Nothing Is Sincere, and Everything Hurts

How troll politics are setting up an unreal era

When Vladimir Putin suddenly became the second president of the Russian Federation, on the eve of the millennium, he was a virtual unknown to the Russian public.

The more he appeared on their television screens, however, the more they started to recognize him.

There he was, practising Judo. There’s him shirtless riding horseback through the forest. He was exceedingly well read and spoke multiple languages, but comported himself with the stoicism of a former spy. Unlike the fat Communist officials who dragged themselves from the Kremlin to the pub, Putin exuded a rugged kind of self-sufficiency to which the Russian public aspired.

The self-interested West wondered if Putin was making himself into a Hollywood movie star or some kind of slavic cowboy. Russians, however, finally made the connection: Our president is Erast Fandorin.

It was a strange impulse. Erast Fandorin is a literary character, a detective par excellence, on par with Sherlock Holmes. His story plays out in Tsarist Russia in the twilight of the 19th century, in a period of sudden liberalism at the end of an era. He, like Putin, was a well-built master of eastern martial arts. He was a polyglot, and was well-versed in palace intrigue. He pursued radicals, both leftists and conservatives, and jousted in the world of the clandestine arts. But his only loyalty was to Russia, and preserving order.

Fandorin first appeared in text in 1998, just as Putin was rising from the murky underworld of Russian politics to lead the state. Fandorin was “a private hero for a privatized nation,” American writer Leon Aron wrote at the time.1 The sleuth-detective-spy was unbelievably popular, selling tens of millions of copies across its 18-book run, the most recent arriving in 2018.

Author Boris Akunin (a nom de plume of Grigori Chkhartishvili) created Fandorin not just as a detective capable of solving murder and intrigue, but of being the conceptual embodiment of a new Russia. Fandorin, he explained, had traits “a national Russian character — for different political and historic reasons — has always lacked: Honorable self-restraint, privacy, and dignity.”

While Akunin made no secret of his attempt to explore Russia’s present by looking at its past, he bristled at the comparisons between the president and his protagonist.

If Putin was any character in the books, Akunin said, he was Alexander III: The reactionary and despotic tsar. In later books, the villains whom Fandorin pursued started to resemble Putin — like one political assassin who deployed an esoteric and deadly poison to kill a senior politician.

“Putin has the mindset of an adolescent,” Akunin said in 2011. He begged: “Please don’t compare him with my Fandorin.” Whatever comparisons could have been made have become absurd, he said. “The population has been maturing gradually, while Putin has stayed the same.”2

But it wasn’t the public Akunin needed to convince: It was Putin himself. Putin was, at the very least, encouraging the comparisons — and perhaps actively leaning in to the parallel between himself and the much-beloved Fandorin.

Putin was, to borrow the scholarly language, “self-fashioning.” He identified a character in the public zeitgeist, one who embodied the wants and desires of the public, and remade his public image to fit that mold. He held up a mirror, and allowed the people to see what they wanted to see.

“Putin’s self-fashioning,” Russianologist Brian James Baer writes in a lengthy comparison between the president and Fandorin, “suggests his unique individuality, an autonomy that sanctions his authoritarianism.”

This week, on a very special Bug-eyed and Shameless, a musing on self-fashioning, Donald Trump, seizing Greenland, and how leaders make themselves into something evil.

Dear Old Greenland

Donald Trump is self-fashioning himself to become a beloved figure in the American psyche: Donald Trump.

A consummate self-promoter, his whole career was about making people think he was richer, more successful, more clever than he was. In politics, Trump leveraged the airbrushed and exaggerated version of himself popularized by The Apprentice, amongst other media, to seize on the public’s imagination at a time of anxiety. He has, in many ways, been standing behind a 10-foot cardboard cutout of himself since he first entered politics nearly a decade ago.

While other politicians worked on the first level, the real world where legality and practicality matter, Trump was always good at inventing his own world and inviting people in. That worked great on the campaign, but as his first term in office showed, he was a chaotic and mercurial manager with a lack of acumen for actually governing.

Four years in exile, however, meant his fair weather advisors and fans left and only his most diehard believers remained. And Trump began self-fashioning to be what they wanted.

