Beggar Thy Neighbor, Beggar Thyself

Quack economics give us a trade war

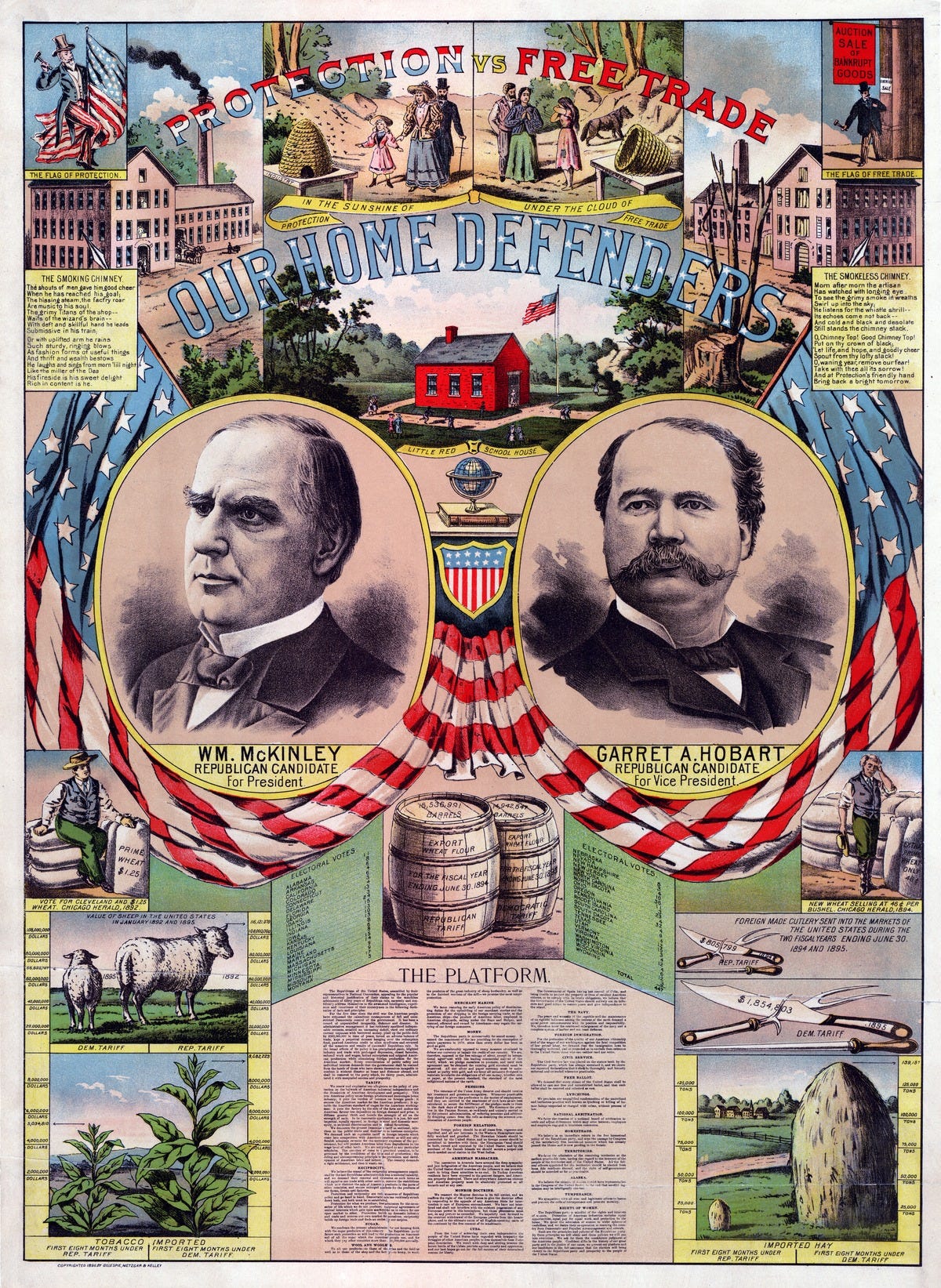

The 1896 election came down to a choice.

Americans could choose to live “in the sunshine of protection,” with Republican candidate William McKinley, or “under the cloud of free trade” with the Democrats. A campaign poster asked voters to choose: Would you rather raise sheep, grow tobacco, farm hay, and make cutlery here, at home? Or import it from abroad?

