“The press claim that you claim to be the son of god.”

Terry Wogan, legend of the BBC, is staring at a man in a pastel tracksuit, his hands tented, with total seriousness.

“Mmhmn,” he responds.

“Is that true?”

“Yes, you see, the thing is-” the audience starts laughing “it’s quite funny really. You know, 2,000 years ago, had a guy named Jesus sat here, you’d still be laughing. It’s really funny that we’ve not moved on that much. There’s been many missions, if you’d like, over the past 12,000 years to try and free the earth from a force that is trying to work against the Godhead.”

The man in the aqua-and-pink tracksuit was a familiar face to the British public. He had been goaltender, briefly, for the Hereford United football club before moving over to the BBC to present sports. Then, he moved on to the Green Party, fond of their approach to homeopathic medicine, becoming their spokesperson in short order. But soon he quit the Greens, too, to focus on a new effort: Speaking for the Godhead.

This is the story of how David Icke became a cultural and political phenomenon.

This is the story of how one man managed to marry magical realism with dour anti-semitic paranoia. How his warped philosophy infected our democracy. How a man managed to convince us to

suspend disbelief

distrust the media

and fear the lizard.

In April 1991, The Guardian ran a review of one of Icke’s earliest books.

One of the many astounding pieces of brand new information in David Ick'e book, the Truth Vibrations, is that...[Francis] Bacon was the son of Queen Elizabeth I and the Earl of Leicester. Icke can speak with authority on this subject since in a former incarnation he was himself Anthony Bacon, brother of the most famous Francis. Icke has been all sorts of other interesting people in his time, or times. Although he has been to the planet Mercury, it seems that he actually hails (as does his wife Linda) from Oerael...

It goes on like that for awhile. The daily paper casts him off as “a few bricks short of a load,” and quotes others to dismiss him as “round the bend,” “flipped,” “daft,” and that he’s “gone off his bike.”

"What it boils down to is perfectly simple,” Guardian reviewer Richard Boston wrote. “Either David Icke is the new Messiah (or John the Baptist), or he's barking, or he's a brilliant self-publicist. Or (and for what it's worth, this is my opinion) he's all three.”

The review quotes some of the peace-and-love morals at the core of Icke’s book and concludes: “I'm sure he is completely harmless."

At this point in the early 1990s, Icke’s shtick was new age mysticism with a healthy dose of delusions of grandeur. He began prothelysizing that the world would soon end. (It didn’t.)

Icke, early on, definitely seemed sensitive to the criticism. Rounds of jeers from the media led him to flee the country. He left for Canada, for a while, to escape the mockery. He had a polyarmorous relationship with his wife and another woman. He wrote more books.

It was a lot of peace and love, I’m the son of the Godhead type stuff.

But despite being one of the world’s most famous cranks, the public couldn’t help but side with him.

