Briefly, An Intelligence Briefing

Did the "freedom convoy" have guns? Plus: Ukraine's drone problem. And: We check in with Danielle Smith

When thousands of anti-vaccine demonstrators occupied downtown Ottawa earlier this year, a question hung in the air — as thick as the diesel fumes.

Were they a threat to national security?

For those watching from the outside, the threat seemed fairly obvious. The occupiers and their trucks had paralyzed the nation’s capital. They had vowed to keep up the occupation until their demands were met, and various elements were discussing — with various degrees of seriousness — the need to remove the government. At a solidarity blockade in Coutts, Alberta, police arrested four men, seizing their cache of weapons, and charging them for plotting to murder RCMP officers.

I was chewing on that question as I paced the streets, weaving in-between the idling trucks. I was communicating with several police officers, emergency response personnel, and public safety officials about why, exactly, the enforcement of this possible national security threat was being treated with such a light touch. Detractors were making much hay of images showing Ottawa cops looking downright chummy with the occupiers. All together, it gave the impression that, at best, Canadian politeness meant anyone could occupy our capital and, at worst, police were particularly cool with the far-right.

But the one thing I kept hearing from those officers was: What if they have weapons?

It’s a question that can explain an awful lot about how the police approached the occupation, and why it took so long to clear the encampment.

It’s also a question I tried, in a pretty limited way, to answer after the occupation was cleared. I reported the following for the Toronto Star:

Fears that there were weapons inside some of the trucks proved prescient: A police source said loaded shotguns were found. (While truckers can legally transport registered firearms in their vehicles, guns must be securely stowed and are not permitted to be loaded.)

On March 24, [Chief] Bell confirmed police received “information and intelligence” pertaining to firearms in the occupation, but would not confirm whether firearms had been seized and said investigations are ongoing.

That little piece of information, tucked in near the bottom of a lengthy story, came via one emergency response source — a piece of information that was tacitly confirmed by a second source with a different police agency. I was careful in how I reported such a piece of information: A trucker having a legal firearm in their cabin, if safely stowed, is perfectly legal. While having it loaded, much less at an illegal occupation, would likely result in firearms charges, it does not necessarily mean that the owners of those firearms intended to do anything nefarious with them. But it does add a significant level of complexity for an officer trying to arrest that trucker, who may be barricaded in their cabin.

Those sympathetic to the so-called freedom convoy, particularly those who participated in it, have been roiled by such reporting. They insist they posed no national security threat, they were universally peaceful and law-abiding, and they had no weapons.

The suggestion to the contrary has been held up as a government-directed smear job.

After Chief Steve Bell made those comments — indicating that no charges had been laid and not, as MP Dane Lloyd suggests, that no firearms had been found — I checked back in with my original source, who remained confident in the information. I further checked in with the Ottawa Police Service, who stayed relatively mum about those ongoing investigations, but told me that while they might not agree with my particular phrasing, the thrust of my reporting was accurate.

Yet some folks have decided that I am an enemy of the revolution:

So I’ve largely kept my mouth shut about this topic. (I am, after all, a ghost.) I knew the ongoing commission into the convoy, and the police response, would eventually put the truth out on the line.

While there’s still plenty of commission left to go, we now have some documents and testimony from many of the top cops that shed some light on what police knew about the national security threat posed by the occupation, and confirms that firearms were seized from the occupiers.

So this week on Bug-eyed and Shameless, I respond to those calling me fake news. Along the way, we’re going to learn a little bit more about just how volatile this occupation really was.

For paying subscribers: I preview Ukraine’s top secret effort to disrupt Russia’s kamikaze drones. And: What’s Danielle Smith up to?

If you have followed the Public Order Emergency Commission at all, you may have seen some particularly bombastic reporting about some recent testimony from Ontario Provincial Police Superintendent Pat Morris. He remarked that “everybody was asking about extremism. We weren’t seeing much evidence of it,” and that the OPP “found no credible intelligence of threats.”

The pro-convoy types jumped on that testimony as definitive proof that there was an orchestrated plot to smear the occupation. The convoy organizers’ lawyers called on the Commission to call CBC President Catherine Tait to testify, declaring that “the Commission is mandated to investigate misinformation that led to the declaration of emergency. The biggest source of misinformation was the corporate press.” Others accused me of being a mouthpiece for the federal government.

