So You've Become a Russian Asset

I testify on the nature of Kremlin info-ops. Things get weird.

Winston Burdett, a theatre critic for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, joined the Communist Party USA in 1937.

It wasn’t terribly shocking that a union newspaper man would become a card-carrying member of the Reds. When Burdett’s paper went on strike, protesting for more pay, he led the picket line. When merchants and subscribers needed to be encouraged to cancel the Eagle during the strike, Burdett joined the posse of irate newsmen to do some door-knocking. But his ambitions went further than Brooklyn: When war broke out in Europe, Burdett packed up and jetted off to Finland, then Norway. A freelance reporter at first, he was soon picked up by CBS radio.1

The journalist joined the unbelievably brave corps of reporters who risked life and limb to cover the European theatre — losing colleagues and his fiancé along the way. After the war, Burdett became a protégé of storied anchor Edward R. Murrow and would go on to cover a season of revolution in the Arab world before covering the Vatican from Rome.

But Burdett’s past party membership almost derailed his career. As anti-Communist mania swept America at the dawn of the Cold War, CBS sent a loyalty questionnaire to its employees. On it, Burdett confessed his party affiliation, which he said had long since lapsed: Still, the executives panicked and rushed him back stateside.

CBS let Burdett keep his job, so long as he submitted to questioning from the Commie-catchers at the FBI. He dutifully marched in to be interviewed by the G-men, where he proved his allegiance by naming names of Communists at the Eagle. But he, Burdett insisted, was no Red.

It took a month for Burdett to crack. He rung the FBI back up: Not only had he lied about quitting the Party, it was the Communist Party USA who had financed his move to Scandinavia in the first place. He had liaised with a Soviet handler in Stockholm, where he was tasked with probing Finnish morale during the Winter War. He was assigned to clandestine work across Eastern Europe and Turkey.

But Burdett was also a crap spy. When he was sent to Romania to make contact with the Russian embassy, he didn’t receive a reply — so he left. In Yugoslavia, a cable told him to meet a man wearing one glove at a Belgrade tram stop, who in turn gave Burdett the coordinates for his next meeting. Burdett bungled the address, gave up, and left his contact waiting.2

Burdett had, genuinely, quit spying and the Communist Party in the early 1940s. During his short and unimpressive career in the clandestine arts, he had not betrayed his country nor, at least in his telling, did he give the Russians anything that wasn’t already published in the newspaper.

Still, Burdett became the focal point of a Senate investigation into Communist infiltration of America. He named names and began warning about the threat of malign Soviet influence. He even accused the Russians of killing his lover, an Italian anti-fascist who, Burdett said, was killed by the Soviets for his betrayal.

While Burdett became an early piece of evidence for the Soviet’s much-feared and far-reaching network of assets, I look back at Burdett’s inept experience at intelligence work slightly differently. For just a few thousand bucks, the Soviets had essentially commissioned a few articles from a freelance journalist and caused themselves more headaches than they likely wanted.

This week, on a very special Bug-eyed and Shameless, I want to talk about the people who find themselves doing the bidding of the Kremlin: From the useful idiots who (allegedly) took rubles to sing Putin’s praises; to the Canadian journalist (allegedly) recruited as a KGB asset; to Elon Musk’s (confirmed) secret bromance with Vladimir Putin.

On Thursday, I testified before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security, on the threat of Russian meddling.

I’m not huge on the idea of journalists testifying before Parliament/Congress, because of the risk that such testimony will conscript us into partisan squabbling or otherwise compromise the independence of our work. But, in the context — where this ought to be a perfectly non-partisan issue, and where my work on the matter has been on the public record for years — I thought it pretty safe.

You can watch the whole committee hearing below. I won’t bother recapping much of my testimony, only because longtime Bug-eyed and Shameless readers will recognize a lot of it. (Dispatch #45)

Instead, I want to talk about the rather shocking testimony from my co-panelist, Chris Alexander, a former Canadian diplomat who served in Moscow and Kabul before becoming Canada’s immigration minister. Off the top of the committee hearing, Alexander handed over seven documents which, he said, tell an eye-popping tale of Russian skullduggery in Ottawa.

