Bombs Over Przewodów

Russia, cowed by its failures, unleashes terror from the skies. Was it a massive miscalculation?

Shortly after 1pm local time, the air raid sirens across Ukraine went off.

For the next nine hours, most of the country would be in a state of bombardment. Roughly 100 cruise missiles and suicide drones rained down across the country, slamming into power generating substations and transmission lines, knocking whole cities into darkness.

In the barrage of missiles, an explosion rocked a sleepy farming town in eastern Poland, marking the second — but most serious — instance of the war in Ukraine spilling over into the EU’s borders.

The wave of attacks come amid humiliating failures for Putin in territory that, at least according to the Kremlin, is Russian. The violence is a direct appeal to the jingoist propagandists whose unquestioning support has flagged amid defeat after defeat.

On a special Bug-eyed and Shameless, we’re going to look at the state of war in Ukraine, after one of the most reckless and dangerous days of Russian aggression yet.

Russia has a missile problem. The problem? They’re running out of them.

It’s been no great secret that Russia’s military was in dire straits even before the war in Ukraine — or, at least, that’s become clear since its invasion of Ukraine.

We probably remember well Russia’s blitzkrieg into Ukraine last February: The screaming fighter jets overhead, the array of missiles, attack helicopters descending on border towns. After months of buildup, Tsar Vladimir Putin seemed intent on showing the world what the Russian military was capable of.

That show of force was designed to finish off Ukraine quickly. The plan — which looked foolish at the time, and is now downright absurd — was to sweep into Kyiv, remove the government, and reinstall the Russian client state in Ukraine.

That plan wasn’t just arrogantly optimistic. It was necessary. Russia never had the capacity to mount a full-scale, prolonged war against its neighbour, and the specifics of that are becoming increasingly clear. Its primary advantage was in the air: Via jets, helicopters, and missiles. Without that advantage, overcoming Ukrainian resistance would be near impossible.

According to Ukrainian estimates, Russia has now used or lost 1525 drones, 278 aircraft, 261 helicopters, and 474 cruise missiles.

Let’s focus on those missiles, because those big numbers don’t tell the whole story.

Going into this war, Russia had some shiny new cruise missiles. They had the Kh-101 Kodiak.,(because it’s a bear, get it?) an upgraded version of the Soviet-era Kh-55. There’s also the slightly older 3M-54 Kalibr. It’s those missiles that have been Moscow’s preferred long-distance weapon, even if each one costs north of $1 million USD.

In July, however, Ukraine-watchers noticed something: Russia was firing other missiles westward: Namely, Kh-32 (an upgrade of the Soviet Kh-22). That’s novel because those missiles are anti-ship weapons. The UK Ministry of Defense even identified the Kh-32 as the likely culprit behind a deadly strike on a Ukrainian supermarket — a strike that Russia initially denied, insisting it had actually struck a nearby machinery plant, contradicted by evidence showing the shopping mall was hit directly. Even still, Russia kept blathering on about its “high-precision strike.”

In September, Russia even began using surface-to-air missiles in reverse — firing older S-300 missiles, which are designed to be used as air defense systems, against land targets.

The Kh-32 and S-300 are less accurate than the Kh-101, given they weren’t designed to be fired at ground targets. So why was Russia using them?

Shortages seemed to be the most likely answer. It’s not that Russia was completely out of Kh-101s, posited two researchers with the International Institute for Strategic Studies, but that “Moscow could have a floor below which it does not want Kh-101 numbers to fall in case of any contingency operation besides the ongoing war in Ukraine.” They went on to suggest that Russia may even convert some of its older Kh-55 missiles, which primarily carry nuclear warheads, into conventional missiles.

The reduction in Russia’s more capable LACM [land-attack cruise missiles] inventory and the use of Kh-22 and Kh-32 is indicative more broadly of a shortfall in Moscow’s holdings of precision air-launched munitions. The conventional guided-weapons sector suffered from woeful under-investment in the 1990s and early 2000s, with numerous projects delayed or cancelled. The Kh-101 programme, for example, started in the late 1980s but took over 20 years to enter service. Production rates, while not known, would appear to have been inadequate.

