Radio X Rules the Nation (Québécois)

How one plucky and pornographic talk radio station in Quebec City redefine a nation's politics — and what it can tell us about our current mess. Plus: Who blew up Nord Stream?

It’s July 22, 2004, and 50,000 pissed off radio fans are marching through Quebec City.

A week earlier, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission had opted not to renew CHOI-FM’s license, forcing them off the air. “The spoken word content aired on CHOI-FM,” they wrote, “leave the Commission with few options.”

The Canadian radio regulator had been inundated with complaints. One letter-writer noted that the morning show hosts seemed "incapable of refraining from asking every female caller how big her chest is.” (Whomst amongst us, really.)

At all hours of the day, the station — known more commonly as Radio X — was downright pornographic.

This being the era of Howard Stern, maybe some lewd drive-time radio could be forgiven, even by the stuffy Canadian censors. But Radio X was carving out a new, particularly virile, brand of racism on the airwaves.

One host, André Arthur, called students studying in Quebec who hailed from Africa “cannibals.” Their most famous host, Jeff Fillon, suggested that patients in psychiatric hospitals should be gassed because they were a drain on society.

The thing is, it was also wildly popular. The Commission’s ruling prompted those tens of thousands of people to take to the street, marching on the provincial parliament, demanding their favorite radio station’s return to the airwaves.

And it worked: The federal government gave Radio X permission to continue broadcasting as they duked it out in court. In the ensuing legal drama, the station lost and was slated to go off the air in 2005. A last-minute reprieve came by way of a new owner who swooped in to purchase the station. Because they obtained a new license for Radio X, the regulate’s decision was moot.

And so Radio X carried on: Ostensibly, as a rock station but, really, as a home for right-wing shock jocks.

This week, on Bug-eyed and Shameless, the story of Radio X: How a few blowhards can help forge a miserable political climate. As Quebecers go to the polls on Monday, this history has never felt so relevant.

And for subscribers: We play a game of Nordstream whodunnit.

“The bag of halal [chicken] wings that is sold at [grocery store] Maxi, each sale, they send over to terrorist groups,” one Radio X host declared in 2012. “This isn’t a joke, this isn’t science fiction, this isn’t like James Bond, this is reality.”

Quebec, like plenty of jurisdictions in North America, saw a massive growth in migration from countries that it previously hadn’t received migrants from before. In 1991, the province had under 50,000 Muslims — less than 1% of its population. A decade later, that number had doubled. A decade after that, it more than doubled. By 2011, 3% of Quebec reported Islam as their religion.

You’d be hard-pressed to describe a negative outcome from that influx of new immigrants. Both in the major cities and in les regions, Quebec’s Muslim community is thriving, and the whole nation is better for it.

But as was seen virtually everywhere across North America and Europe through the 2000s and 2010s, a growing Muslim, Arab, and non-white population was cause for some tremendous anxiety. That anxiety was, unsurprisingly, higher in places that had media outlets willing to go there.

And Radio X went there. A lot.

“Europe is now invaded by Islam,” one Radio X host said in 2012, calling the entire religion “a problem.” Over the years, hosts would conclude that Islam is “founded on terror and violence.” Another guest remarked on “the relationship that exists between terrorism and multiculturalism.”

Their bug-eyed crusade against Halal meat continued as well, with one official Radio X Facebook account snapping photos from a local grocery story of a Halal meat freezer, sarcastically tagging it “#toutvabien” (everything is fine.)

Radio X full-scale meat meltdown quickly prompted the notionally left-wing sovereigntist Parti Quebecois to begin claiming that halal meat was “against Quebec values.”

Soon they’d develop a new target: Women who wear the veil.

“If you arrive in a credit union and a veiled woman approaches you, you say ‘no!’” A former professor and frequent Radio X guest ranted. “‘What you’re wearing hurts my fundamental rights, your veil, it profoundly shocks me. You’re a racist, you’re intolerant. I want to be served by somebody else.’” (For good measure, he did admonish Halal meat being served in his university cafeteria as “an aberration.”)

The professor summed up what could have been a tagline for Radio X at the time: “Yes, Islamophobia is legitimate.”

It’s worth noting just how popular this station was. For a time, Radio X boasted north of 400,000 daily listeners. That number dropped closer to 100,000 in the 2010s, but that nevertheless meant that upwards of 1% of the province listened to Radio X. Not bad, considering the station ostensibly doesn’t stretch beyond Quebec City and its suburbs.