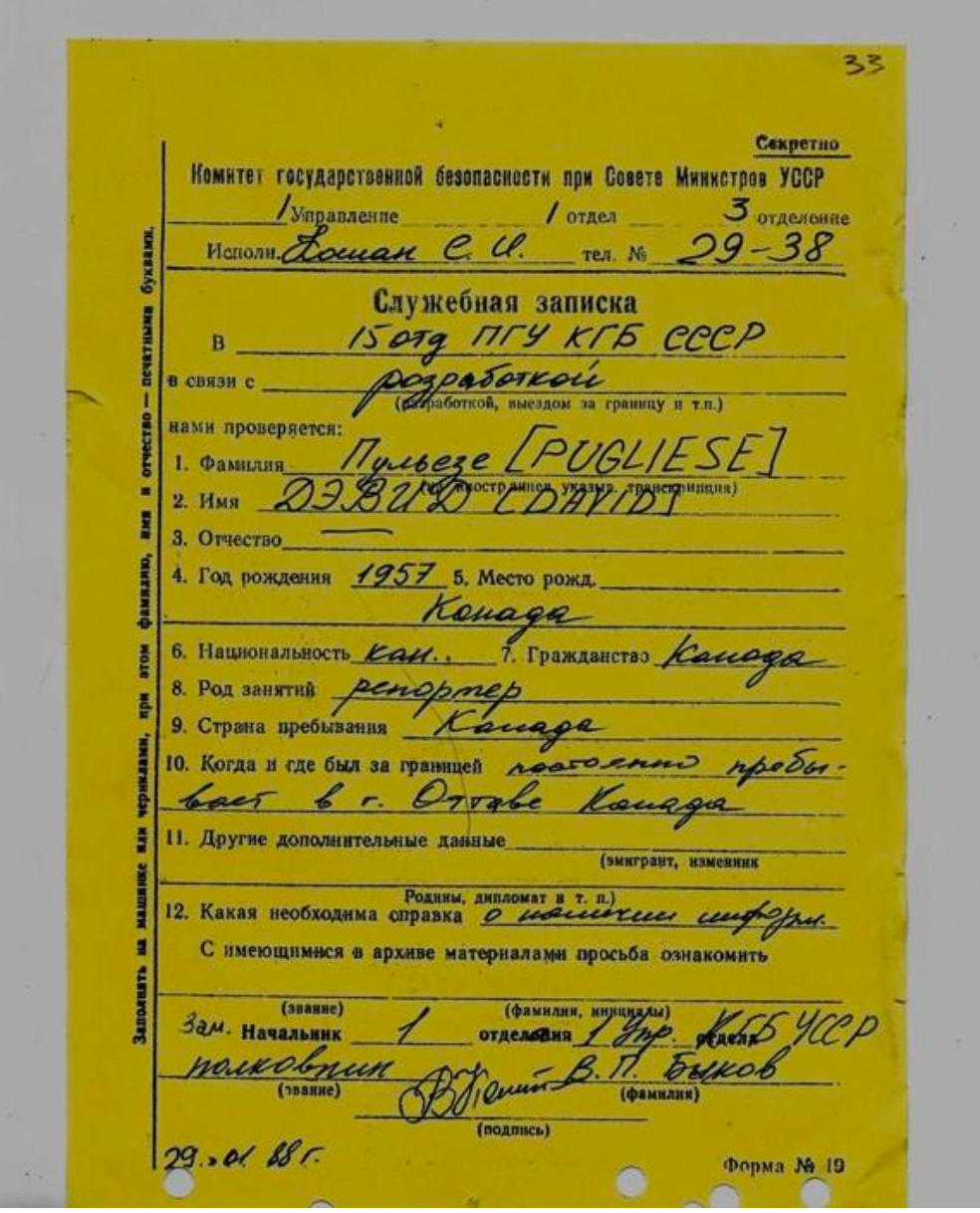

Chris Alexander: In a nutshell, these records document a KGB operation to talent spot, recruit, develop and run as an agent a Canadian citizen who has been a prominent journalist in this country for over three decades. His code name in these KGB files was “Stuart”; his recruiter, handler and paymaster over the period discussed here, from 1982 to 1990, was another agent, code-named “Ivan”. Some of the world's leading experts on KGB documents have attested to their authenticity. […] These documents illustrate the challenge our democracies face. For decades, Moscow has been recruiting and paying policy-makers, influencers, politicians, journalists and others to act as their proxies, to undermine trust in our institutions, to dissipate our political will. […]

You will see in the documents that he is named there very clearly in cursive handwriting as “David Pugliese”, who has been working as a journalist in Canada ever since.