-Douglas Barrie, Joseph Dempsey (IISS)

As the summer turned into fall, Russia’s failures on the battlefield became more and more painful. Ukrainian forces had liberated the suburbs of Kyiv by March, pushing Russian forces further east. By May, Kharkiv had been liberated. Through the summer, into September, surprise attacks pushed Russian forces from huge swaths of land in the north and the south. The tide was absolutely going in the wrong direction for Moscow, and they seemed completely unable to recalibrate. A ‘partial’ mobilization seemed to revert to a classic Russian tactic: More bodies.

Even when Russia deployed new technology, it had an air of desperation. Heading into October, Russia began deploying Iranian-made kamikaze drones — essentially outsourcing the work of its domestic cruise missiles to a limited supply of Iranian-made technology. Strikes of all kinds continued, but the pace slowed.

On October 24, the Institute for the Study of War provided this interesting bit of insight, relying on Ukrainian intelligence. (Emphasis mine.)

The slower tempo of Russian air, missile, and drone strikes possibly reflects decreasing missile and drone stockpiles and the strikes’ limited effectiveness of accomplishing Russian strategic military goals. Ukraine’s Military Intelligence Directorate (GUR) Chief, Major General Kyrylo Budanov, stated on October 24 that the impact of Russian terrorist strikes against critical Ukrainian infrastructure is waning as Russian forces further deplete their limited arsenal of cruise missiles. Budanov stated that Russian forces have stopped targeting Ukraine’s military infrastructure, instead aiming for civilian infrastructure to incite panic and fear in Ukrainians. Budanov noted, however, that Russian forces will fail as Ukrainians are better adapted to strategic bombing than at the beginning of the war. Budanov claimed that Russian forces have used most of their cruise missile arsenal and only have 13 percent of their pre-war Iskander, 43 percent of Kaliber, and 45 percent of Kh-101 and Kh-555 pre-war stockpiles left.

There has also been ample evidence that even those new Kh-101 missiles were not as great as Russia had hoped. A lack of development funding, it seems, produced an inferior product. A Kh-101 fired at the headquarters of the Ukrainian Security Service in October missed its target by 800 metres, according to Kyiv. Some high-precision, eh?

According to Ukraine’s mid-October assessment, Russia had roughly 600 “high-precision” missiles left. On October 31, it fired another 50 towards Ukraine, largely targeting energy infrastructure — 44 were intercepted.

So this is where we were at prior to November: A dwindling stockpile of critically important missiles, which aren’t great to begin with; an increasing reliance on old and unconventional munitions; and a growing effort to knock Ukraine into the dark ages. All amidst a backdrop of a disastrous “partial” mobilization effort; an increasing reliance on a quasi-private military contractor pressing prison inmates into service; a retreat from territory that Putin had just weeks later declared part of Russia; and mounting criticism of the war effort from even diehard believers.

Earlier this month, I wrote in WIRED how Russia’s TV propagandists had increasingly invoked the threat of nuclear armageddon in trying to solidify public support for a war gone off the rails. It bordered on messianic. But as the ISW’s Kateryna Stepanenko explained, the nuclear sabre-rattling is likely little more than bluster. What we should really be paying attention to is the mounting calls from the influential military bloggers — ‘milbloggers,’ who I wrote about in BE&S Dispatch #19 — to scale up attacks on energy infrastructure. It’s a narrative that has increasingly been reflected on state TV.

As Moscow’s puppets tried to mount a brave face, things kept getting worse. Ukrainian forces re-entered Kherson on November 11. In the days that followed, more Russian retreats came into focus. Then, yesterday, most of the G20 leaders prepared a statement trashing Russia’s brutal war of aggression, just as the U.N. General Assembly prepared to vote on a resolution calling on Moscow to pay reparations to Kyiv.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, in Bali for the G20 summit — standing in for a most unwelcome Vladimir Putin — unexpectedly high-tailed it out of Indonesia.

Then the attacks began.