A poem summed up the risk at hand:

O, Chimney Top! Good Chimney Top! Put on thy crown of black, Let life, and hope, and goodly cheer Sprout from thy lofty stack! O, waning year, remove our fear! Take with thee all its sorrow! And at Protection's friendly hand Bring back a bright tomorrow

In order to get the good chimney top billowing black smoke once more, McKinley said America needed just one thing: Tariffs.

McKinley had, as a congressman, written a bill that helped cement America’s love for import duties, and he had made most of his political career pitching protectionism for American industry. And when he ran for president, his core message was that tariffs would give American industry breathing room to grow by blocking foreign imports.

By the time he became president, however, McKinley had developed a paradoxical love of trade. As he told the Commercial Club of Cincinnati on the campaign trail: “It should be our settled purpose to open trade wherever we can, making our ships and our commerce messengers of peace and amity.”1

McKinley started relying on the other half of his economic plan, the counter-weight to tariffs: Reciprocity.

Reciprocity can be understood, basically, as proto-free trade. Under reciprocity agreements, America negotiated to drop tariffs and duties for certain categories and goods from a specific trading partner in exchange for the other nation doing the same. In his first term, McKinley’s Republican administration raised tariffs, yes, but it also signed 17 treaties to drop tariffs altogether with various friendly nations. (Although, largely for goods which didn’t threaten domestic American production.)

McKinley’s biggest problem was that he had primed the pump so aggressively against trade that few in Congress wanted to sign these deals. When one particular arrangement with France hit the rocks, his senior trade advisor warned that without the French market for American goods they would see “the usual closing of factories and disaster."

That advisor, who would eventually resign in frustration, tried to appeal to the American entrepreneurial spirit: “We are not regulating an old trade and market, but making a new one for American manufacturers,” he wrote.

By the time he was re-elected to a second term, McKinley was clearly frustrated with the lack of reciprocity. “The problem of more markets requires our urgent and immediate attention,” he said in a landmark speech in Buffalo. More trade was "the natural out-growth” of American industrialization, he said. McKinley called for the building of a merchant marine, new telegraph cables, and for the completion of a shipping canal in Central America. Isolationism was over.

McKinley hadn’t entirely forsaken his belief in protectionism. But he had set a clear course: America would be a trading nation, not an insular one.

The next day, McKinley visited Buffalo’s Pan-American Exhibition to shake hands with the attendees. More than that, he was boosting a mission of hemispheric cooperation — just the day before, he toured the Niagara Falls, casting an eye to America’s neighbor.

Amongst those who lined up to greet the president was Leon Czolgosz. When he reached the front of the line, the anarchist pulled out a pistol and shot McKinley at point-blank range.

With McKinley’s death, interest in reciprocity waned. America signed just two such trade agreements in the decades to come: One, with Cuba; the other, with Canada. That was no easy feat, as “protectionists of all stripes also feared that Canadian reciprocity would be a major breach in the tariff wall, allowing Great Britain to flood the American market,” historian Tom Terrill wrote. One of McKinley’s predecessors, President William Henry Harrison, had mused that a trade agreement with Canada would be impossible without “an absolute commercial union,” at the very least and likely not unless it was “accompanied by political union.”

In 1930, protectionism had one last hoorah with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. It erected trade barriers with the whole world, Canada included, prompting a global trade war. Just as imports and exports plummeted, America sank into the Great Depression. While the tariffs didn’t cause the economic turmoil, economists have argued, “they nonetheless had a significant, recession-sized impact, ‘small’ only in the context of the Great Depression.”

It would take Franklin Delano Roosevelt to finally open America to the world for trade: And usher in a new era of prosperity.