What’s more, some of the station’s most odious and controversial hosts were lured away to competitor stations, precisely because of their edgy appeal, slowly infecting the entire radio market. One host, Arthur — who called foreign students “cannibals” — was elected to the House of Commons as an independent, which is a particularly uncommon feat in Canadian politics.

I don’t want to make it sound like Radio X was a singular ideological influence on Quebec — it wasn’t. Quebec newspapers and TV shows certainly had their fair share of racist nonsense.

Quebec also has a particular set of anxieties around religion: An intense fight to secularize the nation, and get it out from under heel of the Catholic church, has enshrined the idea that Quebec needs to have not just freedom of religion but freedom from religion. To inform that, it has imported the idea of laïcité from France: The idea that individuals carrying out functions of the state should remain ‘neutral,’ in the sense that they must have no religious identifiers visible.

So Radio X didn’t create any of this nonsense, per se. But it was remarkably effective at incubating, prolonging, and popularizing this tripe.

Radio X’s fixation on the veil — whether it was a hijab, niqab, burqa, chador; they rarely bothered to learn the difference — became a core trope of the station. “A veil is not a religious symbol like the cross,” a guest told Radio X listeners.

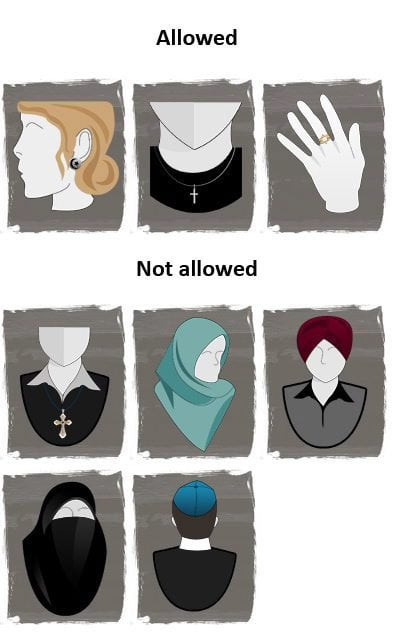

The Parti Quebecois had been elected to government in 2012. A year later, they tabled the euphemistically-titled Charte des Valeurs Québécoises. In it, the government sought to ban a raft of public sector workers from wearing religious symbols. This dystopian infographic illustrates the insanity fairly well.

While the official line was that banning these religious symbols was about preserving the neutrality of the state, Radio X provided the kind of clash of civilizations paranoia that helped add fuel to the debate. In September 2013, just months after the Charter was tabled, listeners heard that there are “good Muslims” and there are “bad Muslims.” And those bad Muslims? “There’s an agenda. They want to impose their religion on us. Yes, they want to dominate the world.” And that plan “infringes on our fundamental values.” How does the host know this? “I meet a lot of Muslims, often because I take taxis a lot.”

Over the years, one host became a particularly vociferous voice on the network: Eric Duhaime.

“Islam is a religion that is against Jews, Buddhists, Christiains,” Duhaime lamented on the airwaves in 2015. He bemoaned that so many of Quebec’s immigrants came from the Maghreb region. “It’s immigration that has been a failure,” he lamented, with no evidence beyond a sweeping statement that those Muslims don’t learn French. “A good Muslim, that doesn’t exist,” he said.

I won’t subject you to every racist utterance made on Radio X in those following years. The Charte des Valeurs, initially supported by a majority of the Quebec population, eventually became politically toxic. It became so linked with demonizing religious minorities and immigrants that its authors were turfed out of office. Their successor essentially shelved plans to restrict religious symbols in the workplace.

In the interim, however, the militant far-right began flexing its muscle. Groups like La Meute (“the wolfpack”), Storm Alliance, and Atalante began to hold anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant demonstrations. Their members ranged from basic Islamophobes to outright white supremacists and actual neo-Nazis. Some would face charges over the years for various violent threats against politicians. And Radio X was downright fond of them.

“At the end of the day, we can raise our hats [to La Meute],” Eric Duhaime told listeners in 2017. He celebrated a recent demonstration of theirs, and clicked his tongue at the real enemy: “Those who went overboard, it was the counter-protesters. It’s bizarre, because those who we today accuse of being fascists, it’s them who carry themselves better. It’s the anti-fascists who have the air of being a totalitarian gang who want to force everyone in the world to express their opinion.”

