Take the Skinheads Bowling

The online far-right is living in a fantasy world. What if we visited them?

“Instead of destroying Jordan Peterson with facts and logic, I’m seducing Jordan Peterson with facts and logic.”

It’s a line that, a year after it was first uttered to me, mid-giggle, continues to bounce around in my head. Partly, sure, because it’s an interesting concept — and partly because it invokes a hellish tableau of someone trying to entice Professor Meat Sweats home from the bar.

The line may be a tad egotistical from anyone other than Natalie Wynn. But from her, it’s just a statement of facts.

You may know her better as ContraPoints.

For nearly 15 years, Wynn has been uploading videos to Youtube: Tackling politics, religion, gender, philosophy, and everything in between. Since 2016, after “it’s about ethics in video game journalism” became the rallying cry for an online anti-feminist backlash, she booted up the ContraPoints channel.

In terms of production quality, cleverness, research, and theatrics — you can’t beat ContraPoints.

Over the past few years, there’s one question I’ve been asked with some regularity: What do we do about this?

This being the rise in conspiracy theories, a surge in paranoid populism, a mounting domestic extremist movement, even a concerted effort to overturn democracy in the crucible of Western liberalism.

I, of course, can’t answer that question properly. If I could, I’d probably be out there waving my magic deradicalization wand.

But more and more, I think the answer is one that we — I include myself in this — originally discounted as counter-productive.

We, and I don’t say this lightly, need to take the skinheads bowling.

I interviewed Wynn last year for a piece in Foreign Policy, where I asked the question: Can online radicalization be prevented by old-fashioned political debate? At the time, I admittedly wasn’t sure if the answer was “yes,” “no,” or somewhere in-between.

I had embarked on the story after hearing from a moderator on Bunkerchan — what was, at one time, /leftypol/, a board on the notoriously grotesque imageboard 8chan. They had since decamped to their own website and, clearly, wanted a bit of positive press.

But Bunkerchan, named in honor of Albanian Communist leader Enver Hoxha and his tens of thousands of bunkers, was intriguing to me. Whilst the rest of us on the surface were hectoring everyone who shared misinformation with our indeterminable fact checks, bemoaning the attacks on our precious institutions, and hoping that the much-vaunted “adults in the room” would temper the base instincts of Donald Trump and his compatriots — the very-online users of Bunkerchan were deep underground, trying something crazy:

Arguing with the radicals.

The idea of ‘raids’ has always been popular amongst the chan crowd, probably owing to a childhood of playing World of Warcraft. For years, 4chan made a point of going, en masse and at the same time, to another corner of the internet and wreaking havoc.

4chan, 8chan, KiwiFarms: All peddle in the idea that they are a digital biker gang, driving around and hassling anyone who looks at them funny. The idea is not to convince anyone of anything, but just to look tough and edgy.

So Bunkerchan flipped that idea on its head: Let’s show up and actually talk to them.

Bunkerchan is basically a carbon copy of 4chan: There’s the same edgelord humor, the same dumb memes, the same blanket anonymity. It’s just that, instead of 4chan’s notoriously alt-right political philosophy, Bunkerchan is full of downright Communists — in every shade and flavor you can imagine.

For those who have steeped themselves deep into the chaotic counter-culture of 4chan, who can’t imagine an online identity where Pepe isn’t ubiquitous, Bunkerchan is the next closest thing. Those leftists’ reactionary, anti-identity politics, grudge-riddled ideology matches up pretty well with the alt-rights reactionary, anti-identity politics, grudge-riddled ideology. And Bunkerchan certainly claimed to be a refuge for many ex-4chaners.

Now, I don’t want to hold Bunkerchan up as some perfect model to emulate. The chan doesn’t, technically, exist anymore: A series of internal schisms (which I, apparently, played a role in) led to its shuttering in favor of the now-dominant /leftypol/ chan. And actually reading their boards is an exercise in arcane Soviet revisionism, pro-Russian tankie-ism, and general trolling. Which is fine, I guess, if that’s your bag.