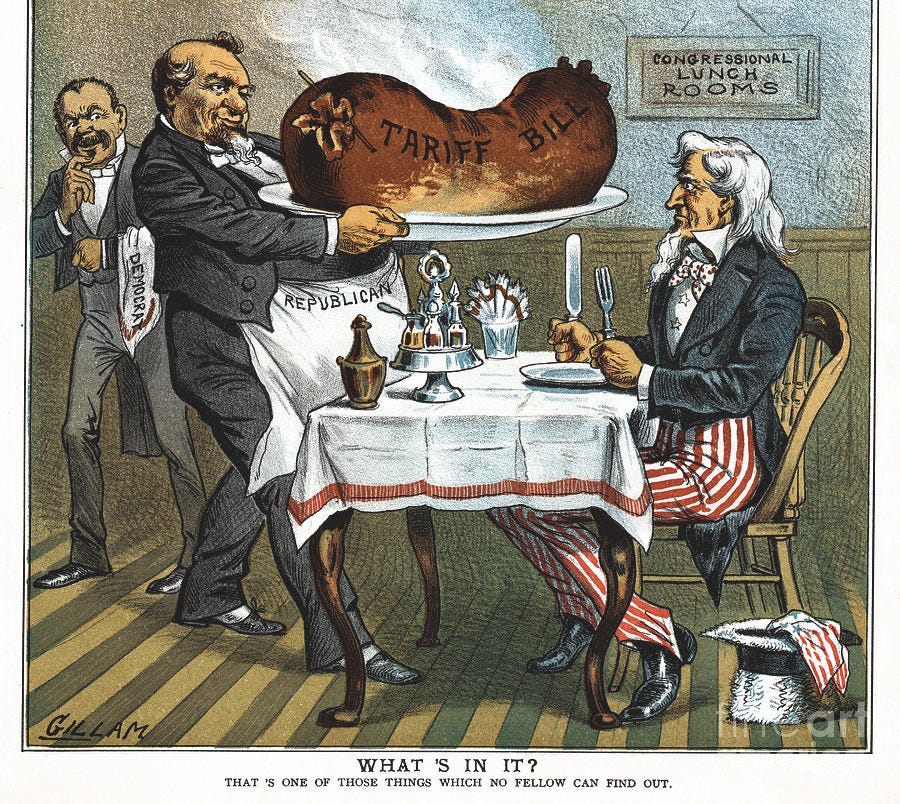

McKinley’s epoch of protectionism became a relic of history almost immediately — perhaps even before it truly ended. An exasperated editor is said to have remarked in 1894, before McKinsley even became president: "If anyone says 'tariff' to you, shoot him on the spot."

This era of sky-high tariffs and protectionism would remain largely forgotten, criminally under-studied by historians, until the election, and then delayed re-election, of Donald Trump. In January, the president signed a declaration declaring that McKinley “championed tariffs to protect U.S. manufacturing, boost domestic production, and drive U.S. industrialization and global reach to new heights.” And he honored that legacy by threatening to tariff the world.

This week, on a very special Bug-eyed and Shameless, a conversation about tariffs. More particularly, about the crackpot economics that brought back protectionism’s friendly hand.

I write to you from trade war limbo.

As you’re no doubt aware, President Donald Trump abruptly threatened to slap 25% across-the-board tariffs on Canada and Mexico last month, with similar trade barriers planned for Europe, only to pull up at the last minute. Citing border plans (which both countries already had in place) the president claimed temporary victory and suspended the tariff plan for 30 days.

And then, just as everyone un-clenched their teeth, Trump announced fresh 25% steel and aluminium tariffs.

In the chaos of recent weeks, there have been plenty of competing explanations for why Trump has sabre-rattled for economic warfare with his ostensible allies.

Does Trump actually want to make Canada the 51st state?

Is Trump really trying to stop the flow of fentanyl into America?

Is this about immigration?

Defense spending? A personal grievance against Justin Trudeau? An attempt to sow chaos?

It is all of those things, to varying degrees.

But we can’t ignore the simple fact that Trump loves tariffs. Why he loves them so much, and the strange circuitous path to how he got there, can tell us a lot about the coming four(?) years. And how this term differs from his first go ‘round.

Just Say No To Mercantilism

When Peter Navarro ran for mayor of San Diego, he did so as a maverick.