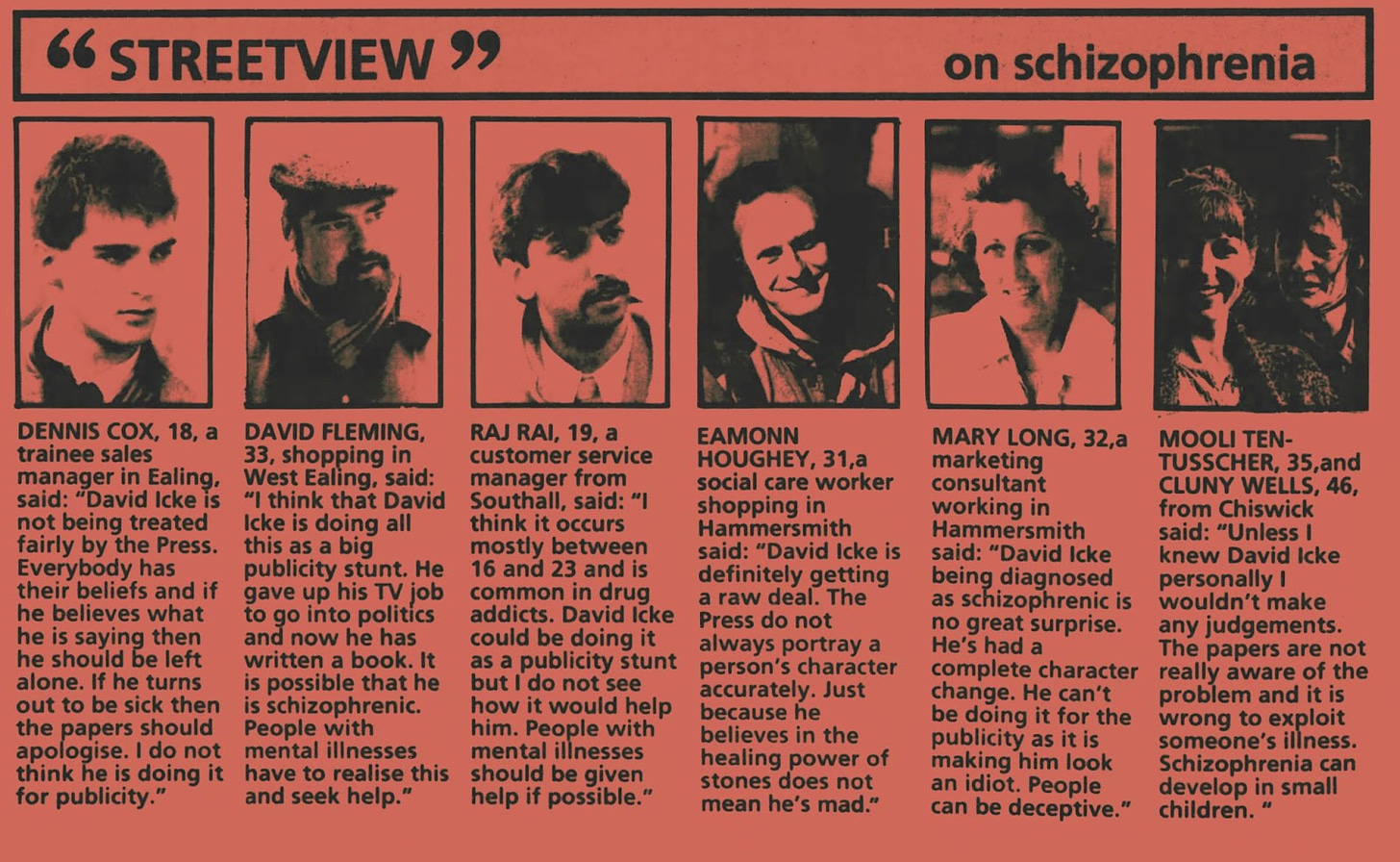

When the Ealing & Acton Gazette ran a story about Icke, asking “is this man gifted or ill?” it tried to paint him as a sufferer of undiagnosed schizophrenia. They put that question to locals on the streets of West London. Maybe he’s ill, maybe he’s not, they concluded — but the media’s treatment of him has been the real problem.

The whole ordeal undoubtedly gave Icke some tougher scales. Like a leather-skinned Iguana, he crawled back to the United Kingdom to continue building his new age empire.

David Icke became David Icke, as we vaguely know him today, in 1994. (If you have no concept of who David Icke is, well this confusing ride is about to get quite wild. I encourage you to start keeping track of each instance of ominous foreshadowing that comes up in Icke’s backstory. Let me know your tally in the comments.)

1994 was the year he published The Robot’s Rebellion. It had all the spirituality that readers came to expect from Icke — long treatises on chakras, meditations on the nature of the universe, the divide between our real selves and our physical bodies — but the peace-and-love message had been married to something more dour.

The Robot’s Rebellion was the (supposedly) true story of the epic universal battle between good and evil. Between the Godhead and its volunteers, and Lucifer and his evil energy. The horrors of human history — colonialism, slavery, war — was a manifestation of that evil. It was all enabled, he said, by the agents of Lucifer: Chiefly, the Illuminati. Their plan was “world domination” and they were capable of influencing both government and masses.

“In the 1800s, some documents surfaced called the Protocols of the Wise Men of Zion,” Icke writes.