Bernard Drainville, his co-host and the former Parti Québécois minister who introduced the Charte des Valeurs, agreed, concluding that “the majority of Muslims” probably agreed with La Meute. It was the Justin Trudeau in Ottawa, he said, who was the real problem. (A member of Trudeau’s government had just tabled a motion condemning Islamophobia.) “They’re in the process of using the Muslim community for their own political ends,” Drainville concluded, without a whiff of irony. (As Steve Faguy points out, the Duhaime-Drainville show was actually on FM93 — not actually Radio X. My bad! Even still, it illustrates the Radio X-ification of radio in Quebec.)

Plenty of places across the Western world fell into a deep paranoia about Islam over those years. The real threat of the Islamic State, faux-intellectuals pontificating about the very nature of Islam, and the perceived ‘Islamification’ of major cities — it all drove this burgeoning Islamophobia. But some media markets exploited that more than others. Fox News, the British tabloids, right-wing talk radio: All contributed to this pervasive anxiety.

Radio X serves as a particularly stark example.

And it had deadly results. In January 2017, 27-year-old Alexandre Bissonnette walked into a Quebec City mosque, equipped with a semi-automatic rifle and a handgun, and murdered six worshippers. While we have no idea if he actively listened to Radio X, it’s hard to divorce the intense hatred he harbored for immigrants and Muslims from the climate that Radio X helped foster in Quebec.

In 2018, after a relatively successful four-year mandate, the Quebec government — led by the centre-to-centre-right Liberal Party — sought a second turn. Their main competitor was not the ostensibly-progressive stylings of the anti-Islam Parti Quebecois, but instead the populist right-wing Coalition Avenir Quebec, led by François Legault.

Legault ran a campaign that played to that paranoia. He promised to reduce immigration, advance an even-harsher Charte des Valeurs, and force immigrants to take a ‘values test’ before coming to Quebec.

The CAQ and Legault won handily.

When Legault followed through on his promise and tabled Bill 21, to ban a massive number of public sector workers from wearing religious symbols — teachers who wear the hijab, cops who wear a turban, judges who sport the kippah — Radio X rejoiced. (So did La Meute.)

A series of street protests cropped up in 2019. One protester summed up the corrosive hypocrisy of the government. “It’s scandalous that the same politicians who deplored the January 2017 massacre are now putting in place laws that will put Muslim lives in danger.”

To that, Radio X host Dominic Maurais said “if you hate Quebec that much, go away!”

That’s essentially the line that Legault himself took. The premier has declared, upon the lightest whiff of criticism of his racist law, “the Quebec nation is under attack!”

When the pandemic struck, Radio X became an incubator for that obscene misinformation as well.

“It’s a respiratory virus that attacks old people and overweight people and those who have problems like diabetes…luckily, unlike influenza, it doesn’t touch infants,” host Jean-François Fillion ranted, incorrectly. He called it the “COVID show.” When businesses reopened illegally, despite public health orders shutting them down, Radio X celebrated their bravery. One such business, a Quebec City gym, caused hundreds of COVID-19 cases and at least one death with their lax policies in the height of the pandemic.

A senior public health official went so far as to point the finger at Radio X for people ignoring public health advice: “My perception is that, yes, it plays a role. It creates a culture which says that if it comes from the government it’s always bad.”

Radio X became a home for anti-vaxxers as well, including Youtuber David Frei, who claimed on the air that the vaccines were “experimental,” that children shouldn’t be vaccinated, and that the Canadian government was breaching the Nuremberg Code. Frei would go on to be an influential streamer during the anti-vaccine occupation in Ottawa.

The station’s influence has been felt extensively over the years. Quebec City’s enormously popular former mayor had boycotted Radio X, due its toxic influence. When he retired, he tried to pass the torch to his protegé — instead, voters opted for Bruno Marchand, who had promised to end the Radio X boycott. Despite criticism, Marchand used city money to take out ads on the notorious station.

Legault, meanwhile, is on track to win an unprecedented majority of seats in next week’s provincial election. Running with him is Bernard Dranville, the architect of the Charte des Valeurs, turned Radio X host. Also running is Dranville’s former co-host, Eric Duhaime — for the far-right Quebec Conservative Party. Duhaime, who has tried to shed some of his past comments, also wants harsh limits on immigration and maybe even a wall along the southern border.