A Democrat-turned-Republican-turned-independent, his grassroots campaign turned heads. His team lacked the usual campaign consultants which, by 1992, had become the norm in American elections at all levels. Instead, the economics professor was surrounded by other middle aged white dude academics.2

He had risen to fame in the city by becoming its chief NIMBY, railing against the “Los Angelization” of San Diego. As a candidate for mayor, he wanted to cap that number of homes built and jack up fees on businesses and developers. He was anti-growth but pro-jobs, anti-union but pro-labor. He wanted to link the city more with Tijuana, endorsed gay marriage, pitched himself as an environmentalist, and wanted to allow needle exchanges.3

His critics called him a demagogue and a chameleon. They seemed to be right. He was also weird. When the city organized an all-candidates debate on the waterfront, Navarro decided to get there by swimming. (His chief rival, clearly off-put, hired a gang of rival swimmers to race him there.) But so sure was Navarro that he plowed hundreds of thousands of dollars he inherited from his parents into the race.

He surprised the establishment when, in the open primary, he came ahead of the presumed frontrunners by a mile. In the run-off, he fell behind the establishment Republican by about four percentage points.

When America tilted right in 1994, Navarro went the other way: He went back to being a Democrat, and ran for Congress. He lambasted those who would “cynically ride a tidal wave of white male rage and anti-immigrant fervor right down the Potomac and into the White House.”4

Navarro ultimately lost four elections in a row, never quite reclaiming the glory of his mayoral bid, before he finally hung up his electioneering hat. Instead, Navarro began writing pulp financial advice books: What the Best MBAs Know, When the Market Moves, Will You Be Ready?, If It's Raining in Brazil, Buy Starbucks and so on.

In 2006, Navarro published The Coming China Wars. It was his transition from pop financial advice into the world of real economic policy. And, really, it’s not a bad book. Much of what Navarro warns of ended up being spot on. His solutions are as sage now as they were then: Spank China at multinational fora like the World Trade Organization; set environmental standards to block China’s polluting goods; take Beijing to task for dumping the precursor chemicals for narcotics into North America; oppose the Communist Party’s debt colonialism in Africa; invest heavily into alternative fuels to break America’s dependence on foreign oil; and consider stripping China of its veto power at the United Nations.

Navarro even compared China’s unfair trade practises to America’s own obsession with tariffs, noting that Washington’s early 20th century trade barriers “helped cause the Great Depression.”

Many of these observations were quite novel for the time. Most Western leaders saw only riches, cheap labor, and success through cooperation with China.

Reviewers didn’t appreciate it. One sniffed that it was a “hyperbolic, often hysterical, book.”5 Another turned their nose up at its “sensationalist tone.” A Sino-watcher was even more caustic: “This book is a collection of the worst news stories that the author could find followed by a list of ideas that was most likely generated on the blackboard at the end of a college IR class. Don’t waste your time or money.”

Navarro returned to the policy arena in 2010 with Seeds of Destruction, a book lamenting America’s inadequate 21st century growth. He and his co-author skewer America’s trade deficit. When America buys more from other countries than it sells “these other countries enjoy the benefits of increased jobs, wages, and GDP growth” while America gets nothing.6 Years on, this would be a core assertion of Donald Trump’s re-election campaign.

But, still, Navarro remained within economic orthodoxy. In the mercantilism of yesteryears, he writes, European nations “sought to accumulate as much bullion and trade surpluses as possible by using a combination of tariffs to protect their own markets and subsidies to promote their exports. Of course, the results of these ‘beggar thy neighbor’ policies more often were war and turmoil rather than economic prosperity.”

He, again, prescribes some fairly rational policy ideas. Get off foreign oil, improve the tax code, run a consistent monetary and fiscal policy, boost exports through strong domestic growth; and pass an act codifying fair trade. He explains that last bit:

Navarro: Any nation wishing to trade freely in manufactured goods with the United States must abandon all illegal export subsidies, maintain a fairly valued currency, offer strict protections for intellectual property, uphold environmental and health and safety standards that meet international norms, provide for an unrestricted global market in energy and raw materials, and offer free and open access to its domestic markets, including media and Internet services.7

Navarro was carefully avoiding caricaturization as a protectionist.

A protectionist would say that the simple act of selling goods from a low-income country into a high-income one is one that deserves a tariff — the import duties would offset the difference in wages.

But Navarro is arguing that a tariff can simply be a calculation of the various nefarious practises employed by the exporter — in China’s case, that involves considerable subsidies, wanton environmental destruction, forced labor, and an artificially-depressed currency. Follow the rules, Navarro argues, and you can enjoy tariff-free market access.

There are implementation problems with this tactic, but it remains a perfectly valid and thoughtful approach to globalization.