Yet, as the National Post’s Christopher Nardi pointed out on Friday: The OPP’s own intelligence directly contradicts Supt. Morris’ testimony. (Some idiot misspelled Nardi’s name in earlier version of this post. It has been corrected.)

So let’s take a look at what police were actually learning about the possible threat posed by these occupiers.

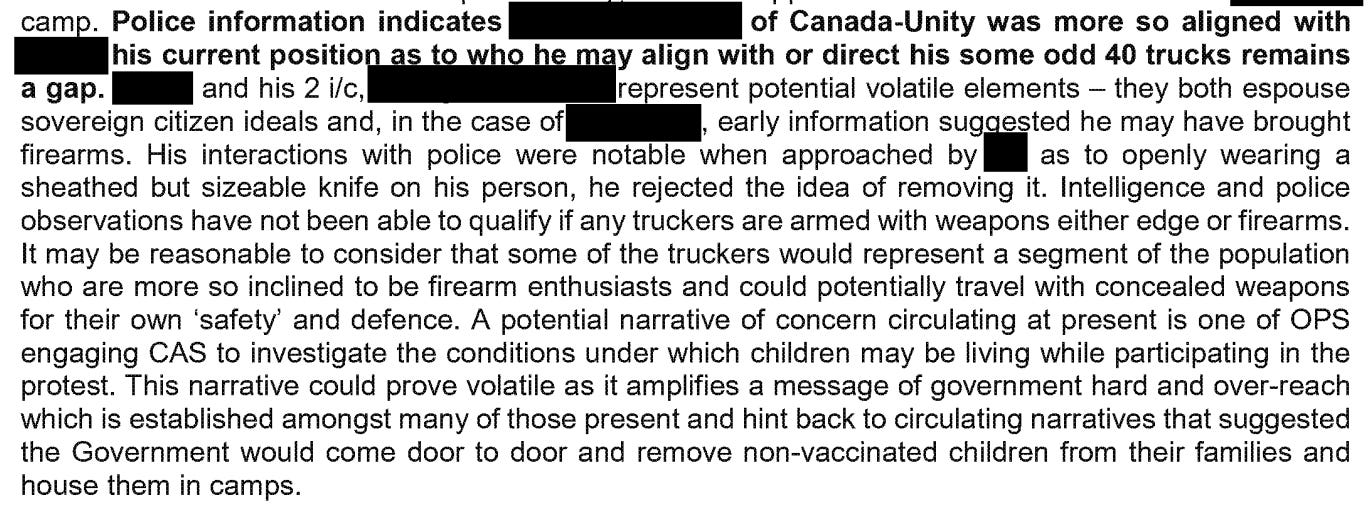

On January 13, the OPP’s Provincial Operational Intelligence Bureau — which Supt. Morris leads — wrote of the heavy involvement of the “patriot movement” in anti-vaccine activism, particularly around the upcoming convoy. Elements in that movement, they write, “continue to discuss anti-government guerilla warfare tactics where weapon acquisition, training, and ‘prepping’ for an escalation of resistance actions are taking place in some settings.”

OPP briefings, rightly, underscored that there was no evidence of any particular threat with respect to the convoy. But by the time the convoy arrived, they confessed a lack of visibility.

On January 25, just days before the convoy arrived, the OPP identified several intelligence “gaps,” including "the extent of extremist participation in convoy protest and intent of extremist actors; potential for some participants to bring weapons or be armed."

This matches with what the Canadian Security Intelligence Service was reporting to local police, through its ITAC service.

While the Ottawa Police Service was decidedly more serene in its initial assessments — there’s a whole other newsletter to be written about that — the local cops picked up on the mounting threat not long after the trucks’ arrival.

Consider this January 28 briefing note from the Ottawa Police Service:

This evening, Sgt. St Amour attended the intersection of Kent and Queen to assist an officer. As she arrived, no one was at the intersection. Several convoy vehicles parked close to the officer, blocking her in. Approximately 20 truckers approached her as she called for back-up. 25 officers responded to assist. Truckers were intimidating & taunting officers. A Convoy Marshall attended and ordered his group to leave. They eventually complied. The Marshall advised officers that even he is losing control of his members as they become increasingly aggressive.