The last decade in la belle province is a microcosm for how the media can foster and weaponize paranoia on a grand scale. These ideas — that Halal meat is contrary to our values, that women who wear the veil are either a danger or in need of saving, that Islam presents an existential threat to our society — they don’t come out of nowhere. They don’t grow by themselves. Human beings are racist and anxious by design, but it takes work to get them ascribing to grandiose conspiracy theories like these.

As I wrote in B-EAS #17, trying to regulate this problem away isn’t going to work. I don’t believe Quebec would be better off if the CRTC had successfully knocked the network off the air in 2004.

And radio is something that we, in theory, can regulate. These stations are using public infrastructure to spew their nonsense. The internet has intensified this radicalizing influence and it sits even further from the reach of individual governments.

The best thing we can do is identify these narratives, understand them, and confront them. There have been those in Quebec who have been doing exactly that for more than a decade: Sortons les Radios-Poubelles has been keeping an eye on Radio X since 2012. (I relied on them heavily for this post.)

Left ignored, you suddenly might find yourself living in a state that tells women how to dress in the workplace, which demonizes immigrants as immoral, and where Eric Duhaime is seeking high office.

If you want more Quebec election content, check out my column in the Globe & Mail.

And if you’re looking for a long-read about the future of the internet, I’m in WIRED this week talking about the most important UN body you’ve never heard of.

Below the paywall: The curious case of the exploding pipeline.

As you’ve undoubtedly seen by now, the underwater pipeline connecting Russian gas to Europe went boom recently.

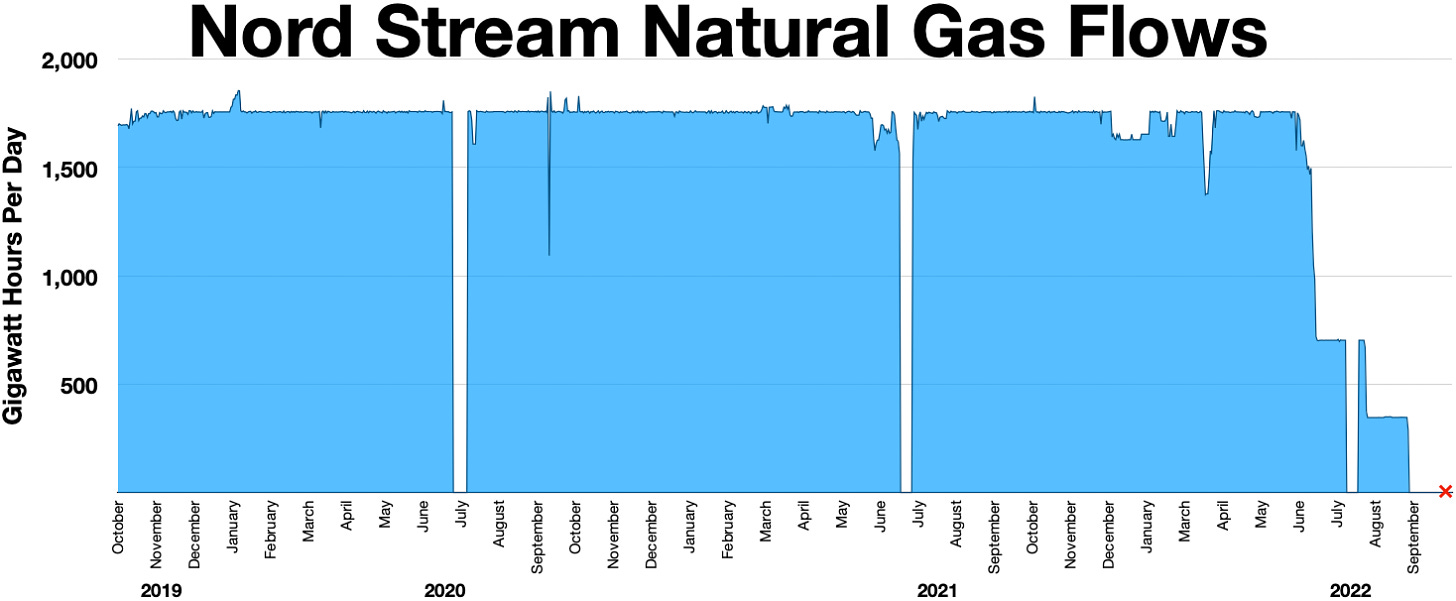

The pipeline has been one of the most fraught parts of the Russo-European uncoupling over recent months. The OG Nord Stream began pumping Russian gas to Germany in 2011, pumping roughly half of Europe’s total imported gas. Its capacity was supposed to be doubled, thanks to the planned Nord Stream 2. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine earlier this year, however, killed the project for good.