It was lucky my face was not broadcast at that moment and that my microphone was muted, because I was visibly awestruck.

To those unfamiliar with the name: David Pugliese has been one of Canada’s most prominent defense reporters for decades, mostly for the Ottawa Citizen (now the Postmedia chain.) I count myself as a fan of his work, even if I often viscerally disagree with some of his opinions.

As shocked as I was to hear it said aloud at a committee hearing, I was not the first time I’d heard the allegation. I bit my tongue at the committee hearing and, instead, spent the weekend making some phonecalls. Now, I think I have some useful information to add.

The TL/DR is this: The allegation that David Pugliese is a Russian asset has floated around Ottawa for about a decade — often with various degrees of evidence behind it. It was in recent years that these documents, which appear to be real and which were furnished by Kyiv, were sent to Canadian intelligence agencies and were seriously investigated. While Pugliese has proved himself to be a willing customer for Russian disinformation, and while I believe he hasn’t appropriately disclosed his relationship with the Russian embassy, the idea that he is a paid agent of the Russian government is probably false.

But recent Kremlin influence operations have blurred the lines between asset and useful idiot. They invite us to, as I said repeatedly during my statement at committee, get serious.

Years ago, I received a message from a contact of mine in the Department of National Defence in Ottawa, asking for an off-the-record meeting.

At an isolated table at the far end of an unpleasant subterranean food court, I sat down. These meetings, normally, involve a download of information from government to journalist. In this case, however, the two defense staffers — there at the behest of a senior defense official — had a question.

Do you think, they asked, that David Pugliese is a Russian asset?

I laughed.

Pugliese is not a household name, unless you follow the Canadian military, but he’s been reporting on the Canadian Armed Forces since 1982. A lot of that reporting has been incredibly impactful and influential. He has aggressively covered the Canadian military’s perpetually-bungled procurement processes, dug into harassment and sexual misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces, and advocated for veterans forgotten by the military. There is little doubt that Pugliese, some years ago, upgraded from merely being a beat reporter to being a full-time critic of the Canadian military.

That isn’t a problem, per se. Some of these pugnacious beat reporters can serve as external watchdogs, becoming a conduit for all manner of grievance and complaint that isn’t otherwise being heard or heeded — rightly or wrongly.

But, in recent years, Pugliese has also become obsessed with topics that map well onto Russian talking points. Intoning, for example, that the Ukrainian community is rife with Nazis, that Canada is training neo-Nazis in Ukraine, that the Canadian Armed Forces are bankrupting themselves to help Kyiv, that Canada is being dragged into world war, and that military aid is reckless and irresponsible. In particular, he has often promoted writing from his longtime colleague Scott Taylor. If Pugliese is a Ukraine skeptic, Taylor is outright pro-Russian.

This trend was not lost on me. Nor was the fact that Pugliese’s reporting seemed to correlate closely with the stories that the Russian embassy was pushing to me at the same time. Pugliese occasionally cited Kirill Kalinin, the Russian embassy’s media flack (who was responsible for the embassy’s influence operations.) It seemed to me, however, that there were instances where Pugliese was speaking to the embassy and not disclosing it.

Take, for example, the saga around then-Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland.