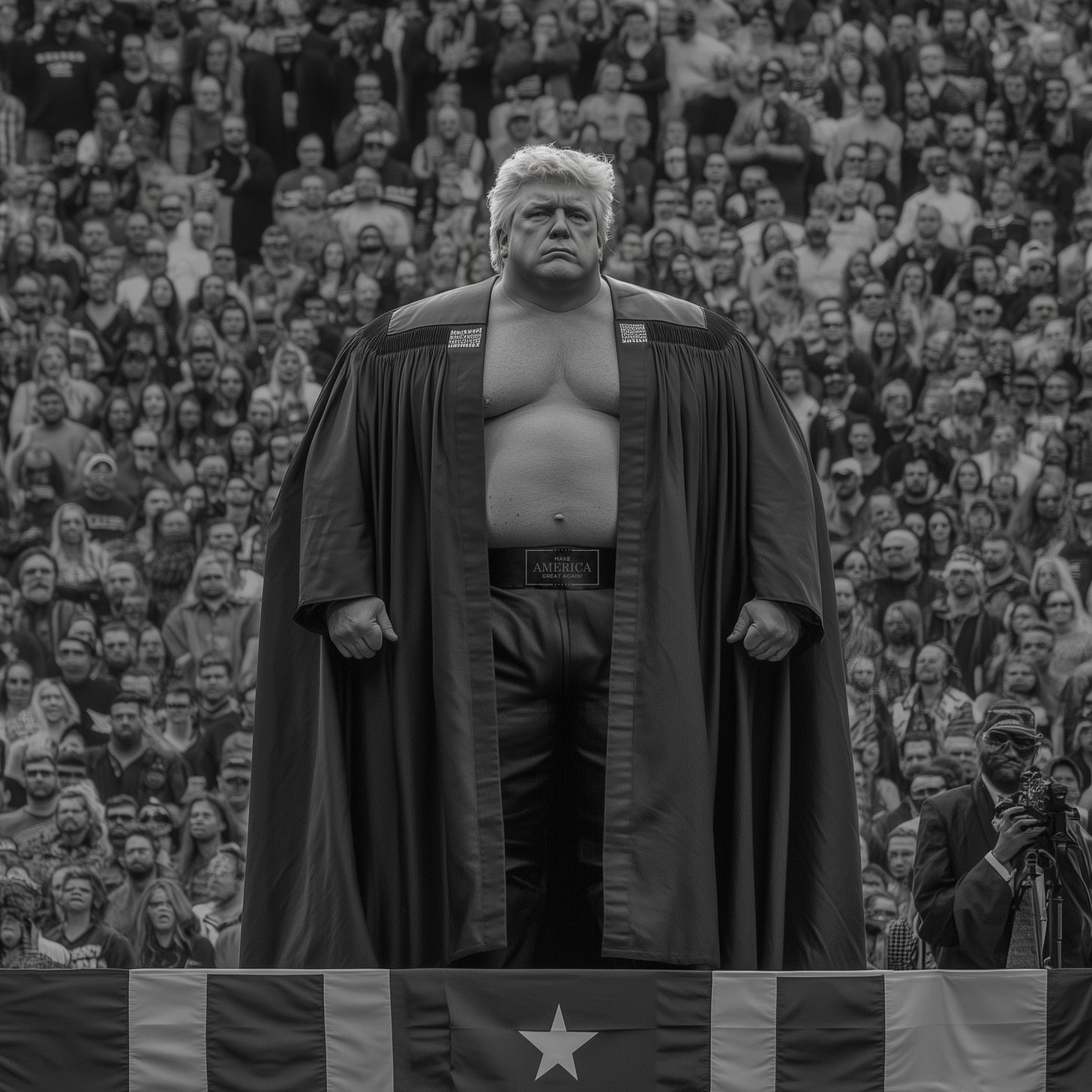

Whether it is Trump’s naked overtures to QAnon, his shimmy-shake routine for the Bitcoin bros, or echoing dehumanizing language about migrants: As the average MAGA supporter became more hardline, so did Trump. As his supporters began using AI-generated images to turn him into a larger-than-life figure, he tried to make himself into those unreal deceptions. The positive feedback loop continued right through the election.

Which brings me to Greenland.

When Trump first raised the possibility of acquiring Greenland, in his first term, his administration fumbled the question with its usual grace: Stumbling into the issue, then getting deadly serious about it, then hastily moving on to something else. Like on so many files, the Trump administration had an underlying policy concern — acquiring critical minerals and blocking China’s Arctic ambitions — but it was caked in layers of political adventurism, amateurism, delusion, paranoia, and incompetence. (And, as with those other files, it was helped along by some not-so-subtle Russian nudging.) What began as a Trumpian bit of imagination became just another issue that his administration could not follow through on.