When it came to America’s other high-income trading partners, Navarro didn’t take much of an issue. “While there remain some problems in trade relations between the United States and the Eurozone, Japan, Mexico and Canada,” he writes, “these problems are minor compared to the protectionist and mercantilist practices of China.” The trade deficit with Canada, in particular, was illusory, he said, as it was largely the result of the cross-border flows of oil.

But Navarro’s politics were shifting, sometimes they seemed to change as he was writing his books. He began warning that all imports from the Global South inherently “depressed wages and materially reduced the standard of living of millions of Americans.”8 He started to warn of a future where China’s massive U.S dollar reserves could be used to “purchase or gain controlling interests in American companies and then strip these companies of either their technologies or jobs, or both, further weakening the U.S. economy and manufacturing base.”

Whereas just years earlier he had lamented how tariffs triggered the Great Depression, he began calling that accusation “so much cow manure” but “undeniably potent propaganda.” He began writing overt defenses of protectionism.

He cemented himself as one of the most popular China hawks in America when he published Death By China in 2011, along with an accompanying film. That book, supposedly, made a big impression on Donald Trump. (More realistically, it was identified by son-in-law Jared Kushner while he was searching for books critical of China on Amazon.) When he launched his 2016 presidential bid, Trump tapped Navarro as an advisor.

It was on the campaign that Navarro completed his turn from a China-skeptic fair trader to a full protectionist. In a position paper co-authored with fellow Trump advisor Wilbur Ross, Navarro declared that “Trump will end, not start, a trade war.”

Navarro, king of the 180-degree turn, was suddenly chiding NAFTA as a “bad deal.”

This wasn’t just about China anymore. Looking at America’s trade deficit with Canada, Germany, Japan, Mexico, and South Korea, a Trump administration would have a clear objective: “Increased exports and reduced imports.”

To Be Constrained by the Notions of How Things Are “Supposed” To Go.

Donald Trump’s shock election in 2016 left his team with a perplexing problem: What did they actually want to do?

His hodgepodge team had anti-trade hawks, like Ross and Navarro, who was tasked with setting up some nebulous trade committee. But there were free-traders, institutionalists, and globalists, too, like trade representative Robert Lighthizer and economics czar Gary Cohn.

In a retrospective of his time in the first administration, he pens one illustrative dramatic scene.

Cohn: Mr. President, you have to understand that if you put these tariffs on, that is going to raise prices and endanger our recovery.

Navarro: Boss, we ran on tariffs in 2016 and the frigging Koreans and Chinese are cheating like crazy. It’s just off the charts. Your Trump tariffs are perfect for this situation.

The Boss: He’s right (looking at Gary and pointing to me). We need to get on with it.

Cohn: But, sir, this is going to raise consumer prices.

The Boss: Can you believe this globalist? (Looking at me.)

Navarro: Unfortunately, I can, sir. He’s your hire but he’s been my problem.

The conflicts at the king’s court really came to a head in the fight to replace NAFTA. (Emphasis mine.)

Navarro: A few days after the election, Wilbur Ross and I began some quiet and delicate negotiations with several high-level Mexican diplomats regarding the president-elect’s ironclad promise to quickly renegotiate NAFTA—the North American Free Trade Agreement. Wilbur and I both liked the idea of beginning with the Mexican side for several reasons.

First, it was in Mexico where far too many American jobs had been offshored because of the unbalanced nature of the NAFTA agreement. Key aspects of NAFTA had also helped spark a wave of illegal immigration into the US. So the biggest problems with NAFTA were with the Mexico side.

The second reason why we liked to deal with the Mexicans first—and Wilbur knew this better than I did at this point—was that the Canadians are exceedingly difficult to negotiate with. In fact, I can safely say that of all the diplomats that I came into contact with across scores of countries, the only diplomats who were more treacherous and disingenuous than the Canadians were the Communist Chinese.

Our thinking was that if we could get a deal with Mexico, we could force the Canadians to accept that deal by making the very real, credible threat that we would simply withdraw from NAFTA entirely and sign a new bilateral agreement with Mexico. The Canadian economy would be crushed by any such withdrawal, particularly their auto and steel sectors which were heavily integrated into the US economy through NAFTA.