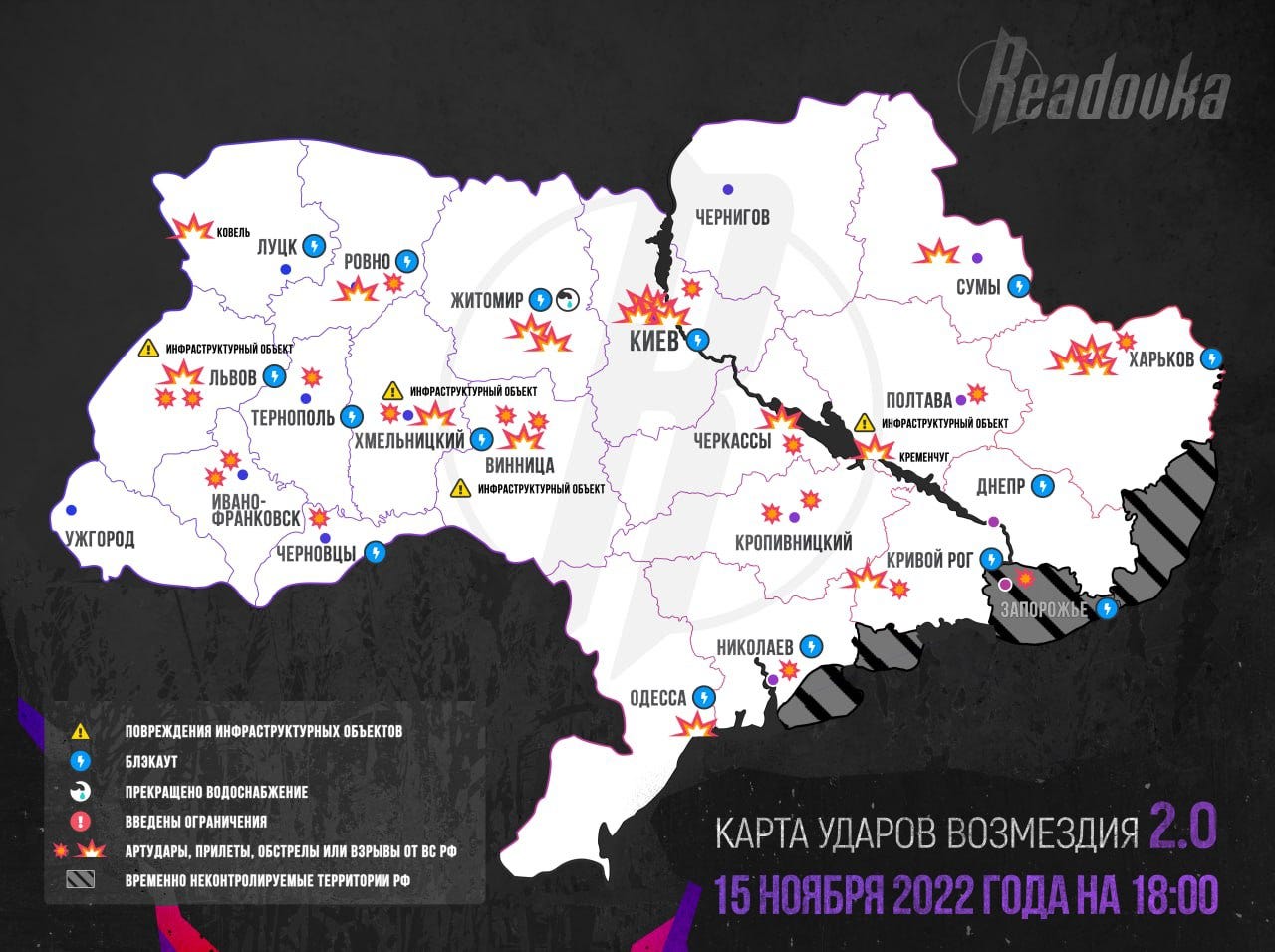

Wave after wave of cruise missiles and Iranian drones flew across the country. Kyiv, Kharkiv, Zaporizhzhia, Mykolaiv, Odessa, Cherkasy, Lviv, Vinnytsia, Rivne, Khmelnytskyi, Dnipro, Ternopil, Kropyvnytskyi, Poltava, Zhytomyr, Sumy: Nearly every region of the country was hit by around 100 projectiles. Air raid sirens sounded, civilians ran for bunkers and subway stations.

“These are not geraniums,” one pro-Russian Telegram account boasted. “But Kalibr and Kh-101.” The channels said the missiles were fired from Russian fighter jets in the east, and from ships in the Black Sea.