But Bunkerchan had just gotten me thinking: Do we, in our attempt to prevent online radicalization, need to start looking at digital space in more physical terms? That is: Are these problematic communities, that serve as a sort of primordial soup for online extremism, places where we can actually go, and try to change?

Let’s go back to Wynn: When she first emerged on the Youtube scene, its politics was dominated by a fairly uniform bunch of vaguely progressive atheists and philosophers. Don’t ask me why, it just was. (As a one-time semi-religious reader of Pharyngula and watcher of QualiaSoup, I confess I counted myself amongst them.) That suited her fine.

But amidst that ideological shift, starting around 2014, the internet decamped in a rather interesting way. Many spaces that had been notionally progressive — or, at least, politically agnostic — had suddenly identified with a new, uber-online, brand of reactionary anti-feminism. While too much has probably been made of Gamergate’s role in shaping politics writ large, it was clearly a shifting point for many online spaces: It was the point at which 4chan became consumed by this far-right ideology, when Youtube began to host various chauvinistic dickheads, and where new networks of like-minded men began to situate themselves.

To imagine this, it helps to dispense with our accepted view of the internet as sort of a limitless plane — where everything is simultaneously infinite, but bundled together. Sometimes, I hear people refer to the internet, as in the place they know and are familiar with; and the deep web, the areas they’re not. Imagine someone referring to Times Square as New York City, but carving out a grubby dive bar on W 44th street as Dark New York.

There’s a 2012 paper, in the Journal of Science in Society, that tries to grapple with this. The internet isn’t space, they say, but it’s not some ethereal gas, either.

Rather than being undifferentiated and boundless, cyberspace is distinct and bounded. It is not simply a random and unconstrained collection of possibilities but is imbued with recognizable opportunities and supported by behavioral guidelines. Rather than an empty void or unfamiliar extension, cyberspace is at once inhabited and inhabitable, supporting many of the everyday activities of human experience. Thus, we reject the contention that cyberspace is simply a “space” and conclude that cyberspace is simply a spatial metaphor for the familiar places of the digital environment that have become, for many, such an essential part of everyday life.

Let’s put that in real people terms: When you log on to 4chan every day, you walk into a familiar room. You know where the light switches are, you know where the door is. You might not know everybody by name, but you know you all speak the same language. You can pick up on a conversation that began yesterday, or make a reference you know everyone will get. It’s not just one pub with all your friends, it’s a sprawling metropolis, and you just happen to know all the spots you like — where you might walk straight past Times Square and head to Jimmy’s Bar.

To keep torturing this metaphor, which is what we must do when we visualize the internet, if someone of an exact opposite ideological persuasion walks into Jimmy’s and pull up a bar stool: That has an immediate disrupting effect.

And that’s exactly what Wynn did. As Youtube turned alt-right around her — and as many other progressives fled — she fought back. She pulled up a stool.

Youtube’s algorithm, particularly at that point, privileged engagement above all else. The longer you watched, the more videos you binged, the more you commented — the more it would feed you what you wanted.

But Wynn had found a way to wedge herself into that space. She gamed this positive feedback loop so that when a Peterson fan was deep into a 23-video binge, served up by Youtube, her video might be 24th.

Wynn provided people with humor they got, in a format they liked, in a way that spoke to them as thoughtful people, that attacked the worldview sold to them by the overwhelming majority of their media diet. And it worked. People liked it.

One thing that has always bothered me about the way in which we discuss far-right radicalization — as opposed to, say, how we discuss religious radicalization — is that we seem to concede the information war before it’s even begun. We talk more about banning content, or fixing algorithms, or force-feeding users holier-than-thou fact checks than we do about providing them content they actually want that challenges their crystalizing worldview.

This sort of disruption was basically impossible, or unwanted, on traditional media platforms. Right-wing radio stations didn’t want to spoil a good thing by stuffing anything more than a token lefty on the dial (liberal punching bag Alan Combs being a prime example.) TV perfected the theatrics of the right-vs-left debate format, a la Crossfire (liberal punching bag Alan Combs being a prime example.) And even then, right-wing stations like Fox News offered ideology homodoxy for the masses.