Few imagined Trump ever reviving the issue. It was a non-starter, a distraction, a fantasy.

And then Alexander Gray, a Trump loyalist and former staffer, penned an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal relitigating the idea. In it, Gray lays out a relatively sensible position: That, should Greenland vote for independence from Denmark, it would be in America’s strategic interest to offer Nuuk a deal to head-off likely entreaties from Beijing. “The U.S. can offer an option that preserves Greenland’s sovereignty while protecting it from malign actors,” Gray writes, likening this hypothetical association to America’s arrangement with Palau and the Marshall Islands.

The op-ed itself was fairly well-argued, albeit very hypothetical. But it was his tweet that really cemented its utility as a policy idea for the Trump administration: “The foreign policy establishment can scoff,” Gray wrote, but this was an opportunity for Trump to “make his greatest deal yet.”

It pulled down the mask and made the appeal clear: This idea will help Trump become the real estate developer he plays on TV.

Shortly thereafter, Gray appeared on Steve Bannon’s War Room podcast to pitch the idea. Bannon was effusive. “Greenland is absolutely critical to [our] national security, unlike the eastern Russian-speaking border of Ukraine,” Bannon said. Less than a month later, Trump posted that owning Greenland was an “absolute necessity.” His proclamation shed all the caveats and ifs present in Gray’s op-ed and swung hard at the idea.

Even if this would be mostly theatrics for the incoming president, it fit nicely into Bannon’s paranoid worldview — that a cataclysmic confrontation with China is on the horizon. (Dispatch #121)

It wasn’t just Greenland. Never one to just play the hits, Trump was suddenly pitching a new era of Manifest Destiny: Making Canada the 51st state, seizing the Panama Canal, and who knows what else.

The world went scrambling. The various threats to Ottawa knocked over a domino that would, ultimately, led to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s resignation. It seemed to hasten the planning for Greenland’s actual independence referendum. It may yet push Panama into a closer relationship with China.

In the weeks since Trump first floated his imperial ambitions, reaction has largely fallen into three camps: The feckless appeasers, who have earnestly started the work necessary to enable this American neo-colonial empire; the panickers, who have taken these threats deadly seriously and who insist on a robust response which treats them as official American doctrine; and the skeptics, who see this as one big troll.

Here in Canada, the feckless appeasers have been well-represented by Kevin O’Leary. Little Quislings like him should be relentlessly mocked, their homes blanketed in white flags.

But the other two camps don’t have it quite right, either. The truth lies somewhere between.

The Art of the Deal

Despite the bluster, Trump returns to the White House in a fairly weak position.

He is heading into negotiations with Russia to end the Ukraine war that are set to be infinitely harder than he lets on. He is tasked with slashing enormous sums from the federal budget, and to do so he will need the help of a fractious Republican-controlled Congress prone to infighting. He’ll be fending off allegations of being a lame duck president nearly immediately, or else try and explain how he is constitutionally permitted to seek a third term. Very quickly, Trump will have to meet the sky-high expectations he set for himself.

Despite that, Trump is heading to his inauguration in total control of the narrative. If he had merely revived his talk of trade war, the discussion would be on the inflationary impacts of tariffs and the likely retaliatory measure. Instead, Trump walked out with an absurd starting position and completely up-ended the discussion. His lackeys in his loyal media were quick to take the cue, even if they were barely able to hide their grin as they pitched it.

I was on the phone this week with Ranj Pillai, Premier of the Yukon. Shortly before the new year, Pillai trekked down to North Carolina to meet Donald Trump Jr. The premier and the scion snacked on bear meat and oysters at a hunting lodge and discussed the incoming administration’s plans for the continent.

“They were all laughing,” Pillai told me, “and couldn’t even believe that media and Canadian talking heads were responding the way they were.”

This is classic Trump. Pick up a copy of The Art of the Deal and he explains it himself:

Trump: The worst thing you can possibly do in a deal is seem desperate to make it. That makes the other guy smell blood, and then you’re dead. The best thing you can do is deal from strength, and leverage the biggest strength you can have. Leverage is having something the other guy wants. Or better yet, needs. Or best of all, simply can’t do without.

Unfortunately, that isn’t always the case, which is why leverage often requires imagination, and salesmanship. In other words, you have to convince the other guy it’s in his interest to make a deal.3

There’s no doubt that Trump has effectively distracted the world from all the difficult and unpopular things he’s about to do. What’s more, he eked out a significant list of concessions from the targets of his ire.