Working in secret, Navarro, Ross, and two officials from the Mexican government penned a memorandum of understanding which laid out a new path forward for NAFTA: It would require that a substantial part of anything manufactured on the continent would have to be made in America. All that was left was to show it to the sneaky, sneaky Canadians.

But the MOU was deep-sixed by the globalists.

Navarro: That MOU would never see the light of day. One of the folks who would stick a fork in it would be the president’s nominee for United States Trade Representative, Robert E. Lighthizer.

Lighthizer would review the document with nothing but scorn, telling both Wilbur and me about how we knew nothing about how real trade agreements were negotiated. What Bob himself didn’t understand is how we could do things differently in the Trump administration if only we weren’t constrained by the notions of how things were “supposed” to go.

So Navarro was largely frozen out of the negotiations of NAFTA — what he now declared “a solid 9.0 on the free and unfair trade Richter scale” beloved on by “metrosexuals like Justin Trudeau of Canada.”

The negotiations began, then crawled forward, then stopped entirely. Trump slapped 25% tariffs on steel and aluminium as punishment for the slow pace of talks. A deal was reached, eventually, in late 2018.

But there’s a crucial moment, here, that is under-appreciated. In his book, Navarro talks about the aftermath of that deal — and the automatic assumption that America would drop its tariffs on Canada.

Navarro: To my deepest regret, it would take the gutting of our steel and aluminum tariffs by United States Trade Representative Bob Lighthizer to get the new United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) to the finish line. The primary problem with getting to “yes” on the USMCA was with the hardliner Canadians—their hidden agenda was to keep NAFTA just the way it was because, at least for them, NAFTA was like legalized highway robbery of American auto workers, steel producers, loggers, dairy farmers, and the American economy writ large.

Navarro wanted to sign USMCA and keep the tariffs. It was no longer about reciprocity, but it had become beggar-thy-neighbor. Navarro, as we know, lost this fight. The tariffs were removed. And, he argues, that cost Trump the 2020 election.

Navarro: Lighthizer’s sacrifice of the steel and aluminum tariffs to get to a NAFTA “yes” would, however, turn out to be a very bad MAGA trade-off that would inflict great cost and pain in Blue Wall country. It likely cost us swing blue-collar votes in several key battleground states where the alleged Biden victory was very narrow.

This book, subtitled Why We Lost the White House and How We'll Win It Back, was written for an audience of one: Trump. At points in the book, Navarro even addresses him directly. (“And, Boss: How about establishing a Lindsey Graham-free zone at Mar-a-Lago, Bedminster, and all Trump golf courses,” Navarro writes.)

Navarro’s whole book is a series of personnel recommendations to the president — many of which he’s heeded.

Throughout the book, Navarro holds up tariffs as a magical policy prescription. They create jobs, boost GDP, bring back factories, and win elections. While Navarro would go on to join the Big Lie, in insisting that Trump won the 2020 election, in this book he accepts Trump’s loss: And blames it on the president’s inability to get enough tariffs done.

Navarro’s most recent book, published just before the election, is advertised as a “deplorables guide to Donald Trump’s 2024 policy platform” — and more particularly, a guide to the “action, action, action” agenda that will be unleashed if he won. In particular, Navarro takes a cue from McKinley: Back in office, Trump would prioritize trade reciprocity, setting American tariffs to match any similar tariffs set by another country. These retaliatory tariffs, Navarro wrote, would be ”a sophisticated and targeted tool to force other countries to lower their tariff and nontariff barriers.”

In a forword, Steven Bannon celebrates Navarro as champion for all the good stuff: “Tax cuts, tariffs, manufacturing renaissance — growth, growth, growth.”

Some Light Trumpology

In recent weeks, Trump has insisted that he's taking his cues from McKinley. He's not. He's taking them from Peter Navarro.

Navarro comes from an orthodox school of economic thought. He knows that tariffs are a destructive economic weapon that do economic harm in both directions. But, over time — and on his journey from punchline to policy advisor — he came to view tariffs as a panacea. They were not just a tool to constrain China and onshore manufacturing, but the vehicle through which we can arrive at fair trade and stick it to the globalists. The tariffs became the message.

The only reason that Navarro did not inflict this quack form of economics on the world in his first stint in office is because the enemies of tariffs kept winning out. From Gary Cohen to Steven Mnuchin to Rex Tillerson: Names of a bygone Trump era who are now only relevant as a cautionary tale of who not to be.