With the internet, the barriers to entry have been torn down. Perhaps the average person can’t burst onto an episode of The Joe Rogan Experience, but they can sure log onto the message boards that Joe Rogan fans frequent, or set up their own karaoke version of his show without suffering from Rogan’s patented brand of slack-jawed gullibility.

It is foolish to look at individual influencers — Rogan, Peterson, or as one media outlet recently pointed to, Ben Shapiro. Sit and actually listen to these guys, and you’d be hard pressed to identify anything truly radical. Idiotic, transphobic, didactic, disingenuous: The so-called Ideological Dark Web is certainly not a positive influence on society today, but they’re hardly encouraging domestic terrorism or a total decoupling from reality. Nor are they even, necessarily, a gateway drug, and we need to stop talking about them as such.

Indeed, you could listen to Shapiro’s show daily and balance it out with, say, Wynn or the incessant hectoring of the progressive Young Turks crowd. Many do exactly that.

Thinking, again, of the internet as an actual physical space: Where we need to be worried is when people give themselves a daily routine that entrenches them into a particular set of grievances, and encourages them to retreat further from the general conversation into particularly angry fringes of it. Visiting Shapiro’s pop-up shop isn’t bad, in and of itself, but if he is just one stop of many, each more illiberal and furious than the last, then it’s something that should worry the rest of us.