In response to Trump’s sabre-rattling, Ottawa unveiled a suite of border security measures and anti-fentanyl traffic initiatives. Much of it isn’t new, per se, but it is likely to be significantly expanded and sped up. Denmark is racing to improve security on Greenland, and a host of other NATO countries are already putting together packages to appease Trump.

There are a great many terrible things to say about Donald Trump. But his political superpower is that he can scare ‘normal’ politicians out of their complacency and into action. In self-fashioning himself into the erratic, dangerous, and destructive force his supporters love and critics decry, Trump managed to achieve a series of real wins.

So it’s fake, but it’s also real.

In the Art of the Deal, Trump tells the story of enticing Holiday Inn to partner with him in Atlantic City. There were other developers being considered, but Trump achieved the deal because Holiday Inn believed his casino project was nearest to completion — except it wasn’t. It was all lies and bravado.

“My leverage,” Trump wrote. “Came from confirming an impression they were already predisposed to believe.”

Upholding Conventions Nobody Believes

Thomas More was an unlikely Enlightenment figure.

He was a humanist and a proto-socialist, but he was also an ardent defender of the Catholic Church and, as Lord Chancellor of England, responsible for systemic persecution and atrocities.

Stephen Greenblatt suspects that More was patient zero for the politics of self-fashioning.

“His is a world in which everyone is profoundly committed to upholding conventions in which no one believes,” Greenblatt wrote in his 1980 book which introduced the concept. He goes on: “The conventions serve no evident human purpose, not even deceit, yet king and bishop cannot live without them. Strip off the layer of theatrical delusion and you reach nothing at all.”4

More, particularly in his seminal work Utopia, seemed to be flaying the pomp and circumstances which had kept a stranglehold on Europe for so long. (Dispatch #115)

“Why should men submit to fantasies that will not nourish or sustain them?” Greenblatt asks. “In part, More's answer is power, whose quintessential sign is the ability to impose one's fictions upon the world: the more outrageous the fiction, the more impressive the manifestation of power.”

More’s desire to wield these conventions for his own ambitions ultimately proved his undoing: In going head-to-head with King Henry VIII, More ultimately lost his.

In the centuries since, the politics of self-fashioning have been very in vogue, as Trump, master of outrageous fiction, has shown. But that’s not to say that he’s the only one self-fashioning.

Earlier this week, The Daily Show announced a surprise guest: Mark Carney, ex-governor of both the Bank of Canada and Bank of England and, as he teased in the interview, aspirant to become the next Prime Minister of Canada.

Carney is, there’s no doubt, a brilliant guy. But watching the interview — his first real media outing as he prepares to jump into politics — I was struck by how fake it all was. How absurd the conventions were.

Just on the first level, Stewart’s is a fake news show. But it’s also a place where, occasionally, real serious conversations happen. Not here, however. Carney and Stewart discuss Trump’s overtures to buy Canada — “we’re not moving in with you,” Carney grins. “It’s not you, it’s us.” Laughter. Then there’s a series of warnings about right-wing populism, wagging a finger at those who would go down that path. Poilievre, he sniffed, had a wrong-headed “‘starve the beast’-type approach.”

The interview continues on mostly that footing (torturing, along the way, the relationship metaphors) for 20 minutes. They conclude with Carney having delivered lots of one-liners but without having said much at all. It felt like watching Putin do judo. His subsequent campaign launch was even fuzzier, even more enamoured with ceremony and pablum.

Trump self-fashions himself into the bold, ambitious, hustler, move-fast-and-break-things ethos of crypto bros and the get-rich-quick aspirations of 20-somethings. Carney, meanwhile, is fashioning himself into the same tired tropes of neoliberalism: Vague assures that we can still build big things, tax the rich, but avoid the pitfalls of populism on the left and right.

Both of these efforts are deeply insincere. And they come from a very similar place: The great promise that our 21st century politics would be a two-way street of digital engagement.

The grandfather of these uber-online politics, Barack Obama, swore that the internet would unlock a kind of collaborative discourse that would reshape politics into something fairer, more effective, and more constructive. I think I speak for all of us when I say: lol.