This sort of situation happened more than once. A few days later, as the police chief met with city councillors, he remarked that their posture had “avoided full scale riots.” Yet in trying to enforce the law, “officers [are] getting swarmed” the chief said, according to meeting notes.

An operational report in early February noted:

City employees in particular have been subject to intimidation and rock-throwing when left alone in their vehicles. Officer safety has also been an issue as there have been instances where crowds have moved to intimidate officers who have become isolated or are working in pairs. During early flashpoints, crowds have even challenged large group of officers. In both instances, had an arrest been necessary it would have been next to impossible given the risk to officer safety.

On February 11, Morris himself sent a briefing for the Ottawa Police Service. In it, Morris himself notes that there are at least two groups with “elements of extremism” embedded in the occupation.

This, I think, was a pretty fair summary of the state of play. Morris was quite right to call out some of the overheated rhetoric that surrounded the convoy and occupation — there was a presence of organized and cohesive extremist movements and organizations, but it was small. We know that elements of the Diagolon movement, which is directly tied to those arrested in Coutts, were in Ottawa: Indeed, I saw one of them on the streets, taunting officers as they cleared out the occupation. We also heard that a right-wing biker gang held one particular intersection.

But, as I reported at the time, those small numbers of individuals tied to extremist movements were only one part of the problem. The other dynamic was the increasingly aggressive and bellicose majority. One group of far-right activists on the Quebec side, for example, promised they would only "leave when they get their freedom or when they are dead,” per OPS meeting notes.

Even though there were acute fears about these groups, arrests did not come until later in February. What I heard time and time again from officers and public safety officials was: We are outnumbered and facing an increasingly confrontational adversary. We do not have the authority or the capacity to enforce the law. The best we can do is mount a friendly face, avoid conflict, and try to de-escalate wherever possible.

It’s a sentiment that’s found in these documents. February 13, the chief noted it was "difficult & unsafe to arrest someone in the red zone,” but wanted to know “what are we doing to identify them and arrest them after." In response to that, one officer noted that one of the occupiers had bear spray and a “tazer in the truck.”

As this was going on, there was ample debate within the Ottawa Police Service about a course of action. Morris and the OPP seemed to prefer negotiating a resolution, and tamped down fears of extremism. Ottawa Police Service Deputy Chief Patricia Ferguson seemed to agree. She observed in her notes: “Any action taken...[with] overwhelming force will fail. It will cause escalation of actions and someone will get hurt." She was, luckily, wrong — but the sentiment was extremely sensible.

Despite these fears, as the chief put it, things were not nearly as bad as they could have been. "No deaths, no riots, no injuries,” he said in early February. But, he added, that “doesn't alleviate the risk."

Of course the risk wasn’t just that there could be weapons in the vehicles, but there was a pressing fear of “vehicles as weapons,” as OPS meeting notes phrase it.