There are no longer moderates, free traders, and globalists in Trump’s midst. There are only radicals, sycophants, and protectionists.

Robert Lighthizer, who was still on the more protectionist side of Trump’s cabinet, was tapped to return to the White House — but the invitation never came. Interesting, then, that just days after Trump’s inauguration, Lighthizer sat down with the New Yorker to profess his sudden affinity for tariffs and protectionism, as if to say: Hey, I’m onboard, bring me back.

Over the past three weeks (yes, it’s only been three weeks) the Trump administration has done its best to move fast and break things. They have clearly succeeded on some fronts, while institutional resistance is holding on others — for now. It is impossible to know what he’ll do next, and that’s the point.

They have been able to move this swiftly and decisively because they are no longer racked by indecision and competing viewpoints. The people around Trump are all firmly in a MAGA mood. Some are radical ideologues. Others are playing characters, willing to do whatever it takes to amass more power. All of them, I think, are informed by their grievances.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr, for example, seems determined to inflict retribution on the scientists and civil servants who, he thinks, peddled dangerous vaccines on the public — and on everyone who told him he was nuts for warning about it.

Kash Patel is going to lay waste to the FBI as punishment for their role in investigating Donald Trump and his merry band of putschists. He will make this as performative as possible, to satisfy the hordes of aggrieved.

Peter Navarro is hitting back at the establishment and elites who thwarted his bids for public office and discredited his writing.

At the top, of course, is Trump himself: The grievance master. Never much of a policy wonk or an actual strategist, he is a masterful collector of grievances, an encyclopedia of those who have wronged him.

We will see these grievances get settled in strange and unsettling ways. But rest assured that the economic slights will be righted with tariffs.

In January, I wrote about how much of Trump’s politics are designed to make others’ dance for him. (Dispatch #123) As I argued, I think it explains his performative obsession with seizing Greenland — that’s true too, I think, for his repeated entreaty to make Canada the 51st state. In both cases, he may well be serious about wanting to seize more land, but there’s zero indication that he’s willing to do the tough and difficult things necessary to make it happen. So he’ll just keep repeating the demand until he gets other things he wants.

The threat of a neo-manifest destiny is real, but the intent to follow through is not.

The follow-through on these tariffs, though, I think is very obvious. As I write this, Trump just announced new 25% steel and aluminium tariffs for the whole world. And, sure enough, the White House is phrasing these tariffs as reciprocity.

"And very simply,” he said, “it's: If they charge us, we charge them.”

Does it matter that 100% of non-agricultural trade between America and Canada is duty-free? (And upwards of 97% of agricultural trade.) Of course it doesn’t matter. This isn’t about emulating the fallen McKinley.

This is about reciprocity. Because reciprocity, in a way, is just retribution.

That’s it for this dispatch!

Apologies for the slow pace of newsletters thus far in 2025. Other assignments and travel, plus a minor surgery, kept me away from finishing this dispatch before now. I’m climbing back into the saddle to fire off more regular newsletters amidst the current chaos.

Keep an eye on my bio pages at WIRED and Foreign Policy this week, as I’ve got some exclusive stuff coming about the state of the incoming cabinet and the U.S-Canada relationship.

The Tariff, Politics, and American Foreign Policy 1874-1901, Tom E. Terrill (1973)

The Los Angeles Times, Sep 27, 1992

The Los Angeles Times, Apr 26, 1992

The Los Angeles Times, Jun 21, 1995

Book Review: Peter Navarro, Gerald Horne. (Cultural Dynamics, 2007)

Seeds of Destruction, Peter Navarro and Glenn Hubbard. (2010)

Death by China: Confronting the Dragon – A Global Call to Action, Peter Navarro (2011)

Manufacturing a Better Future for America, Alliance for American Manufacturing. (2009)

Thanks for this portrait of Navarro, Justin. I always thought of him as a nutbar (i.e., fitting in well with the current Trump crowd) but now I know that at one time he was able to think straight. Depressing all the same, like almost everything else related to the USA these days.

This was amazing, Justin. Before reading it, I was going to contact you to suggest you write about who is really behind all this nonsense, as we know Trump’s focus isn’t on anything other than himself.