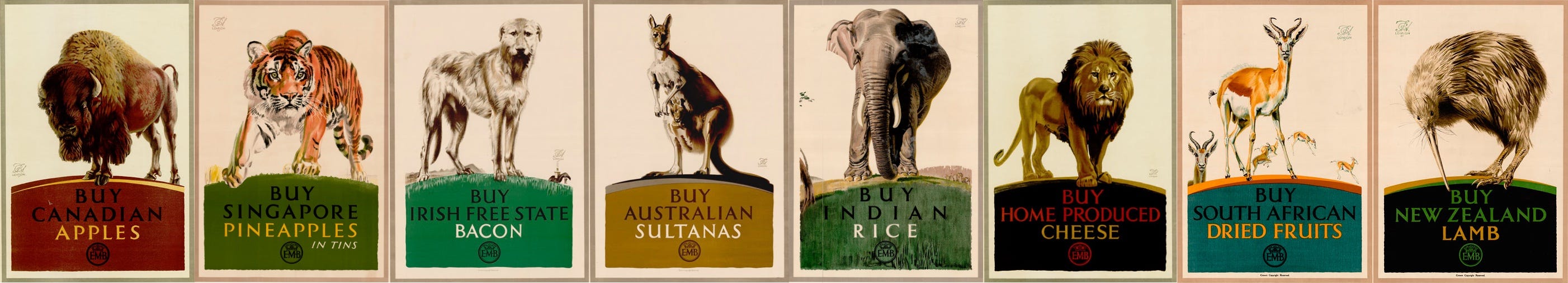

And that’s where the first real failure begins. Back then, consumers had a devil of a time actually identifying goods made in the Empire. “Exhortations to purchase ‘New Zealand’ butter, ‘Ceylon’ [Sri Lanka] tea, or ‘Australian’ beef require that these products are marked with an indication of their origin,” economists David Higgins and Brian Varian note. While consumer labelling laws were just getting going around this time, consumers generally didn’t know where their groceries came from.

To that end, they argued that the “failure of soft trade policy,” was, in part, because the Empire Marketing Board didn’t actually spend much on marketing.

On an annual budget of about £600,000, less than half went to publicity and posters. The Board hoped to ramp up that spending in time, as it figured out the sweet spot between artistic merit and propagandistic call-to-arms, but it never did.

So if the Marketing Board wasn’t spending money on marketing, where was the cash going?

They spent the majority of their budget on research. And not just on polling and focus groups, like we might expect today, but real scientific research, aimed at speeding up its ships and trains, and extending the reach of the Empire’s trade routes.

“Money devoted to research is not a luxury,” The Times wrote of the Board’s work in 1926. “It is not merely a sound investment; it is rather a condition of survival, without which the Empire cannot hope to keep abreast of its competitors in the economic field.”

This need was particularly acute because, to that point, America was spending tens of millions of dollars on scientific research to expand its exports, far more than the Commonwealth. And with a trade war in full swing, the world could hardly expect to reap the fruits of American innovation.

Shipping meat from Australia and New Zealand, for example, posed a particular challenge. The 20,000km-plus journey was made simpler by steam technology and cold storage, but it was at an inherent disadvantage — meat from Oceania had to be frozen, while meat from Europe could be shipped fresh.

So the Empire Marketing Board awarded a grant to the East Malling Research Station in Kent, asking them to come up with a scientific solution that would make New Zealand lamb competitive at the supermarket. The money funded the creation of what was then the largest cold storage facility in the world.

Something like 10% of crops were wasted due to pests, so the Board got cracking on that, too. Funds were sent to the Imperial institute of Entomology to establish a “parasite zoo” — a facility where helpful insects could be bred, studied, and then released to combat bugs that liked to feed on fruit and vegetables.

“There is no room for waste in Empire business,” the Board declared in a newspaper ad. “That is why the Empire Marketing Board has declared war on all insect pests."

Plenty, but not all, of this research was conducted in the United Kingdom. But research money also flowed to Oceania, the Caribbean, Africa, and the Americas. It was Board-funded research that toiled in researching a disease-resistant banana to replace the ailing Gros Michel variety.