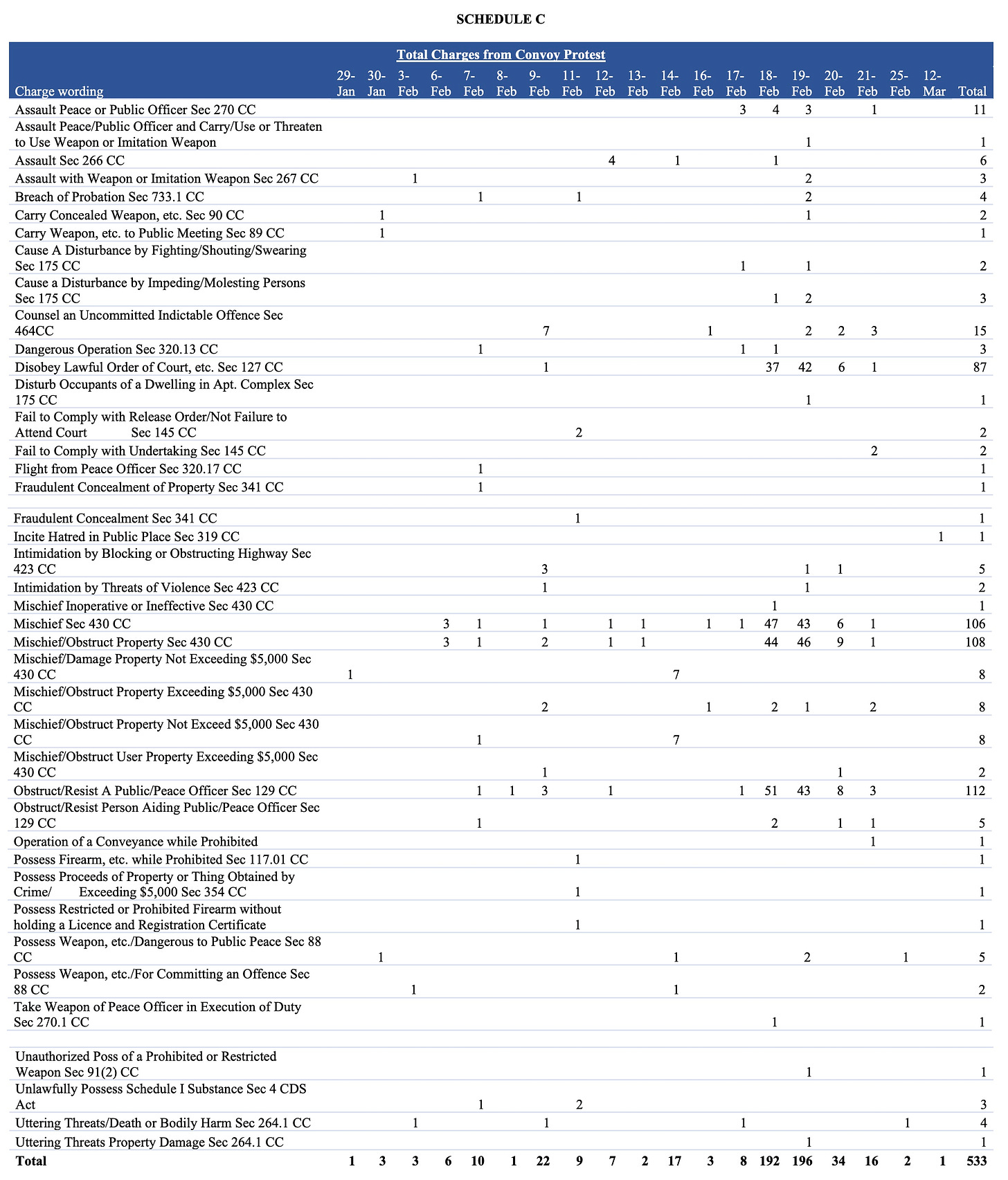

In the days before the big operation to clear downtown, police did lay firearms charges — for possessing a prohibited firearms without a license, and for possessing a firearm while prohibited. (It’s unclear if those charges were laid against the same person.) There were, in total, some 15 weapons charges laid.

While a significant amount of the most sensitive material — including evidence that may still be before the courts — is redacted in these documents, there is clear confirmation that police had intelligence around firearms being present in the occupation and laid charges relating to, allegedly, illegally-possessed firearms.

I’m not going through all of this to say “I told you so.” (Ok, I am, a bit.) My fear is that the circus around this commission risks losing the forest for the trees. As it descends into who-said-what-when, who-asked-for-which-powers, and who-hated-who, people may be forgiven for missing some of the details that elucidate just how messy and complicated this whole thing was: Not least of which, the anxiety over the presence of firearms.

For the pro-convoy crowd, they are mounting the case that the commission is exonerating them entirely — that the police are confessing the occupation posed no threat, and that there were no extremists present. That is demonstrably untrue.

At the same time: Some of the criticism of my original reporting may be partially borne out. While my source indicated that guns were discovered during the clearance operation on February 19, it’s possible that information was actually referring to weapons seizures that occurred some days earlier. If that’s the case, I’ll correct the record.

I’m heading off on vacation for the next two weeks — southern Italy! — but there should be a Bug-eyed and Shameless in your inbox next Friday just the same.

This week, my mini-doc on Ukraine’s ‘Army of Drones’ ran on CBC’s The National. Give it a watch:

Below the paywall: A few words about Kyiv’s top secret program to defend against Russia’s suicide drones.

And: What’s new with Danielle Smith?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Bug-eyed and Shameless to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.