A Ukrainian assessment reported a total of 96 missiles and drones: 75 Kh-101 or Kh-55s; 10 Iranian-made Shahed-136 suicide drones; and two Kh-59 guided missiles, in addition to some reconnaissance UAVs.

The missiles flew towards energy substations and transmission lines, but the majority failed to reach their targets. The Ukrainian anti-air systems intercepted a huge number of the missiles — but that wasn’t entirely good news.

It was likely debris from a missile intercept that slammed into an apartment building in central Kyiv, setting the building on fire. Several other residential buildings were hit across the country — although it remains unclear if they were all hit by debris from intercepts, whether Russian missiles missed, or whether attacks on civilians were deliberate. At least one Ukrainian died in the strikes.

Ukraine’s anti-air system largely uses the S-300. Unlike Russia, Ukraine uses the system for its actual intended purpose, as an intercept missile. (That means it’s possible that Ukrainian S-300 missiles have, at some point, intercepted Russian S-300s.)

These strikes had the desired effect, at least temporarily.

With temperatures set to sink below freezing, electricity was knocked out across the country — even as far west as Lviv, which has seen comparatively fewer attacks since the start of the war. Hot water and power was knocked out completely or partially in nine cities, while others instituted rolling blackouts to manage the energy disruptions, including Kyiv.

It was a brutal day. It was the largest number of missiles fired into Ukraine in a single day since the start of the war, according to Ukrainian media.

But take into account Moscow’s increasingly-bare cupboards, and it begins to look less like an act of strength than an act of desperation. An attempt to freeze a people they can’t conquer. (A perversion of Russia’s defensive strategy against Napoleon in 1812, repeated in the Second World War.)

When countries get desperate in war, they take risks. Attacking energy infrastructure straight across the country, not just Ukraine’s east, significantly mounted the risk that those missiles would impact Kyiv’s European allies.

On Tuesday, Russia’s bombing campaign temporarily threw much Moldova into darkness. “They hit the civil and energy infrastructure of the neighboring country, endangering the lives and safety of tens of thousands of people,” Moldovan President Maia Sandu wrote on Facebook.

The strikes also disrupted the power supply to a Russian oil pipeline to Hungary, a critical energy supply for eastern Europe.

This targeting of energy infrastructure in the west and southwest has also repeatedly required infringing on Romania and Moldova’s airspace. When Russia took aim at a hydroelectric plant in late October, a prelude to Tuesday’s attack, Ukrainian missiles intercepted the projectile, rocketing debris into Moldova. (Romania is a member of the EU and NATO; Moldova is a candidate for EU membership and a NATO ally.)

So Russia knew full well how risky this endeavour was, and proceeded just the same, including launching attacks dangerously close to Poland.

While Ukrainian authorities say they intercepted some of the missiles in the West, Russian sources say the strikes destroyed a substation in Lutsk (80km from the Polish border) as well as energy infrastructure and a railway junction in Kovel (60km).

All day, Russia was playing with fire. It was lobbing missiles from at least 500km away, right along the Polish border. Its missiles had already landed in a neighbouring country after being intercepted. This was a recipe for disaster.

Around half-past 3pm, local time, Polish farmers in the border town of Przewodów reported seeing missiles (plural, worth noting) flying overhead. Eyewitness accounts, relayed to Polish broadcaster TVP, clearly specify there were two falling rockets, and two explosions.

Przewodów is roughly 100km from both Kovel and Lutsk.

Photos from the scene show a tractor severely damaged, knocked over beside a significant crater. Two locals were killed in the explosion. (“They were really good people,” a local pastor told TVP.)

At the scene, small pieces of debris were recovered — including a partially-intact piece, seemingly from the tail of the missile.

There was, of course, ample anxiety in the aftermath of the explosion. Speculation that this would necessitate the invocation of NATO’s Article 5, drawing the alliance into a direct war with Russia, was as expected as it was hysterical.

Russia quickly emerged to insist that it had nothing to do with the strike. “Polish mass media and officials commit deliberate provocation to escalate situation with their statement on the alleged impact of ‘Russian’ rockets,” the Russian Ministry of Defense said in a statement. Moscow “has launched no strikes at the area between the Ukrainian-Polish border,” they wrote, adding “the wreckage…have no relation to Russian firepower.” (That’s Russia’s bad translation, but it essentially echoes the Russian-language statement.)