This work was all painfully complex, and required good data. The Board, then, became a useful hub: A place to coordinate and collaborate with friendly governments pursuing the same mission. It, in a way, was the precursor to our modern trade pacts.

“The remaking of Empire as an interconnected, globally cooperative Commonwealth became a concept to aspire to, and it required a wide network of collaborators to achieve,” writes Ashley Bower, who wrote a lengthy thesis on the Board.

Over the Board’s seven years, it earnestly pursued the idea that trade could be both free, fair, and efficient, all without erecting trade barriers. Nations could be open to world, while referencing countries that play by the rules, while also collaborating with allies to speed up delivery, improve quality, and drive down costs.

It failed, but maybe it never really got a chance to get going.

As the 1930s dawned and the Great Depression loomed, the League of Nations held a summit to negotiate a truce in the trade war. Surprisingly, the world’s rich economies agreed. Unsurprisingly, they ignored the accord shortly after they signed it. America’s drastic Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act prompted a whole new chapter in the trade hostilities. This trade war worsened the Great Depression, causing hunger and desperation around the world.

It was here that London finally gave up on the principles of free trade. The Import Duties Act of 1932 put 10% across-the-board tariffs on all goods imported into the United Kingdom, Empire or not. The bill was introduced by Member of Parliament and future prime minister Neville Chamberlain: Son of the man who helped first build the idea of an Empire trading bloc.

The Marketing Board was shut down the following year.

At its worst, the Empire Marketing Board was little more than a rebranding effort for an imperial power in decline. Its mission, after all, was to “make the people of the United Kingdom realise the economic importance to themselves of the British Empire.”

In some cases, these slick posters were meant to paper over the monstrous atrocities committed in the name of Empire. And not all of this was history: British policies would cause the Bengal famine in 1943, and London’s indifference would kill scores.

To that end, the Marketing Board failed specifically because colonialism had failed. London’s view of this imperial trade was one where its possessions would produce raw stuff and consume finished goods. The white British were told to seek out exotic imported goods from nations that weren’t expected to research, design, manufacture, or innovate. This was, in essence, a rebranding exercise that tried to delay, or even prevent, the inevitable collapse of the British Empire.

But these inter-war years were really the last time the world had seen such an explosive and protracted trade war. This economic artillery fire made the world poorer, less safe, and more unpredictable. But it prompted creative thought and innovation, too. It was both ambition, experimentation, and liberal internationalism which kept the Commonwealth strong, and capable of fighting — and winning — the Second World War.

With tariffs back, a trade war brewing, and the world more tumultuous it’s been since then, perhaps it’s time to stop thinking in purely national terms and start figuring out how like-minded nations can make it through this crisis together.

As I write this, we still have no idea what America’s tariff rate will be tomorrow.

Donald Trump has promised, then rescinded, his tariff threats countless times over the past few weeks. Currently, America is charging a 25% surcharge on Canadian and Mexican steel and aluminium. The White House has promised to extend that tariff to include copper, though it is unclear if that is serious.

Beyond that, Trump has placed a 10% tariff on Chinese goods, and is threatening all manner of trade barrier on Europe and the rest of the world.

The free-trading world has no choice but to respond. The White House has clearly shown that it is not ready to incur the costs of a trade war, yet it continues to try and fight one.

There’s little doubt that Canada, as the first to receive this protectionist punch on the nose, is leading the way. Bourbon has been pulled off the shelves, vacations to Disney World have been cancelled, and Teslas are sitting on showroom floors. A national pride, suppressed in recent years by tough times and intense political polarization, has swung back in a massive way.

As America takes aim at her other allies — Europe, Australia, Japan — they are likely to see a similar rallying around the flag.

But this kind of defensive nationalism risks two self-defeating outcomes. The first is that we wind up in a prisoner’s dilemma: Where countries looking to lessen the impact of Trump’s tariffs will negotiate themselves out of the trade war, likely at the expense of other free-trading nations.