Politics, instead, became a one-way deluge: Of tweets from politicians’ accounts run by a team of 30-somethings, fundraising texts, Instagram videos, clips made to go viral, celebrity endorsements, late night talk shows, cringe-worthy memes, and emails that begin friend…

This kind of politics is innately condescending. And it has, I think, run its course, as Trudeau’s departure shows. We can see it, too, in the wreckage of Kamala Harris’ superficial and star-studded campaign. Her approach to the race bordered on contemptuous of the public, and the public reacted in kind. (Nikki Glasner hit it perfectly at the Golden Globes last week: “You're all so famous, so talented, so powerful. I mean, you could really do anything — except tell the country who to vote for.”)

Despite this clear dead end, politicians have continued to self-fashion themselves as Obama. It has only increased the absurdity between their tired rhetoric and their inability to fix the myriad of crises facing the Western world: Horrific wars in Gaza and Ukraine, an endemic housing crisis, stagnant wages amid sky-high corporate profits, worsening services amid a technological revolution, and so on. People are, rightly, asking: Why can’t we figure this shit out?

And yet this class of liberals really resented you questioning them. The populists, they reply, will be so much worse.

That may be true. But at least the populists know how to talk to people.

Kayfabe Politics

The character Trump plays, the one he has become, is both over-analyzed and under-appreciated. He’s had his head shrunk by armchair psychologists and had his every tweet dissected by behavioral analysts.

But this all assumes he’s sincere. We know he’s not. He’s self-fashioning to become the man his supporters want him to be, in a way that Obama once promised and never achieved.

This constant conversation, a feedback loop of collaborative politics, has fostered a platform of intense cruelty. The very people who are likely to be the nuclei of his administration — from RFK Jr to Kash Patel — are there because they were able to create and harness this malign terminally-online paranoia, distrust, and hatred.

Even before he’s been inaugurated, Congress has raced to pass the Laken Riley Act, which obligates the state to detain migrants suspected of even minor crimes and unleashes the states to enforce federal immigration law in chaotic new ways. The bill was a bipartisan effort, a clear reflection of just how much Trump has cajoled even Democrats into his immigration policies.

This is just the opening salvo.

Trump’s agenda — mass deportation, eviscerating environmental laws, smashing the social state, dismantling public health, dismantling rights for women and transgender people, unleashing corporate greed — will be mean and damaging because the people who contribute to his political identity want it to be so.

Most importantly in this whole interplay: It’s fun. It’s occasionally even funny. Those who contribute to the participatory politics of MAGA find community, entertainment, even meaning. They are self-fashioning themselves into Trump’s acolytes in the same way that Trump is self-fashioning himself into the myth they’ve built together.

Nowhere is this more prevalent than in the sea of AI slop. There’s Trump brandishing a rife on the back of a giant cat as he heads off to do battle with Haitian migrants. There’s Trump leading the American revolution. There’s Trump praying. Not only has Trump’s sea of supporters enthusiastically generated his propaganda, he has fervently shared and promoted it.

Using e-consultation platforms to do policy ideation? Boo! Using Truth Social to make an AI image of the Easter Island statues wearing MAGA hats? Yay!

Do any of his supporters actually want him to take over Greenland? It doesn’t matter, because it’s triggering the libs, and that’s a victory onto itself. As an added bonus, it helps to cement the idea that America is under assault from the rest of the world, and it must punch back twice as hard.

To make this case, I’ve given you a lot of painfully esoteric and high-brow allegories. Putin, Fandorin, More, and Carney. But there is a far more apt comparison.

Since even before he launched his political career, Trump has recognized the broad cultural appeal of professional wrestling. He became chummy with the WWE’s (now-disgraced) leader Vince McMahon — his wife, Linda, served in his first administration and is now slated for a bigger job in this one.

Many have made the case that Trump’s politics amount to kayfabe: The state of suspended disbelief that hangs over the wrestling industry. At its best, kayfabe builds a world which doesn’t take itself too seriously, which can both satirize real life while also providing an escape from it. But in recent decades, the McMahon’s version of kayfabe took on a darker hue. As Abraham Josephine Riesman, Vince McMahons’s biographer, writes:

Riesman: Old kayfabe was built on the solid, flat foundation of one big lie: that wrestling was real. Neokayfabe, on the other hand, rests on a slippery, ever-wobbling jumble of truths, half-truths, and outright falsehoods, all delivered with the utmost passion and commitment. After a while, the producers and the consumers of neokayfabe tend to lose the ability to distinguish between what’s real and what isn’t. Wrestlers can become their characters; fans can become deluded obsessives who get off on arguing or total cynics who gobble it all up for the thrills, truth be damned.

Does all that remind you of anything?