In short, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion (as it’s normally called) is an anti-Semitic forgery that purports to be the official text of an international Jewish conspiracy that has controlled international finance for eons, and which secretly controls civilization as we know it. These documents are fake, a lazy plagiarization of a work of fiction by two Russian aristocrats designed to poison Tsar Nicholas II against his economic modernization plans.

Despite that, the Protocols have become an essential bit of kit for anyone looking to whip up anti-Semitic fervour. That includes Adolf Hitler, who cited the Protocols in Mein Kampf. And, of course, David Icke.

Rich families like the Rockefellers and Rothschilds were the chief agents of this international conspiracy — which, Icke says, is Jewish but not exclusively so — but they had permeated all walks of life. “This Brotherhood Illuminati elite began to infiltrate the universities and the media, and this is now widespread. It controls the media, for sure.”

One particularly powerful tool of this international conspiracy? The creation of the U.S. Federal Reserve — a “financial network, led by the Rothschilds, the Rockefellers and others.”

Far from disqualifying Icke from public life, these new proclamations boosted his stature, turning him into a sort of jester in the public court.

Certainly, some of Icke’s ideology was old hat by this point. Shortwave radio host William Cooper, broadcasting from a compound in Arizona, had married UFOlogy with paranoia about the Illuminati and coming New World Order to great effect: Netting tens of thousands of loyal listeners, at least, and directly inspiring Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh. His fans included Icke himself, who glowingly cites Cooper in his books.

But Icke, a former British footballer with a calm and disarming charm, would be more effective than Cooper ever could be. (Cooper would die in a shootout with police a few years later.)

While he may not have had the doomsday vibes of Cooper, Icke made no bones about it: Good was losing in its fight against evil.

As he explained in a 1994 talk:

“Today, the manipulation to bring about this New World Order pervades every area of our lives…What the New World Order means is the creation of one world government to which all nation states would be subordinate. One world central bank, one world currency, that wouldn't be physical money, it would be credit. One world army and, as I'll come to later, a microchipped population.”

He won fans. In 1997, Wyoming state representative Carolyn Paseneaux showed one of Icke’s videos to a captive audience. Icke, she promised the crowd, per the Casper Star-Tribune, “gets into the Rothschilds, the Rockefeller, the Trilateral Commission, and how our president plays into that."

This is where the lizardpeople come in. As Icke wrote in The Biggest Secret, in 1999:

In a remarkable period of 15 days as I travelled around the United States in 1998, I met more than a dozen separate people who told me of how they had seen humans transform into reptiles and go back again in front of their eyes. Two television presenters had just such an experience while interviewing a man who was in favour of the global centralisation of power known as the New World Order. After the live interview, the male presenter said to his colleague that he had experienced an amazing sight during the interview. He had seen the man’s face transform into a lizard-like creature and then return to human.

It’s easy to laugh off a man warning of a reptilian global conspiracy. But the question around Icke has always been: When he says lizardpeople, does he really mean lizardpeople?

By the middle of his book, Icke comes around to lamenting the scourge of anti-semitism. Nobody has been more “had” by this New World Order than those who “consider themselves Jewish.”

Icke begins spinning a tale about two types of Jews: The people of the book who are ignorant to the real ways of the world; and a race of space reptiles who really run the show. The Rothschild bloodline isn’t Jewish at all, he says, but reptilian. That’s why the Rothschilds “funded and supported the Nazis.” (A flagrant, ahistorical, lie.)

The space reptile fake Jews were also members of the Khazar empire that mass-converted to Judaism in the 8th century. Naturally.

“One bloodline which came from the reptile-Aryans within the Khazar empire in the Caucasus Mountains are the Rothschilds. Their leading members are reptile full bloods, reptilians knowingly occupying a human physical form,” he writes. (Oh, of course!) “No overview of the financial manipulation is possible without considerable mention of the Rothschild gang.” (It all makes sense now!)

Through that totally arbitrary line in the sand, Icke manages to cast off allegation of anti-semitism while still being outright anti-semitic. The Anti-Defamation League? It was “set up precisely to condemn as racists those exposing the [Illuminati] Brotherhood.” In another book he writes: “The Global Elite has two main defence responses — assassinating those who are lifting the veil or assassinating their character by branding them anti-Jewish and Nazi.”

