The Verdict Is In

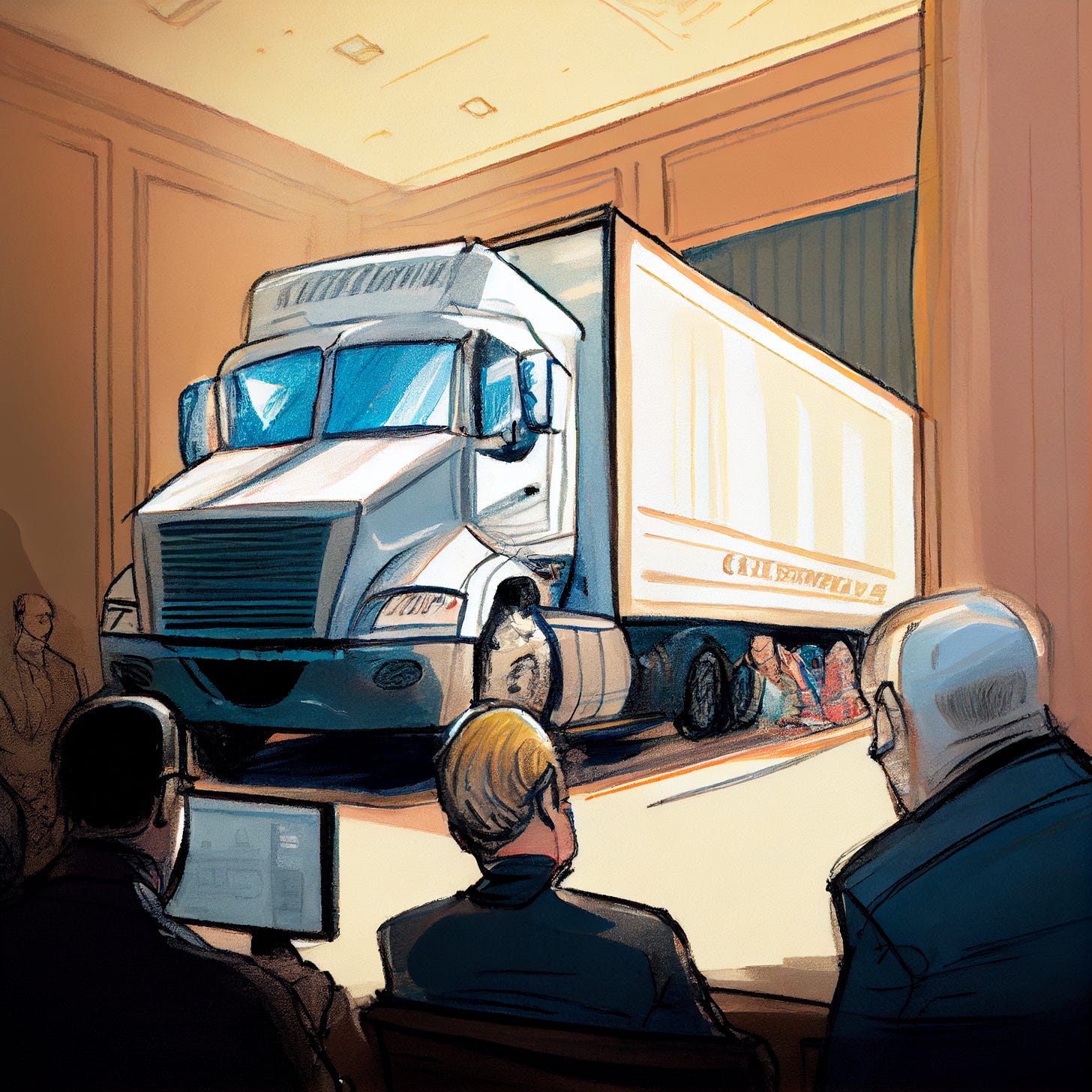

One year later, a conclusion to the Freedom Convoy. Plus: A pro-convoy documentary makes its case

“The decision to invoke the [Emergencies] Act was appropriate.”