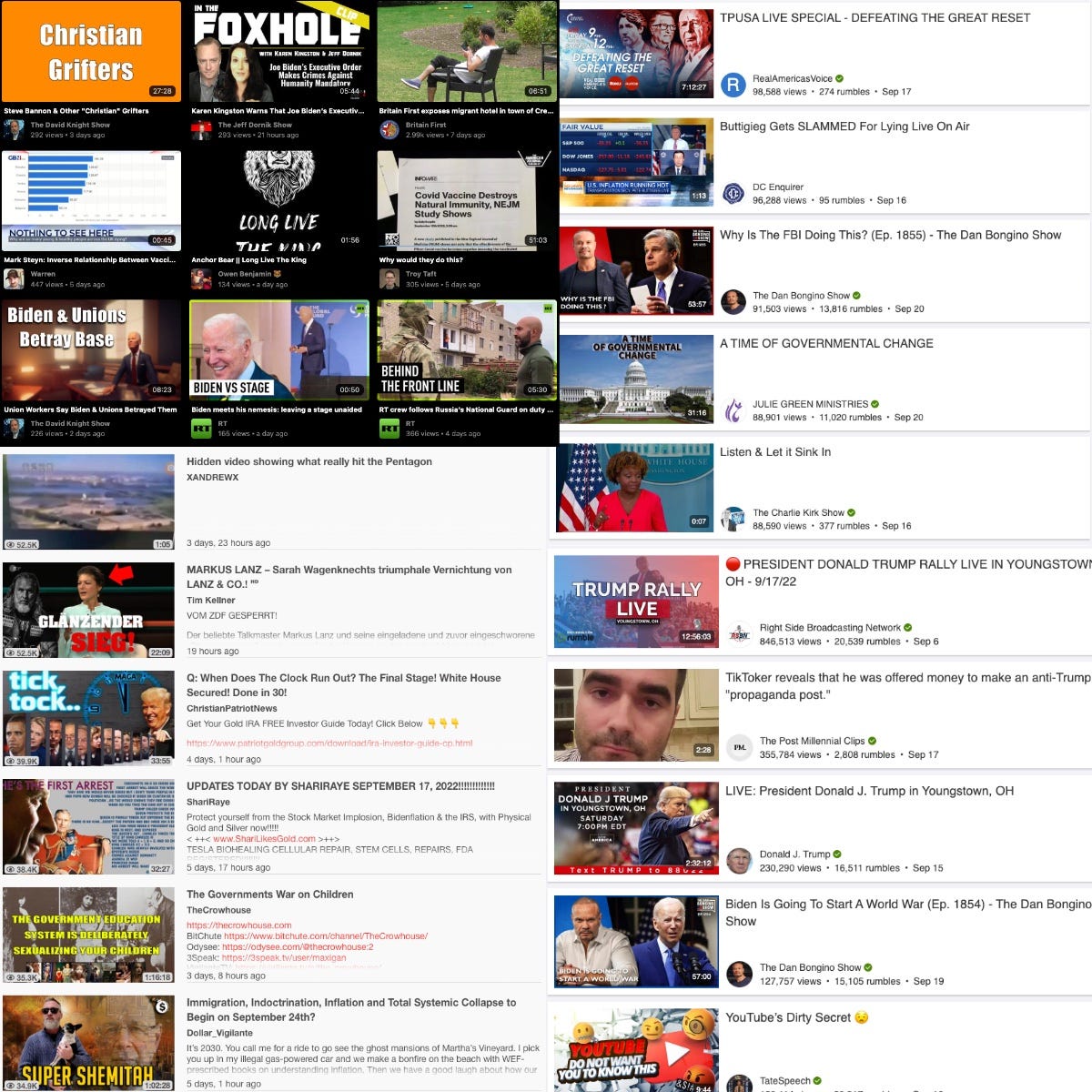

That is, someone who logs on to the internet to watch Peterson’s new daily screed, then hops onto a private Discord to rage with like-minded fanboys, where someone may share the newest explosive allegations from the Pfizer Papers, so they turn to their favorite Telegram channel to get the full scoop, then follow the thread to a 40-minute Rumble video about the safety risks of the vaccines. At the end of their day of research, they could be listening about the coming civil war certain to destroy society, and shopping for water filtration systems.

There are people in these spaces who are, and who have long been, radicals, racists, extremists, and wannabe domestic terrorists. Much in the same way there are angry, bitter young men who have sought out neo-Nazi clubhouses in the real world, there are people who log on with the express purpose of situating themselves amongst other miserable sods who blame women, queer people, Black folks, and immigrants for all their woes. That problem has remained more-or-less constant for decades.

What is novel and needs solving for are the people who slowly, inch by inch, submerge themselves into this world. Some do it deliberately, some do it thanks to the algorithm, some consider it edgy, some are just bored. Many of these people are quite smart. They may hold plenty of liberal, or even progressive, views. They may see no conflict between, say, their total acceptance of gay people and their belief that the Democratic deep state is using gender theory to destroy men.

Not all of these users even fit our traditional definitions of radicalization. Only a tiny fraction of the very-online alt-right, QAnon, anti-vaccine crowd are likely to commit a mass shooting, or to detonate a suicide vest. The number is not zero, but it’s comparatively small. More worrying — as January 6 showcased all too well — are people who have adopted such a deranged worldview that violence isn’t the means or the ends, per se, but an acceptable reaction. But even they may be a minority. The bigger proportion are people who are launching an information war: Against the news media, against vaccines, against government institutions, against a pluralistic society.

We should probably abandon the idea that we can really prevent wrongthink. The goal can’t be to convince followers of QAnon to go join the Democratic Socialists of America, to convert the driver of a truck covered in STOP THE STEAL stickers to volunteer to be an independent election monitor, or to cajole a Moderna-microchips-the-masses influencer into getting the COVID-19 vaccine. People are allowed to be wrong. They shouldn’t be unchallenged, though.

Disrupting these insular spaces could be a matter of putting some water in the wine — pushing users to realize that they are not exclusively amongst like-minded individuals. Making these spaces less uniform could also encourage more diverse content: Making their social media and video feeds less unanimously apocalyptic. Give them something else to think about — take the skinheads bowling, in effect.

Amarnath Amarasingam, an expert on extremism, tells the story of Arno Michaelis, a former white supremacist who successfully deradicalized and now helps others do the same: “He used to have Seinfeld videos marked with his niece’s birthday marked on the cassette, because he knew if any of his friends came over, he wasn’t allowed to watch a Jewish comedy.” It’s probably a stretch to say Jerry and the gang directly deradicalized Michaelis, but they sure didn’t hurt.