Sounds familiar.

Sometimes, in covering conspiracy theorists like Alex Jones and David Icke, I feel like I’m just retracing Jon Ronson’s footsteps.

The hilarious and irreverent British writer has chronicled extremists and conspiracy theorists for decades — with enough aloofness that they are inclined to indict themselves without much prompting.

In 2001 Ronson flew to Vancouver, for The Guardian, in advance of Icke’s book tour arriving in the West Coast Canadian city.

"Do you think that, when David Icke says lizards, he means Jews?" Ronson asked an anti-racist activist preparing for Icke’s arrival. “Of course!” came the reply.

When Icke showed up, Ronson dutifully followed him around as the lizard-adverse author saw conspiracies everywhere: From the scrutiny at customs to a canceled radio interview. Everything was part of the global plot to squash his whistleblowing.

At an odd meeting of the minds between Icke’s supporters and local anti-racist organizers, there was an effort to sell the former goalkeeper to diffuse the local conflict. Icke’s surrogates argued that, lizards aside, he wasn’t arguing any position that intellectual (Jewish, they dutifully note, intellectual) Noam Chomsky hasn’t said himself. The local activists shot back, Ronson reports, "Firstly, Noam Chomsky is Jewish. Secondly, Noam Chomsky is not mad. Thirdly, Noam Chomsky is, in fact, an intellectual. And, finally, Noam Chomsky is not an anti-semite."

Despite a strict no-lizard-talk edict, Icke’s supporters let it all hang out: There are 20 lizard species! Grays! Adopted Grays! Troglodytes! Crinklies!

The exchange, I gather from Ronson’s reporting — encapsulated in Them: Adventures with Extremists — goes on for awhile. It did little to convince the anti-racist activists to accept Icke in the community. But it didn’t matter, really.

"He was a martyr,” Ronson wrote of Icke. “His fans started approaching him on the street, shaking his hand, sometimes even breaking into spontaneous rounds of applause, offering words of support." One old lady pulled Icke aside on the street to tell him: "It's so terrible what those awful Jewish people are doing to you"

Icke would go on a local Vancouver television station, over the objections of the supposedly all-powerful coalition against him. The station set him against a local psychologist, who offered an awfully clear-eyed read of Icke’s appeal.

“People like to enchant themselves,” he said. “They want there to be a grand conspiracies by superpowerful beings, rather than just a bunch of mistakes made by decent people.”

Icke shouted over him. “Is he going to go on forever!”

People found various ways to accept Icke. Some, no doubt, loved his quick wit and charm. Some loved the idea of his tackling the global elites. Others, sure, loved the lizard stuff. Maybe some were attracted to the new age religion. Without a doubt, many just loved the anti-semitism.

All told, they made a real coalition.

They laughed at Alex Jones, too, when he was just a small-time radio host in Texas. A local Austin alt weekly wrote in 1997 that their favorite conspiracist-on-air was tilting at windmills, but, hey, “he is cute.”

Icke and Jones were singing from the same hymnbook, in many instances. They both saw a secret international cabal of evildoers. They both obsessed about the Illuminati, and the Bilderberg Group, and secret societies. But Jones focused on nebulous connections between individuals and governments. Icke pinned his red twine onto the stars and universe itself, into a cosmic Satanist plot.

Jones was a conspiracy magpie. He stole plenty from Cooper. But he borrowed from Icke, too.

In 1996, Icke wrote:

There is a sexual “playground” for leading American and foreign politicians, mobsters, etc, involved in the Cult of the All Seeing Eye and the New World Order. It is called Bohemian Grove in Northern California […] This is why so many world leaders are involved in Satanic child abuse. The Cult of the All Seeing Eye is based on Satanism and the black use of esoteric knowledge and this same cult controls the appointments to the major political, economic, and administrative posts in the world. Therefore you find that a staggeringly high proportion of people in the top jobs are people connected to this cult and its sexual abuses. The best actors are in Hollywood? No, no, they are in the parliaments and political parties.