That’s the key takeaway from the lengthy, detailed, nuanced, and dense report tabled by the Public Order Emergency Commission on Friday afternoon.

The Commission was tasked with investigating the events that paralyzed large parts of Canada last year: From the inception of a series of convoys, established to protest vaccines, vaccine mandates, and the Trudeau government; to the blockades and occupations they installed at a series of border crossings and in the capital. It was a rolling protest that spread around the world.

This week, on Bug-eyed and Shameless, I tackle some interesting beats in the Commission’s report — what it tells us about the ideology that went into the convoy, how the police responded, and how the government ultimately put an end to the occupation.

If you’re looking for some remedial reading on the Freedom Convoy, and the Public Order Emergency Commission, you can check out my past reporting for the Toronto Star, or read dispatches #12, #25, #29, or #30.

Later, a few words about The Freedom Occupation, a new documentary that puts a positive spin on the convoy. I have thoughts!

While the hearings of the Commission sometimes descended into chaos and sideshows, the mandate of the commissioner Justice Paul Rouleau was always fairly narrow. He was tasked with considering a raft of factors, including the convoy’s aims and tactics, to assess the “appropriateness and effectiveness” of how the Act was invoked and deployed.

To that end, the big takeaway is whether Ottawa acted responsibly — and, like I said, the topline answer is: ‘Yes, it did.’ But it, of course, doesn’t end there. Plenty in this report functions as a dispassionate arbiter of the whole affair. Given how differently people have interpreted the events of last January and February, that’s very helpful. But there’s plenty in here that speaks to deeper issues in our democracy: What is legitimate protest? How can we grapple with movements that have become beholden to misinformation and conspiracy theories? How do we guard against a rising domestic extremism movement? How can governments better engage with their most ardent detractors? How do we govern ourselves in a time where good faith is in short supply?

So, let’s dive in.

“There was credible and compelling evidence supporting both a subjective and objective reasonable belief in the existence of a public order emergency.”

I have been saying, since the Act was first invoked, that its application was reasonable and appropriate, and would ultimately be vindicated as such. That’s not a terribly controversial opinion: The Act is written in such a way to give the Canadian government wide latitude to decide when, and how, such an emergency should be declared.

That’s essentially what Rouleau found. Whilst supporters of the convoy insisted that there was no tangible threat to the country posed by the blockades and occupations — they tortured testimony from police officials in service of that point — Rouleau dismantles that claim with relative ease.

Rouleau points to the overwhelming evidence that right-wing extremist groups were present in the movement, to mounting calls to replace the government, to plans to hold a “Nuremberg Trials 2.0” coupled with plans to conduct “civilian arrests of those perceived to be involved with public health rules,” and to the fact that “the rhetoric of the protests also increasingly began to contemplate violence as part of a desire to achieve policy change over public health measures.” I’ll talk more about all of this in a minute.

Rouleau found that there was absolutely grounded fears that the situation “was worsening and at risk of becoming dangerous and unmanageable.” Some may reject Rouleau as a government stooge — Jordan B. Peterson is already there — but it’s hard to read his assessment and argue with the substance of it.

While we can disagree with the argument put forward by pro-convoy types, that the Act was unwarranted because the occupations were peaceful and posed no threat, it is at least a coherent position. Many, including those with the opposition Conservative Party, tried to have it both ways: Recognizing the problems posed by the occupation, but insisting that the government did not have the legal basis to intervene. That’s an intolerable position. It basically asserts that the federal government is more of an advisory body on national security and public safety, and has no authority to intervene. It’s not hard to conjure up some absurd examples showcasing just how unworkable a country we would be if that were the case.

Here’s the but. It always seemed clear to me that the orders written to put force behind the Act were far too broad. As you may recall, Ottawa not only used the Act to marshal federal resources to help clear out those occupations and blockades, and to press private tow trucks into service — it also enabled Ottawa to declare entire swaths of the country as protest-free zones, and to empower banks to freeze and seize assets without court oversight.

Speaking to reporters after releasing the report, Rouleau said that the orders written up to put the Act into force were, “for the most part,” reasonable and effective. Cabinet, he wrote, was reasonable in believing that there was a threat to national security. “There were substantial grounds for this concern.”