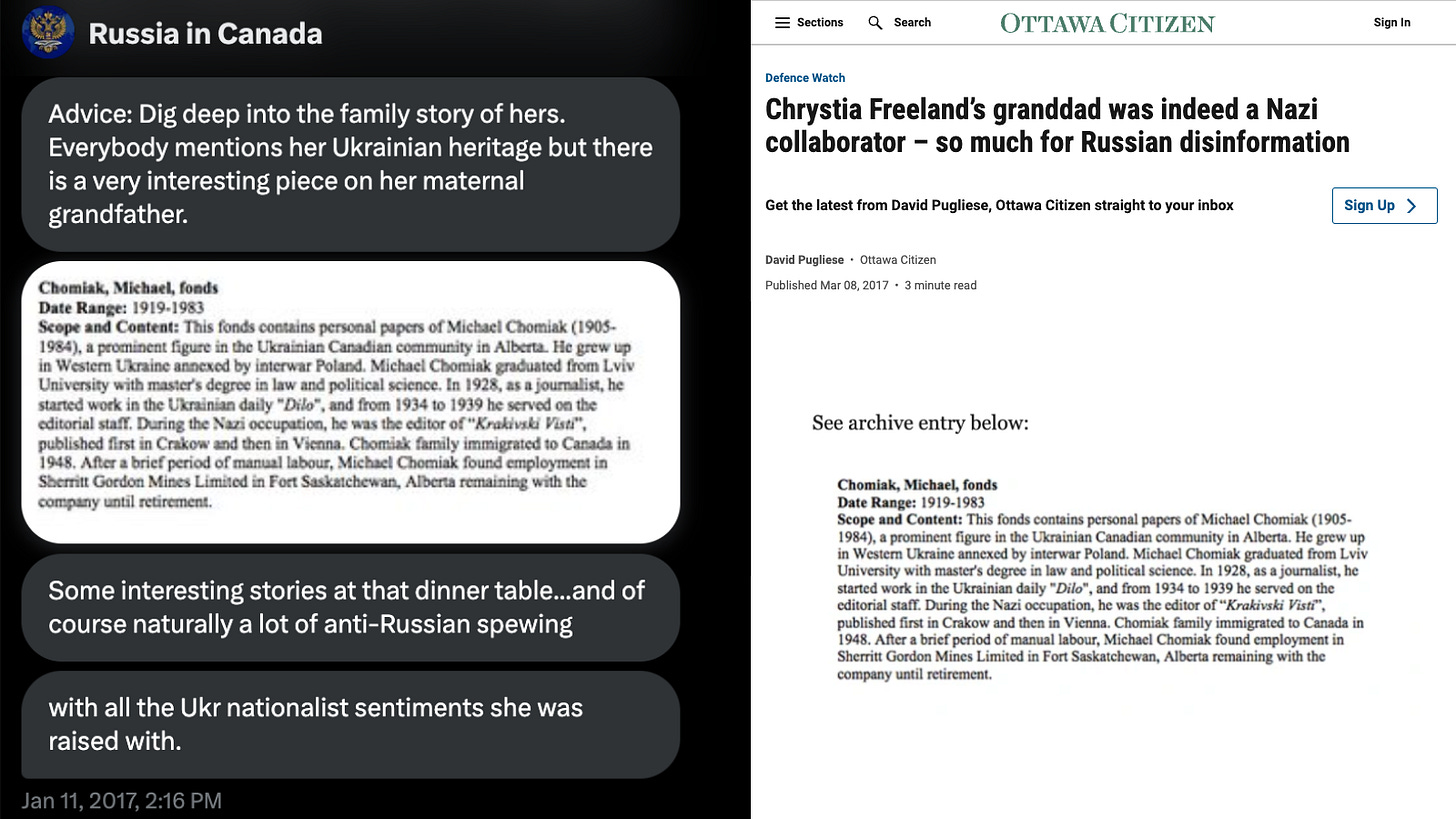

As I’ve written and I explained to the committee, we know for a fact that this story was being shopped by the Russian embassy before it was picked up by a network of shady Kremlin-loyal blogs, which precipitated its explosion into the mainstream.

In person and then via Twitter DM, Kalinin suggested I dig into Freeland’s family tree. He suggested I check out a box of files in the Alberta archives and consult the website of the Los Angeles Holocaust Museum.

Three months later, in March, 2017, Pugliese writes a piece citing those same sources. He sarcastically concludes: “So much for Russian disinformation.”

Nowhere in his story does Pugliese mention speaking to the Russian embassy for the story. And I have good reason to think he did — because Pugliese uses the identical screenshot that the embassy had sent to me nearly three months earlier. See below:

But maybe that’s all a coincidence. Or, at worst, it shows that Pugliese was happy to keep his Russian source confidential. Given Pugliese didn’t even break the story, but only reported on it after it became news, it would be quite a leap to suggest that this proves he’s a Russian asset.

The Department of Defence’s suspicions around Pugliese went much wider than this one story. They fumed at Pugliese’s uncharitable coverage and suspected that there must be another game afoot. Their case was somewhat compelling.