Bohemian Grove is, in fact, a sophomoric bro-down of the world’s rich and powerful. Simpson’s voice actor Harry Shearer has been there and, he says, it was a big frat party. No child sacrifice at all. Not even a bit.

By 1999, Icke was warning of an “armoured lizard called Moloch Horridus…an ancient deity to which children were sacrificed thousands of years ago and still are today in the vast Satanic ritual network.”

His books included spooky photos of the site. He relies on testimony of a “CIA mind-control slave” who alleges the Grove is a “sexual playground for leading American and foreign politicians, mobsters, bankers, businessmen, top entertainers, etc, who are initiates of the Babylonian Brotherhood.”

In 2000, Jones took a camera crew to infiltrate the site. He, mostly, fails, but that doesn’t stop him from insisting that the elites at Bohemian Grove are sacrificing children to Moloch. Just like Icke had said.

Every time it felt like Icke’s bizarre prognostications were so far beyond the realm of sanity that it would alienate every last one of his followers, it didn’t. It just made them more bold.

Perhaps, it alien-ated them.

(Hold for laughs.)

In the years since Icke’s improbable rise, he has morphed and adapted his messianic message. Always, of course, keeping a core truth at the center of his books: That a race of lizardpeople, organized through secret societies, are locked in an epic battle against the forces of good to control our world.

You could laugh off Icke, but it was tough to laugh off the ideas that he was putting forward in his books, and which were gaining real traction.

He writes that “the Brotherhood can orchestrate a concerted attack on the human body and its mental processes through the drugs, vaccines and food additives. Genetically-engineered animals and food is part of this, also.”

Elsewhere: “The same Brotherhood now control the world banking and trading system via the central banking network, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organisation, the Bank of International Settlements and so on.”

A few years on: “The Illuminati financial sting is very simple and spans the period from Sumer and Babylon to the present day. It is based on creating money that doesn't exist and lending it to people and businesses in return for interest. This creates an enormous debt for governments, business and the general population and allows you to control them.”

It all comes back to the lizards: “These are the bloodlines behind the World Wars; September 11th and the 'war on terrorism'; and all the needless suffering, conflict and depravation that we see across the world. It doesn't have to be like this. It is just that the Reptilians want it to be.”

And there’s a grab bag of other stuff. “Fluoride in the water is a mind suppressant.” The Illuminati are still on “moon time,” and killed Princess Diana in accordance with lunar numerology. “The Illuminati have organised their own agents provocateur to start the violence we see on the news broadcasts.”

Of course, not anyone skeptical of the central banks, or even those who follow a fantastical alternative explanation for 9/11 are Icke’s disciples. But some of them sure are. Other influencers in this space borrow heavily from his, frankly, impressive world-building because he’s so damn good at it.

Icke also offered an adaptable metatheory. He could plug in to just about any thinkers’ world — from Alex Jones, who still promotes Icke on Infowars; to Jon Rappoport, author of AIDS Inc, which purports to expose “the real killers behind the disease.”

Despite the outlandish claims he makes, Icke is a pretty easy figure to fall in with. He’s rather funny. (“I couldn't be the reincarnation of Jesus because I come from a place called Leicester and there's no way you'd find three wise men and a virgin there!" he told Rappoport in an interview.) He sets a clear dichotomy: There are those who have been “awakened,” and those who are the sheep. (You’re invited to pick a side.) He ties everything together neatly. If anything is incongruous or contradictory in his carefully-constructed world, he’ll build an explanation around it. Everything in its right place.

Over the years, students and fans of Icke have included The Color Purple author Alice Walker; actor and, er, comedian Russell Brand; heavy metal guitarist Matt Pike; and, well, a lot of other people.

By 2011, Icke had sold some 140,000 copies of his books. He embarked on a world tour, presenting at least at some stops, an eleven-hour lecture — selling out multiple stops, including Wembley Stadium in London. In 2013, Icke crashed the annual Bilderberg conference, with The Independent reporting that police expected 10,000 to show up.