While I think Rouleau offers a nuanced and clear-eyed view on some of these measures, I think he tilts towards deference elsewhere. The government’s orders, for example, created wide and large exclusion zones: Geographic areas where public assembly was forbidden.

This kind of power isn’t entirely novel. Police frequently declare areas as no-go zones, normally when breaking up big public demonstrations or riots. But the orders forbade assembles anywhere that could interfere or be disruptive to vaccine clinics, any areas around Parliament, any government buildings, and a raft of other places. In effect, police could conclude that nearly anywhere in the country could be covered by this order.

Rouleau points out:

Most of the participants in the protest were engaged in the exercise of the core right protected by freedom of expression: political expression. While some protesters may have crossed the line into violence, and at times and in places, the assembly may not have been ‘peaceful,’ the fact remains that many protesters were engaged in conduct that is afforded significant protection under the Charter. For this measure to have been appropriate, it needed to be carefully tailored.

I would argue that Ottawa did not carefully tailor those measures. Someone waving a placard near a hospital — even if it had nothing to do with the convoy — could’ve been rolled up. The Emergencies Act was written to curb the excesses that were afforded by its predecessor, the War Measures Act, which allowed severe limits on protests anywhere in the country. Allowing for such a wide chill on expression strikes me as a reversion right back to that assault on civil liberties. Even if the application was, in practise, reasonable, it creates a terrible precedent for future applications of the Act.

Rouleau doesn’t agree. He found the orders to be reasonable and limited.

Where he does find the orders to be overly-broad is when it comes to asset seizures.

The convoy raised tens of millions of dollars — not just from big crowd-funders on GoFundMe and GiveSendGo, but also via other fundraising efforts, via e-transfers, and through fistfulls of cash. Once the occupation began, this money was explicitly given to finance an illegal occupation. It was clear to everyone that there had to be some limit on these ill-gotten gains.

In practise, however, those asset freezes hit individuals’ personal finances and put some organizers and participants in a position of being unable to even buy themselves lunch. Even if it was only for a short period of time, those measures sometimes continued even after the protester was back home. Rouleau found there was a “failure to provide a clear way for individuals to have their assets unfrozen once they were no longer engaged in illegal conduct.”

On the whole, however, Rouleau was satisfied that the measures were reasonable.

So, overall, Rouleau’s report is a ringing endorsement of how the Emergencies Act was invoked. Considering that this is the first time it has ever been used, and that there was simply no way to invoke it perfectly, Rouleau’s report is about as flattering to Ottawa’s decision-making process as you could imagine — it’s a higher grade than I would give them, for sure.

That said, Rouleau details some thorough recommendations on how to prepare for next time, as there will certainly be a next time. I’m not going to delve into those too deeply in this newsletter, but they absolutely need to be a priority for the country going forward. Let’s hope the various political parties put point-scoring aside and make rewriting this law to guard both our national security and civil liberties a priority.

[cue laughter]

“The response to the Freedom Convoy involved a series of policing failures. Some of the missteps may have been small, but others were significant, and taken together, they contributed to a situation that spun out of control. Lawful protest descended into lawlessness, culminating in a national emergency.”

There is no use removing responsibility from the organizers and participants in the freedom convoy. They barrelled towards Ottawa, or headed to their nearest border crossing, with the intent of causing maximum disruption until they got their way. In some cases, they wanted to remove the government or cause chaos for the sake of chaos.

There’s no real reason to think that, if Ottawa Police had successfully forbade the convoy from reaching downtown, that they would have just packed up and gone home.

But, then again, it’s hard to deny that the state’s failures emboldened this movement to step beyond legitimate protest into illegal occupation. They were essentially invited into the capital and told to have a good time. It was only after they entrenched themselves that they were told to leave. That’s a failure of the state, not the protesters.