But what I told them, then, is still, roughly, what I believe now: Pugliese, like many self-styled critical thinkers, believes everyone trades in propaganda. He sees both the Russian embassy and the Canadian Armed Forces as corrupt and untrustworthy, therefore he’s equally likely to listen to either, depending on what they say. He trusts his own ability to suss out lies and propaganda, and doesn’t need to be lectured on who is trustworthy and who isn’t.

I think that’s woefully naive, and that’s where Pugliese and I diverge. But it still makes Pugliese a journalist. That’s in contrast to someone like, say, Scott Taylor, who jaunts off to Moscow to attend the Kremlin’s wartime dog-and-pony show, publishes Russian propaganda happily, and who play chummy hockey tournaments with the Russian embassy.

In 2023, Ukraine declared Pugliese an “undesirable person,” accusing him not of being an asset, but instead of being an “activist” shilling for Russia — much as Glenn Greenwald and Tucker Carlson have been doing for years.

Then came Thursday’s committee hearing. That’s when Alexander tabled these documents:

I received the documents independently of Alexander and I obtained the copies he filed with the House of Commons. The documents, if real, reveal that the Ukrainian office of the KGB looked at Pugliese as a “possible operative.”3

According to the documents, an KGB officer, codenamed Ivan, first met Pugliese, codename Stuart, at a lecture on the USSR’s invasion of Afghanistan in the early 1980s. Pugliese, the records say, indicated to Ivan he was left-wing and sympathetic to the Soviet Union.

The documents were produced by the Kyiv detachment of the KGB’s Directorate S, which managed the “illegals” — Soviet sleeper agents living undercover in NATO countries.

“The foreigner is to be made the subject of a series of operational agent measures aimed at additional study and verification of his potential use in the interests of Directorate ‘S',” the documents note. That included plans to better study Pugliese’s interests, politics, motivations, and to investigate whether his friends and colleagues might also be fellow travellers.

As the head of Directorate S in Moscow wrote to his Ukrainian underling, Ivan’s boss, in April, 1990:

We agree with your proposal pertaining to undertake a series of operative agency measures for additional study and verification of "Stuart" in execution of individual tasks.

The proposed presence of "Stuart" at the meeting in August of this year, in our view, should be productively used to clarify his work duties, prospects for promotion at work, material situation, personal plans, attitude towards the USSR; to establish a potential foundation for attracting the foreigner to cooperate with us; to clarify his political views, personal and moral traits; to reveal his strong and weak sides, hobbies/passions; to strengthen relations between him and the agent of the Ukrainian KGB "Ivan".

Over that year, Ivan reported spending $600 on Pugliese’s recruitment — though the ledger reports it was spent by Ivan only for “work on the case.”

For all this talk about running Pugliese, nothing in these documents indicate that he ever accepted, or was even aware that he was being targeted by the KGB. Pugliese may have been been completely unaware — or, alternatively, fully aware that his newfound Russian friend was trying to recruit him.

In recent days, I’ve spoken with a number of sources from the Canadian intelligence and defense community. What I’ve pieced together is this:

These documents were likely sent by the Ukrainian government to Ottawa sometime in the past year or two. They appear to be quite authentic, and had been sitting in KGB archives in Kyiv for decades. The documents were investigated by Canadian intelligence, but they deemed the documents insufficient to warrant a full investigation — particularly into a journalist. One former senior intelligence official tells me they were unaware of these allegations, suggesting that this report didn’t make it up very high. I’m told that there are more documents, on top of those filed by Alexander last week, but they are unlikely to shed much more light on the situation.

One of the reasons the intelligence community was so dismissive of these documents, I’m told, is because it is entirely in keeping with KGB tradecraft that they would try and recruit any and all left-leaning student-activist-cum-journalist in Ottawa. That absolutely does not mean they succeeded. Nor does it mean that Pugliese, had he been successfully recruited, kept up his cooperation into present day.

To put a fine point on this: Given I had two in-person meetings with a Russian diplomat, who was absolutely conducting information operations in Ottawa, there’s good odds that an SVR (the KGB’s successor) has a file on me somewhere, sussing out my likelihood of cooperating with their disinformation work.

Also worth noting that this operation was run less than a year before the Soviet Union began dissolving, precipitating Ukraine’s split from Moscow and the divorce inside the KGB. It seems likely that this operation was interrupted mid-way through.