Wynn put this quite well. Even having a single, effective, counter-weight to this hard-right worldview: “It’s a check on letting an ideology grow into a mutant.”

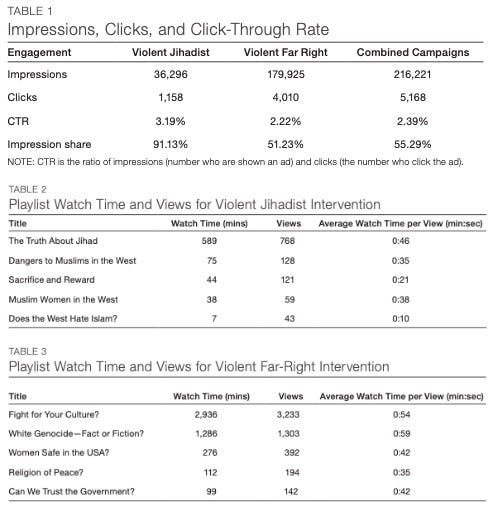

We have experimented with this a little bit. Moonshot, a counter-radicalization group, took the interesting approach of using Google AdWords to target both those engaging in Islamic extremism and right-wing extremism. The idea was, in their words, to “prevent unobstructed access to extremist content.” Did it work? Kind of.

Those looking for extremist content on Google were, perhaps to a surprising amount, willing to click on ads served by Moonshot — leading them to counter-radicalization videos that they, at least briefly, watched. Figuring out its impact beyond that, as one Rand report found, is notoriously difficult.

There are some obvious problems with this plan. For one, relying on Google advertising is a painful mistake. What’s more, out-of-the-box counter-radicalization videos are just fact checks by another name — they are not compelling to the always-online cynics.

Disruption needs to be a mix of arguing, debunking, humor, and off-topic jibberjabber, perhaps about bowling.

How this looks in practise will be more difficult to define. Bunkerchan and Wynn offer particular examples, but they are perhaps not eminently repeatable. Not everyone wants to log on to 4chan, nor should they. Youtube, meanwhile, is no longer suffering from the same algorithmically-driven groupthink it once was and probably doesn’t need saving.

In fact, the major social media platforms are no longer really the problem. Maybe kicking QAnon off Facebook, and shutting down Twitter accounts that harass queer people was the right approach for all of our collective sanity. But it’s worsened the radicalization problem. To rectify it, we need to meet these people where they’re at and do it intelligently. Conspiracy theorists and extremists who still use these platforms do so for limited reasons — perhaps to flood the comments or replies in an attempt to red pill the masses by disrupting our tidy liberal world with their reactionary flamethrowing. Or, perhaps, they want to follow the latest chess drama.

Where this alternate reality thrives is on the counter-programming channels of Rumble, Odysee, Bitchute, Gab, Parler, Truth Social, Telegram, and so on. They provide the illusion of intellectual diversity while, in fact, dragging their users deeper into the mud. Figuring out what disruption looks like on those channels is tricky, but very important. What is absolutely certain is that governments cannot be leading the way on this. This is a problem for the rest of us.

This whole appeal: It’s not an invitation to debate neo-Nazis on whether or not the Holocaust happened. It is not an appeal to argue whether trans people exist or not. Platforming debates in mainstream spaces, on extremists’ terms, isn’t disrupting their world, its disrupting our’s.

So does this mean pivoting to Telegram, broadcasting to Rumble, truthing on Truth Social? I don’t think it will be that easy, but we’re going to need to start thinking in those terms. We’re going to need to start recruiting more ContraPoints.

The habitants of these little hobbit-holes won’t like it, of course. As Wynn points out in one of her videos: “[Fascists] do not care about ‘diversity of opinions’—in fact, they actively oppose it.”

In the coming weeks, I’ll be doing some subscriber only open threads, to open up the conversation a bit. And you can expect a few subscriber-exclusive newsletters in the near future, as well.

Until next week.