The Need for Sincerity

I don’t know what four more years of Trump means. I have to suspect that it will not mean the annexation of Canada or Greenland. I believe it will mean cruelty to migrants whose only crime was trying to chase the American dream, trans people who just want basic respect, and a host of others who don’t fit into the reactionary vision Trump represents and who are easy targets for his high-velocity online propaganda machine.

And I know that the hollow patronizing from his liberal critics isn’t going to be an effective check on his power nor a popular alternative.

So what does an alternative look like? Because there’s not a ton of time to figure it out.

In the coming weeks, the Canadian Liberals will pick a new leader, the Democratic National Party will choose a new chair, and the broad swath of small-l liberals — the spectrum from the squishy centre left to the neoliberals to the mainstream centre-right — will contest elections across Europe and hope they can stave off a far-right, illiberal challenge.

There’s no doubt that optimism and ambition are key components of a better formula. But so, too, is sincerity. The kind that admits fault and owns failure. The kind that isn’t stuck in broadcast mode but which participates in conversation.

The only moment I’ve heard that kind of sincerity in recent weeks, came from Pillai, the Premier of the Yukon. He was ruminating on Ottawa’s new anti-fentanyl strategy.

While south of the 60th parallel may monopolize the conversation about the opioid crisis, Yukon has the country’s highest opioid overdose death rate.

“In seven days,” Pillai told me, “the federal government put together the most ambitious plan we’ve ever seen to deal with fentanyl.” That is, for sure, good news. But it was put together, after more than a decade of unimaginable volumes of death, “to respond to a tweet.”

There are no easy solutions to the opioid crisis. But there are a lot of hard ones that require an enormous amount of work. And, as recent weeks have illustrated, we are capable of putting those plans into action when we are adequately motivated. Pillai’s willingness to admit that, and to recognize that we haven’t done that, was oddly edifying.

“I, personally, felt really uncomfortable and guilty as a leader thinking: That’s what it took.”

For years, liberals have remained fundamentally stuck in their ways — while the left and non-reactionary right have only tried to emulate their tactics. They have lectured their critics to stop whining, insisted that things are better than they may seem, and defended their half-measures as sufficient, all the while insisting: We hear you.

Yet when Trump comes along, fundamentally in charge of the pervasive frustration present in Western society, he forces them to do more in a few days that they’ve done in years.

Now is the time to dismantle this rigid, inflexible, and paternalistic liberalism of self-fashioning, and figure out what an actual democratic, participatory politics would look like. It’s not enough for our politicians to become the symbol they think we want, it’s time they actually start speaking to people in real terms — offline, whenever possible — and leave the absurd conventions behind.

Now would be an ideal time for Carney, or one of his competitors, to model good behavior, drop the vacuousness of this modern liberalism, and show everyone what better can look like.

We don’t have five or ten years to figure this out. It needs to happen today.

Happy new year, I suppose!

I hope everyone had as slow-moving a holiday as I did.

I’m just getting back into the swing of things. I was, unsurprisingly, on Trudeau-resignation duty over at The Toronto Star, where I’ll be (hopefully) putting the gears to Trudeau’s aspirant replacements. (Expect to see some overflow of that work right here, on BE&S. Or, perhaps, on a whole new newsletter….)

I’ll have a deep dive coming on the future of Ukraine’s peace negotiations in Foreign Policy, hopefully by later today.

I’ll be back like clockwork next week, with an interesting conversation on the future of nuclear proliferation. Fun, breezy stuff.

And thanks, as always, to Erwin Dreessen for his copyediting help on this tome!

Until next time!

Russia’s Revolution: Essays 1989-2006, Leon Aron. (2007)

Post-Soviet self-fashioning and the politics of representation, Brian James Baer. in: Putin As Celebrity and Cultural Icon, edited by Helena Goscilo. (2013)

The Art of the Deal, Donald J. Trump and Tony Schwartz. (1987)

Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare, Stephen Greenblatt (1980)

I think anyone capable of looking at Trump objectively can see what he's doing. He's not serious but he is making a serious point. He is pushing Europe to step up in NATO and start pulling their weight. He has poked strategic partners like Greenland and Canada to do more in the Arctic. He is poking Canada and Mexico on border issues. He has fired shots across the bow in the Middle East. All of these silly presentations have accomplished results. Canada has been discussing borders since 2015 and voila, have only just now started to take new measures. Mexico has also started to break up migrant caravans. You may not like Trump, but he ceratinly gets results quickly.

Tell me when you run for political office ... I will vote for you!