So how did these documents make their way into the public record?

It seems that these KGB records were entered into evidence as part of an ongoing libel suit between a firearms company and Pugliese. The lawsuit turns on one of Pugliese’s articles, which claimed that Ottawa-based charity Mriya Aid was wasting money destined for Ukraine.

The lawsuit, filed by a businessman who supported Mriya Aid, claims Pugliese is “a well-known Pro-Russia writer” who “regularly takes part in Pro-Russia activities, played for a Russian embassy hockey team, writes Pro-Russia content etc.” (These allegations appear to be confusing Pugliese for Scott Taylor. Pugliese claims he doesn’t play hockey and can’t skate.)

Far from serving Russian masters, Pugliese’s main sources for this story were, in fact, fervent supporters of Ukraine’s defensive effort — and who are critical of unreliable charities wasting money and shipping inferior products. (Full disclosure: Pugliese’s sources had also pitched this story to me, but I passed on it.)

Pugliese essentially confirmed the Mriya Aid connection in an interview with Canadaland. There, he gave a categorical denial of the story: “I am not a KGB agent. I haven't been a deep-covered KGB agent ever. I've never accepted any money from the Russians or anybody — but my employer, of course. It's total fabrication.”

I’m inclined to believe Pugliese on that. At most, the evidence suggests that Pugliese was the target of a KGB recruitment operation.

Beyond that, there are good indications that Pugliese may have been relying on the Russian embassy as an unnamed source, a decision I find ethically dubious, but far from traitorous.

It didn’t take much for Kostiantyn Kalashnikov and Elena Afanasyeva to, allegedly, convince Liam Donovan and Lauren Chen to ink a seven-figure deal.

Kalashnikov and Afanasyeva were employees of Russia Today, Moscow’s primary global propaganda arm — an arm which had, since the start of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, been largely cut off from the West.

Using a flimsy cover, the Russian propagandists approached Chen and Donovan, the two Canadians behind Tenet Media, a little-known talent agency for far-right influencers, grievance peddlers, grifters, and conspiracy theorists. Their so-called talent included Tim Pool, Dave Rubin, Benny Johnson, Lauren Southern, and others.

As part of the deal, the RT propagandists allegedly fed the Americans and Canadians story ideas, used them to build up a right-wing broadcast channel, and even edited their videos to ensure the Russian line came through nice and clear. For it, the alleged patsies were paid millions of dollars.

We know all this — including the detail that, when payment was delayed, the Tenet founders googled “time in Moscow” — because the Department of Justice filed these particulars when Kalashnikov and Afanasyeva were indicted.

We call these detailed legal documents, which lay out in great specificity the crimes alleged to have been committed, “speaking indictments.” While the Department of Justice may still redact sensitive or classified material from these indictments, they have proven remarkably useful in recent years. We know the extent of India’s and Iran’s assassination plots on American soil and the breadth of Donald Trump’s attempt to overturn the 2020 election because of these speaking indictments.

I’ve written in the past about how these indictments can actually be used as a defensive tool against foreign meddling and malign information operations, and my testimony last week was very much on this theme.

In most other jurisdictions, the process is exactly the opposite. Had Chen and Donovan been indicted in their native Canada, for example, their arrests would have provoked just a trickle of information — the charges and perhaps, but not necessarily, the foreign government they are accused of collaborating with. The breadth of the allegations would not be allowed to fully emerge until trial: Even then, critical details might still be classified or withheld. (We are still in the dark about some of the actions of a high-level double-agent who was arrested five years ago.)

This reticence to release information usually turns on two concerns: That disclosing evidence could prejudice the outcome of a trial or harm the prosecution’s case; and that it would require disclosing the sources and methods intelligence services use to compile information.

But, as the Americans show, disclosing details of these plots can be very disruptive. And sometimes disruption is more effective than prosecution. Kalashnikov and Afanasyeva are, of course, still in Russia and are unlikely to ever see the inside of an American courtroom, ditto for the alleged India thugs and their puppetmasters.

The Department of Justice’s disclosure in the RT case effectively killed Tenet Media, and exposed these influencers for the charlatans, rubes, and hypocrites they are. Tim Pool, long one of the most gullible members of the uber-online far-right, recently announced his possible retirement from being a professional useful idiot. (We’ll see how long that lasts.)