Failing to maintain order when they did occupy downtown Ottawa continued to be a tacit thumbs-up to the occupiers’ behavior. As Rouleau writes:

I do not accept the organizers’ descriptions of the protests in Ottawa as lawful, calm, peaceful, or something resembling a celebration. That may have been true at certain times and in isolated areas. It may also be the case that things that protesters saw as celebratory, such as horn honking, drinking, and dancing in the streets, were experienced by Ottawa residents as intimidating or harassing. Either way, the bigger picture reveals that the situation in Ottawa was unsafe and chaotic.

Dancing is a valid and protected kind of expression. Dancing in the middle of a highway is not.

But if the state isn’t there to make sure one’s expression doesn’t unduly infringe on someone’s rights, particularly to personal safety, then blame isn’t just on the individual doing the Frogger tango.

“It was apparent that the police were unable to control the protest and limit unlawful conduct in the protest area,” Rouleau writes.

There will be plenty written about the policing and intelligence aspect of this. I’m going to mostly put it aside, except to say: We need to be considerably more critical about how policing of protest and public gatherings can be injurious to our democratic system. But, at the same time, failures in policing to maintain order can also be a threat to our civil liberties.

“The Government did not have a realistic prospect of productively engaging with certain protesters, like those that believed COVID-19 vaccines were part of a vast global conspiracy to depopulate the planet…I heard the suggestion that a meaningful dialogue between protesters and the Federal Government was impossible. While I do not necessarily accept that is true, I do find that the prevalence of misinformation and disinformation diminished the prospect of productive discussions.”

If you’ve been reading this newsletter for awhile, you know I’ve been struggling with the question of engagement. If we accept, as we probably should, that a core way to address the growing polarization and alienation in our society — driven by misinformation and conspiracy theories — is to have honest, frank, direct conversations with people who have lost faith in all of our institutions, then should have the government sat down with the occupiers?

Throughout the convoy and ensuing occupation, the occupiers’ narrative was that they only wanted a sit-down meeting. A face-to-face encounter with Trudeau, they said, could solve this whole problem.

That, of course, was bullshit. The assembled mass made it clear that they didn’t want a conversation, they wanted obedience. Nothing short of the Trudeau government acquiescing to their policy demands would have ben enough. Other influencers and organizers made it clear that they wouldn’t leave of their own accord until the government resigned — others went further, demanding jailtime. Individuals even called for the prime minister to be assassinated.

Rouleau makes clear that the violent rhetoric came from a minority of participants, and that the majority can’t be held accountable for the views of their neighbors in such a chaotic and decentralized event. To that end, he chided the government for making “unfair generalizations” that suggested “all protesters were extremists.” That, he said, made any kind of negotiated settlement even more unlikely.

The judge also found that the destructive and divisive nature of misinformation and disinformation that sat the heart of the convoy and occupation basically made collaboration with the federal government nearly — but not necessarily — untenable.

I think he tilts towards naive, here, but maybe that’s not a bad thing.

He also found that the convoy was “at once both the victims and perpetrators of misinformation”: A conclusion that I find both smart and incredibly frustrating.

Rouleau, like many others, doesn’t bother trying to pursue a limited definition of “misinformation.” His examples of pro-convoy misinformation include the assertion that the Commission itself was just a tool of the government, or that there was a concerted global conspiracy to commit genocide via the vaccines. When it comes to misinformation against the convoy, he points to the allegation that the convoy had a hand in committing an attempted arson in downtown Ottawa — a claim that was put forward in good faith by myself and others, with some corroborating evidence, and which was later retracted when new evidence came to light. It’s a particularly annoying accusation, because my reporting actually helped identify, or at least confirm the identity of, the individuals actually responsible. The convoy was responsible for enough bad stuff that I didn’t need to invent new misdeeds.

“Misinformation” cannot be a word to describe every error or mistake, especially not ones that are later corrected. That is a fundamental misunderstanding of what misinformation is, and why it is so corrosive. To believe in misinformation is to adopt a belief or to put something forward as fact despite the available evidence, often for ideological reasons.