A pro-Kremlin Telegram channel wrote that the missile could not have possibly been Russian: “The closest target was an infrastructure facility in the Ukrainian town of Kovel, which is 100 kilometres away from the incident. Russian high-precision missiles cannot possibly have that much of a deviation.”

There’s a problem with that argument, as a Polish statement made quite clear: No matter where the missile was fired from, it was a Russian missile. Whether it was a Russian Kh-101 or Kh-55, as Kyiv has suggested; or whether it was a Ukrainian S-300, the result of an interception — all three were made in Russia or the Soviet Union.

So the idea that a Russian missile, particularly the type of which Russia has used to strike Ukrainian targets, has “no relation to Russian firepower”; or that strikes less than 100km from Polish do not constitute attacks along the border: These are just lies.

The Kremlin lying, however, is just proof that it’s a day ending in Y. It attempted similar excuses in trying to accuse Ukraine of downing MH-17 — an atrocity we now know was committed by forces loyal to Russia.

As night fell in Poland, and officials met to analyze the available intelligence, the conclusion seemed to fall on the idea that the damage was caused by a Ukrainian missile. In Bali, Biden said it was “unlikely” that the missile was fired from Russia. Independent OSINT analysis of the wreckage came to a conclusion that the missile was an S-300.

To some extent, the origin of the rocket is immaterial: Those two deaths would never have occurred, had Russia not been firing rockets along Poland’s border — indeed, if it weren’t firing rockets or invading Ukraine at all.

But the case isn’t quite closed yet. Those eyewitness reports clearly reported two missiles flying over Przewodów and two explosions. Eyewitness accounts, particularly in these circumstances, can’t always be trusted — eyewitnesses to mass shootings, for example, frequently report seeing multiple gunmen when there was only ever just one.

The S-300 tends to fire multiple rockets at a target; whilst Russian milbloggers were bragging throughout the day Tuesday that “two rockets were fired at each object. (the first is the crown, the second is the funeral).”

So was this one or two errant Ukrainian rockets? A Ukrainian anti-air rocket chasing a Russian cruise missile? Or a Russian rocket, or rockets, just wildly off-course?

The case is far from closed.

By Wednesday, Ukrainian Volodymr Zelensky said he had intelligence from his air force contradicting the idea it was a Ukrainian S-300. “I have no doubt that it was not our rocket.” Poland and NATO, while saying indications point to the S-300 theory, absolved Ukraine of blame and said they could not rule out the idea that Russia was targeting western Ukraine in hopes of provoking exactly this kind of scenario.

Russia’s aggression may have finally tipped the scales for a controversial plan to send Polish MiG-29 jets to Ukraine. Warsaw had wanted to donate the jets to Kyiv in the spring, but Washington kiboshed the plan. Ukrainian advisor Anton Gerashchenko suggested that deal should be back on the table after Tuesday: “The best way to shoot cruise missiles down is with aviation,” he wrote on Telegram.

What’s more, Russsia’s desperate attempt to destroy Ukraine’s energy grid hasn’t worked. There is significant damage, for sure, and figuring out how to manage generation and load-balancing in a weakened grid is going to be tough. However, most of the cities knocked offline yesterday are already back up and running. The Kyiv and Kharkiv metros are back in operation. Some parts of the country are already fully back online. Work is ongoing elsewhere. While the coming days will be, as just about every Ukrainian news outlet is phrasing it, “difficult,” yesterday’s barrage simply did not have the massive effect it was likely intended to. Even pro-Kremlin Telegram channels seemed muted in their joy over the missile strikes.

So Russia is emptying its stockpiles and assuming greater risk to appease its domestic cheerleaders, and it’s not even working. It may even be backfiring.

The big question is what comes next.

For more on Ukraine’s effort to gain an advantage in the skies, you can watch my dispatch for The National about Kyiv’s Army of Drones. Recently, Ukraine has even launched a crowdfunding effort for its top-secret “Shahed Hunter.”

This weekend, I’ll be at the Halifax International Security Forum, where the situation in Ukraine is sure to be on the top of everyone’s minds. Expect dispatches from the conversation there.