Canada could, for example, offer to locate more automotive manufacturing in American, breaking supply chains which run into Mexico, in order to preserve some of its own domestic manufacturing. Or Mexico could take the inverse of that deal. If both Ottawa and Mexico City make concessions, it awards Washington significantly more leverage and risks a race-to-the-bottom between two ostensible allies, with only America benefitting. If neither side caves, however, and continues to demand that the USMCA agreement be respected, they can impose political consequences on Trump in hopes that he abandons the deal, lest his party be ousted. And, perhaps more importantly, they can negotiate with each other in good faith to rewire their economies into each other’s.

There are ample fears that the United Kingdom might take Trump’s deal. London is proposing some kind of high-tech pact with Washington which, it hopes, will wriggle it out from under these tariffs. If they can get a win-win deal, good for them — but America has made very clear that it expects its allies to pick a side between America First and globalism. The order of friendly trading nations needs to make clear that you can be in the free trading bloc, or you can be outside it: You can’t be both.

If the world can steel their resolve and refuse Trump’s hard-line offers, it should resist the urge to sit around and wait until America changes its mind.

Which brings us to the second problem: Countries around the world are already descending into ‘buy local’ propaganda.

As a way to reject American goods, it’s a perfectly fine idea. But it risks self-harm.

The basic fact is that no economy can or should produce all its own goods. Canada can not build a next-generation fighter jet, France can’t grow pineapples, and Australia can’t field a decent Eurovision entry.

Instead of jingoism, the liberal order should forge something akin to the Empire Marketing Board: A global effort to prioritize economic trade with nations that respect the rules-based order, prioritize human rights, and which want to pursue economic, diplomatic, and scientific efforts to make the world a richer place.

While America’s slide into protectionism and chaos may be temporary, these tactics will also do well to counter-act the growing neo-colonialism practised by Russia, Iran, and China — the three are using debt-trap diplomacy, mercenaries, and technology-sharing as a way to expand their illiberal block and impose their own backwards ideologies on the world. A strong liberal trading bloc can and should offer the Global South a better deal.

For too long, expansive and game-changing trade deals have been just a negation of trade barriers. Instead, they should be an invitation to actually forge supply chains, trade expertise, promote good consumer behavior, and figure out the person-to-person ties that spur innovation, culture, and experimentation.

More than just a marketing effort, it should be an invitation for countries to figure out the logistics and infrastructure necessary to make this trade more practical. While we are probably all set on flash-freeze technology, we need to redouble efforts to innovate more sustainable and efficient shipping, autonomous transportation, better rail infrastructure, and (most important of all) airships.

Europe needs energy: Canada has it, but both sides seem perplexed as to how to get it from Point A to Point B. Europe needs semiconductors from South Korea, and South Korea needs Neon from Ukraine. (Dispatch #128)

In a global trade free-for-all, these efforts often ran through America. It’s clear that they can’t go that way, at least not for the near future.

How the world figures out those new trade routes is the pressing question for our current moment.

Declaring our intention, and putting up some posters, seems like a good place to start.

That’s it for this week’s dispatch!

If you haven’t read it already, check out my column in last Saturday’s Star about the work Canada needs to do to push back on a belligerent America.

Stateside, I have a deep-dive in WIRED about the cuts to the Pentagon’s threat-reduction work, which threatens how America secures loose nukes and destroys WMDs.

I was also on

this week to talk Trump’s utterly senseless trade war. It was fun!Rebranding Empire: Consumers, Commodities, and the Empire Marketing Board, 1926-1933, Ashley Kristen Bower (Portland State University, 2020)

Who Protected and Why? Tariffs the World Around 1870-1938, Christopher Blattman, Michael A Clemens, Jeffrey G. Williamson (Conference on the Political Economy of Globalization, 2002)

Britain’s Empire Marketing Board and the failure of soft trade policy, 1926–33, David M. Higgins and Brian D. Varian. (European Review of Economic History, 2021)

From anywhere, and to anywhere, except the USA, until their President respects treaties again....

Airships? Airships?!? Fuck yeah!!! Seriously though, the idea of an international rules-based and climate-aware free trade alliance is brilliant. I hope it happens. And I hope I'm alive to see the airships!