That said, Rouleau is right that some coverage of the convoy was inaccurate and unfair — the failed arson is just a bad example. There have been claims that Moscow was an instrumental partner in advance the convoy’s aims, and that Russian money may have even fed the movement. Those claims have painfully little basis in reality, and have been contradicted by the vast body of available evidence. While Russian media and some pro-Russian disinformation outlets may have supported the convoy, they were marginal and insignificant, at best.

“Ideologically motivated extremists, several of whom CSIS had identified as subjects of investigation, were present at and encouraging the protests. There were numerous threats made against public officials by individuals opposed to public health measures.”

One particularly frustrating bit of gaslight that surrounds the narrative of the convoy is the idea that there were few extremists in the movement, if none at all.

Rouleau does a good job of fixing focus onto Diagolon, the loose-knit bunch of milita-wannabes who were present at the Coutts, Alberta blockade and in Ottawa.

Jeremy MacKenzie, the nominal leader of the movement, has argued that Diagolon is a vehicle for peaceful protest and that he is a “peaceful political dissident and human rights defender.”

Rouleau had none of it. “I do not accept Mr. Mackenzie’s evidence in that regard,” he writes. “I am satisfied that law enforcement’s concern about Diagolon is genuine and well founded.” He points to Diagolon symbols being sewn onto bodyarmor seized in Coutts, and MacKenzie’s ties between heavily-armed men who are accused of plotting to murder police officers.

Although he did not travel to Coutts, Chris Lysak, a Diagolon community member with whom Mr. Mackenzie had met previously at a Diagolon event, was in Coutts and was arrested as part of the police investigation into the presence of weapons. The RCMP believes that the ballistic vest displaying the Diagolon logo was Mr. Lysak’s vest. In addition to Mr. Mackenzie’s connections to Mr. Lysak, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) reported that Alex Vriend, a friend of Mr. Mackenzie’s and a Diagolon supporter, collected donations to pay transportation costs for protesters to both Coutts and Ottawa.

This is all a useful reminder that anyone who suggests that extremists were nowhere to be found during this movement is being willfully obtuse. Both MacKenzie and Vriend were in Ottawa, they have both made repeated calls to hang or murder the prime minister, and they have both lied about their ties to the crew arrested in Coutts. They are domestic extremists, and anyone carrying water for them should give their head a shake.

“The Freedom Convoy garnered support from many frustrated Canadians who simply wished to protest what they perceived as government overreach. Messaging by politicians, public officials and, to some extent, the media should have been more balanced, and drawn a clearer distinction between those who were protesting peacefully and those who were not.”

As I’m going to talk about further down in this newsletter, we’re going to need to figure out what dialog looks like. That cannot mean compromise on matters of fact and reality — we can’t split the difference and say the vaccines have only killed tens of thousands, not millions; or that Klaus Scwab only secretly controls world leaders on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday.

But it does mean having a bit of grace. We will need to have a real conversation about how public health measures designed to combat COVID-19 were, at times, not based in science — sometimes using civil liberties-infringing measures that clearly had no benefit, and at other times doing too little to prevent transmission of the virus.

Rouleau summarizes the problems well:

First, whatever their merit, these public health measures imposed genuine hardship on Canadians. Second, some of the rules implemented by governments caused understandable confusion and even anger among the public. This is not to say that the rules themselves represented bad policy, only that some measure of negative public reaction was understandable. Third, at a time when the pandemic forced many people to live their lives online, it is not surprising that social media was actively used as a means for individuals to express their displeasure with government actions.

There remains a real unwillingness to echo those points. Doing so now will not take the air out of the continuing anti-vaccine movement, but it couldn’t hurt. It would be a significant mistake to wield Rouleau’s report as vindication without reckoning with his diagnosis for how and why people decided to drive to Ottawa.

We also can’t put aside that, while the organizers tended to be advancing long-held grievances against the government, many participants joined because they felt that they had no other effective way of making their voice heard. That’s an interesting problem with no obvious solution. It seems obvious, I think, to many people that rebuilding faith in our institutions is a must — but it’s less obvious that we need to admit that our institutions are, if not broken, at least working less well than they used to. Admitting those weaknesses and working to fix them may be a good way of generating goodwill on both sides.