Canada’s disclosures around New Delhi’s campaign of terror, meanwhile, have been a really important (albeit insufficient) rebuke of Narendra Modi’s tactics.

But these allegations need to be made carefully, and with credible evidence.

Earlier this month, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau casually mentioned that Jordan B. Peterson and Tucker Carlson are funded by Russia. Making such an allegation without evidence or explanation, and failing to retract or clarify, is extremely stupid, reckless, and damaging. (I strongly suspect that the prime minister confused some high-profile right-wing trolls with some of the lower-profile right-wing trolls.)

Turning back to Thursday’s committee hearing, Alexander made a lot of big allegations: He alleged that the 2022 Freedom Convoy “had all the hallmarks of Russian influence,” that Moscow may have equally meddled in support of “the yellow vest movement, the [far-right People’s Party of Canada] PPC, [Western separatist party] Wexit, the anti-vax movements, pro-Hamas protests,” and, of course, that the Kremlin was running Pugliese.

I tend to disagree with Alexander on all those points. I think the role of Russian media and foreign influence operations on those events and groups was and has been, at best, marginal. The commission struck to study the Freedom Convoy tends to agree, finding that funding from outside of North America was negligible and, citing government intelligence, that there was “no evidence of foreign disinformation campaigns related to the convoy itself.”

In the same way that we ought to proactively disclose evidence of foreign influence operations here, we need to be careful not to make hasty and rash allegations based on insufficient evidence. In all cases, we should let the evidence to do the talking, or else we’ll wind up shadowboxing, growing more distrustful and paranoid. Then, we’ll be doing our adversaries’ work for them.

Yes, some instances of foreign meddling involve million-dollar payments and a clear paper trail. But lots of clandestine work falls into a gray zone.

Kirill Kalinin was so impactful because he made real relations with journalists, designed to insert the Kremlin’s viewpoint into our national discourse. He didn’t need to pay off journalists or recruit assets. Kalinin’s impact was far more clever: He convinced journalists in Ottawa that they were managing the embassy, when in fact the embassy was managing them.

The cut-and-dried examples where Russians are conducting subterfuge, or where Westerners are taking rubles to spread lies, are easy to call out. Useful idiots are harder to pin down.

And there can be no greater useful idiot than Elon Musk.

And, as the Wall Street Journal reported last week, it was Vladimir Putin himself who groomed the world’s richest man to become a useful patsy for Moscow’s foreign policy ambitions. As the Journal reports:

In October 2022, Musk said publicly that he had spoken only once to Putin. He said on X that the conversation was about space, and that it occurred around April 2021.

But more conversations have followed, including dialogues with other high-ranking Russian officials past 2022 and into this year. One of the officials was Sergei Kiriyenko, Putin’s first deputy chief of staff, two of the officials said. What the two talked about isn’t clear.

Last month, the U.S. Justice Department said in an affidavit that Kiriyenko had created some 30 internet domains to spread Russian disinformation, including on Musk’s X, where it was meant to erode support for Ukraine and manipulate American voters ahead of the presidential election.

If evidence exists implicating Musk conspiring with Russia, we should see it.

That’s it for this week, thanks for reading!

In the Toronto Star this week, I’ve got a deep dive into the much-promised never-delivered maybe-high-speed rail project that could make us a country again. (No pressure.)

In Foreign Policy, I wrote that it’s time for Canada’s allies to step up and make an example of India’s assassination games.

I’ll be back sooner than later with some final thoughts ahead of next week’s presidential election. (😬)

Dark Days in the Newsroom: McCarthyism Aimed at the Press, Edward Alwood (2007)

Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America, John Earl Haynes, Harvey Kleh (2000)

These translations come from the Parliament of Canada, though I’ve doublechecked the translation where possible.

Really good article. Thanks for being a voice of reason and sanity in a sea of chaos.

I can attest to the ubiquitous Soviet friends active in Ottawa in the 1980s. As a left-wing Carleton social sciences undergraduate in the 1980s, the invitations to discussion sessions and coffee parties were plentiful. We were undergrads so the "idiots" goes without saying; "useful," for the most of us definitely not. Actually, given my lack of money at the time, I would have appreciated some sort of Soviet pay-off ;-) We used to joke about it.