In the ensuing tit-for-tat, Russia began throttling the pipeline’s outflow — insisting a variety of technical problems stopped them from sending gas into Europe. They even lamented that turbines held up in Canada, frozen by sanctions, prevented them from being able to run the pipeline at capacity. When I joined the Cold Front podcast in August, amid that chaos, I predicted that Moscow and its puppets at Gazprom weren’t terribly interested in actually resuming gas exports, but were more keen to freeze out Europe. In the days after that interview, Gazprom refused to accept the Canadian turbines and subsequently shut down the pipeline entirely.

Which brings us to September. Nord Stream 1 is offline indefinitely, Nord Stream 2 is dead. Gas prices are skyrocketing in Europe, causing further populist ruptures across the continent. And suddenly, Nord Stream blows up.

Accusations flew in every direction. Pro-Kremlin Telegram channels suggested that American underwater drones had committed the sabotage — and within a day, Moscow was preparing a dossier to table at the United Nations to blame the West. The West and Ukraine, of course, are blaming Russia.

So, whodunnit?

For starters, it’s worth noting that this isn’t the first time someone tried to blow up Nord Stream.

In 2015, the Nord Stream discovered an unmanned underwater vehicle armed with an explosive charge — normally used to clear mines. While it’s unclear if the drone was placed there intentionally, or whether it was abandoned, the Swedish Armed Forces nevertheless had to be called in to neutralize the threat.

The underwater drone was discovered roughly 100ish miles from where the explosion likely occurred this month.

There were a few other indicators that this was coming.

The same day of the explosions, the Ukrainian cyber agency put out a bulletin warning that “the Kremlin plans to carry out massive cyberattacks on critical infrastructure facilities of Ukrainian enterprises and critical infrastructure institutions of Ukraine's allies. First of all, the blow will be aimed at enterprises of the energy sector.” (Rough translation.)

The Ukrainian government has gone mum about that bulletin in the days since the attack on Nord Stream.

Der Spiegel has also reported that the CIA was warning Germany of a possible attack on its pipelines throughout the summer.

It may seem like the act of a madman to blow up your own pipeline, but sometimes punching yourself in the face is the best way to intimidate your adversary without starting a fight. If Europe believes Putin is willing to torpedo other pipelines — like, say, the Baltic Pipe which began moving natural gas from Norway to Poland, which began operations on the day after the Nord Stream explosion, September 27 — perhaps it will lean on Ukraine to accept an otherwise untenable peace deal. Or, at the very least, maybe it will paralyze Europe with political chaos.

Putting aside the geopolitics for a second: This explosion is great news for Russia. As Moscow clearly planned on keeping the pipeline shut indefinitely, the mounting legal risks for operator Gazprom were stark. While plenty of Russian assets are frozen right now, Europe hasn’t generally moved to seize or liquidate them. If Russia kept its pipeline shut, with little legitimate basis, that was likely to change. A sudden explosion means Gazprom can claim an act of god, and abandon its obligations to deliver gas to Europe without facing the same financial consequences.

Energy analyst Sergey Vakulenko makes this point well:

One irony of the attack is that Russia’s Gazprom potentially stands to benefit: it will no longer need to invent excuses not to supply Europe via Nord Stream 1. Now it can claim a force majeure, which will dramatically reduce the risk of compensation claims for non-delivered volumes. This logic, however, does not explain the damage caused to Nord Stream 2. On the other hand, the Nord Stream consortium companies and eventually Gazprom might even hope to collect some insurance for the damaged pipelines. Given that they already looked set to become a stranded asset, that would be far from the worst outcome for the giant company.

I suspect we’ll see a formal attribution to Russia, by NATO, in the near future. Whether or not they can really back up that attribution with clear evidence remains to be seen.

Until next week!