Last year, I received a request from Rachel Emmanuel: Would I consider sitting down for an interview for her upcoming documentary on the freedom convoy?

Emmanuel was fairly upfront, that the documentary would take a pretty flattering look at the convoy and ensuing occupation. But, Emmanuel promised, she was keen to hear from critics and skeptics as well, and that the documentary would take a balanced look at the whole affair.

I like to think I’m fairly good at sussing out earnest requests from traps — there are absolutely media outlets out there who would love to get a lamestream journalist in an interview, just to pepper them with deranged and delusional questions, for the spectacle. Nevertheless, my malicious intent radar is not infallible.

But that radar didn’t ping, so I agreed to sit down with Emmanuel for an hour this fall. Midway through the conversation, I started getting the feeling that she was going too soft on me, not too hard. A new anxiety arose: Was I being given the villain edit? The rube journalist who still believed in vaccines, in spite of the devastation they caused.

There wasn’t much to do about it, then, so I wrapped the interview, shook Rachel and her co-producer/brother’s hand, and wished them good luck.

The documentary dropped last night, released via right-wing independent media outlet True North. And, honestly, I was pleasantly surprised.

The documentary is perhaps one of the easiest formats to peddle propaganda and misinformation. Done right, of course, the documentary can be an unflinching investigation into a single topic that carries emotional resonance just not available in other formats. In the wrong hands, a documentary can manipulate our emotions and overcome our innate skepticism to lead us into fantasyland — that’s true of everything from Loose Change, which helped popularize the 9/11 inside job theory to Kony 2012.

But The Freedom Occupation, at least generally, doesn’t play that game. It ping-pongs between supporters of the convoy and skeptics. While I definitely don’t agree with some of the assertions of the piece — there is genuinely no evidence, for example, that police successfully launched tear gas against the occupiers — it nevertheless offers good nuance and balance, no matter your views on the convoy and ensuing occupation.

You only have to look at the comments to appreciate that not everyone was keen to hear views that challenged their own — that includes Rupa Subramanya, a National Post columnist and unwavering supporter of the convoy.

But I think Emmanuel makes a very cogent point about how projects like this can get some disparate views in the same room. Here’s her talking with friend of the newsletter Andrew Lawton about that phenomenon:

Andrew Lawton: I do think that's been one of the problems with the Convoy: It’s that there have been a lot of people that have their baked-in perspective, they refuse to — not even just agree with the other side — but just respect that there is another side. And I get from what you've said, Rachel, that you're not trying to force people to believe a certain thing, but do you want people to, at least, say: ‘I understand the other perspective a bit more, I understand where they're coming from a bit more’?

Rachel Emmanuel: Yeah, absolutely. And, as we spoke about earlier, there’s just that need to still be willing to have dialogues with people that you don't agree with. […] We don't want to lose that ability to have dialogue with one another. I don't think we're going to see the progress in our country that we want to see, if that's the attitude that we have.

It should be an uncontroversial point. But it’s one that I think we need to keep in our heads a little more often, these days, because crosscutting dialog is becoming a rarer and rarer thing.

So give The Freedom Occupation a watch — even if you viscerally disagree with the editorial point. Leave your thoughts in the comments below: I’m curious to hear them.

That’s it for this week. I was all set to finish tapping out a very different newsletter this week, when word came that the report was set to be released Friday. So paying subscribers will likely get some extra Bug-eyed and Shameless next week.

Good synopsis Justin. The dialogue issue has me torn. I've failed locally to move the needle with the hard core group. However what has started to happen is that many in the quiet minority have come to me privately to get my take on things. They figure I would "know what the facts are". Most recently it's been the 15 minute cities issue which is so conspiracy laden in my neck of the woods it almost defies belief. So while these people won't be standing up and giving speeches they will be engaging in conversation around the dinner table and in their social circles. What we are doing then is removing the opportunity for growth where we don't want growth. I look at it like management of a feral cat colony. Spay/neuter prevents growth and over time the colony size shrinks and eventually just disappears because most feral colonies don't to take non members kindly.

Feral cats? Great analogy!