Thomas Lane was a fan of Icke, too. Lane brought a gun to school and shot three of his classmates, killing three. It’s hard to say what impact Icke’s conspiracies had on Lane, but it’s easier to understand the influence he had on Kyle Odom, who shot his pastor six times in 2016 under the delusion that he was one of the lizardpeople. (The pastor, remarkably, survived. Odom was arrested while throwing documents over the White House fence.) In 2019, David Anderson opened fire in a Kosher supermarket in New Jersey, killing three, operating under the belief that it was run by a class of Khazar-Nazis. Anthony Quinn Warner, who blew up his camper in downtown Nashville on New Year’s Eve 2019, was a student of Icke as well.

No matter. For Icke, all mass shootings are part of the Illuminati plan. False flags.

But Icke, to his credit, hasn’t lent himself to the jingoistic nationalism that has emerged in recent years. He doesn’t worship Donald Trump. He isn’t fond of guns. He’s anti-war.

Icke’s toxic influence is in his ability to condition people to unplug and accept the insane. If I were conspiracy-oriented, I might accuse Icke of being the real mastermind behind COVID-19 — because the pandemic was probably the single greatest thing to happen to Icke.

Icke was one of the earliest proponents of the idea that there was a link between COVID-19 and 5G networks. That the pandemic was all orchestrated. That vaccines (and this is long before there were vaccines) would be used to control us. Really, Icke said, this faux-virus has validated everything I’ve been saying this whole time.

Despite social media bans, hundreds of thousands of loyal followers have continued to worship the soothsayer. One of his recent videos accusing the Rothschilds of creating the coronavirus was viewed six million times.

When the University of Bristol and King’s College London interviewed nearly 5,000 U.K. residents about who they trust in respect to the pandemic, in late 2020, Icke (thankfully) came dead last. But, still, nine percent of respondents said they trusted him to some degree. For non-white folks, that number jumps to 20 percent.

A briefing note from the UK’s Commission for Countering Extremism puts it bluntly: “The scale and reach of his antisemitic conspiracy theories remains extremely concerning.”

I hope you kept your ominous foreshadowing tally going.

Trying to pinpoint every element of Icke’s influence on our current deranged discourse would be madness-inducing.

You’ve probably picked up on a fair bit of it all on your own.

Broadcaster Stew Peters’ documentary Watch the Water — which alleges that COVID-19 is, in fact, snake venom — has been viewed, on video platform Rumble alone, upwards of five million times. Hard to ignore the Icke influence there. The Icke influence is pretty obvious.

Both Q and his Anons make frequent allusions to the Rothschilds and the Khazars. The idea of satanic child sacrifice was core to the Pizzagate theory that gave birth to QAnon itself.

Icke’s effort to find secret agents of the New World Order everywhere and anywhere has been updated and remixed to make a boogeyman of the World Economic Forum, which (if you trust the denizens of certain fringes of the internet) is responsible for COVID-19, monkeypox, and an imminent plan to microchip the population and make us eat bugs. All things Icke has talked about ad nauseam.

The fact is, Icke has moved in a straight line his whole career. Society has swerved to meet him.

I regret to end this missive with an admission that I don’t know how to diffuse Icke’s pervasive ability to convince, nor do I know how to prevent the next Icke from coming along.

What I do know, however, is that you’ve got to start by understanding it.

I hope you’ve enjoyed dispatch #4 from Bug-eyed and Shameless.

If you’ve not signed up as a paying subscriber yet, you’ve still got a few editions left before the paywall slowly goes up. If you’ve got thoughts, or want to report how many notches you made on your ominous foreshadowing tally, comment below — I’m going to endeavour to respond to every single comment.

If you want to keep exploring the world of David Icke, might I recommend:

Jon Ronson’s Them; and his documentary Secret Rulers of the World

My piece for Foreign Policy on how Icke, and others, fed into QAnon’s theory of everything

Episode 3 of The Flamethrowers, where we dig deep into Alex Jones’ madness

Until next week.

I was at the lizard meeting last week and we hissed in riotous laughter over this. Also, congrats on the portmanteau of "proselytizing" and "prophesying," whatever you meant to type.