Alt-Social Media

New data shows 6% of Americans are regularly getting their news from Gab, Parler, Rumble, Truth Social, and Bitchute. Is that such a bad thing?

“Good morning to everyone — just so you know — nothing's going to happen to dirtbag Hunter or anyone in the garbage Biden family,” @catturd wrote this morning.

“That would require equal justice — which we no longer have in this communist, Democrat-run banana republic.”

That post went out to the anthropomorphic cat’s 816,183 Twitter followers, 700,554 boosters on Truth Social, and 379,488 Gab fans.

The replies on each platform are a paragon of online civility. Supportive memes, friendly banter, and lamentations that there wasn’t more @catturd.

Check the comments on Gab, however, and there’s a particularly unique flare.

There is, for example, the user who scoffs at the idea that Democrats are uniquely to blame — they share an infographic asking “who controls the parties?” The answer, for Democrats and Republicans alike, is: The Jews.

Another posted a meme of their beloved @catturd, adding “FUCK ISRAEL.” Their username contains the two runes which compromise the logo of the Nazi Schutzstaffel.

Perhaps the only unfriendly comment came from one particularly direct user: “Maybe you should stop being a faggot and name the jew already.”

Gab, Parler, Truth Social, Bitchute, Rumble, Odysee, Telegram: They are part of the new internet infrastructure. Their users are increasingly unplugging — or getting banned — from the major social media platforms. And they are fuelling a new generation of digital paranoia.

New data from Pew Research reports that 6% of the United States regularly gets their news from these alternative, “free speech,” far-right platforms. And that number is likely to grow.

This week, on Bug-eyed and Shameless, we’re digging into the bug-eyed internet.

Close your eyes and imagine a typical timeline on your various social media pages.

If you’re anything like me, you conjure up a Facebook page with inane updates from friends you haven’t spoken to in years; a Twitter scroll full of wonky news and political bickering; and an Instagram feed with friends and influencers who look like they’re constantly having more fun than you.

There’s a reason why those platforms have, despite some users unplugging, managed to stick around this long. When Facebook became a hotbed of political chicanery, the platform decided to emphasize real news over political advertising. When Twitter became a trollfest, they introduced an algorithmically-generated timeline and quality filters. When Instagram became a place to dump professionally-shot and highly-edited photos, they introduced stories to create a veneer of authenticity.

Plenty has been written about the slow decay of those platforms.

But those measures that were taken to preserve the interest of the grand majority — banning racial slurs, booting off QAnon, turfing the president, suspending those who share fake news, limiting the reach of more toxic pages — had a knock-on effect.

While these social media platforms were originally written off as havens for Nazis, like Twitter clones Gab, Gettr, and Parler; chock-full of conspiracy content and anti-vaxx nonsense, like video platforms Rumble and Bitchute; and a barely-functioning piece of technology set up solely to make the former president feel important, like Truth Social — they are now established in a way few of us full expected.

Pew reports that 6% of those surveyed reported that they regularly got their news from at least one of those “alternative” social media platforms. Extrapolating out, we’re talking about 20 million Americans who not just use these platforms, but use them regularly. (Which, based on my own experience on these platforms, is a pretty likely baseline.)

The survey canvassed over 10,000 Americans, but there’s little doubt that a cohort of these users who would never tell a pollster of their love for Gab.

Outside the users of these sites, Americans are totally befuddled. Parler had the highest name recognition of any of these alternative platforms, at just 38%. Truth Social, despite being Trump’s preferred bullhorn, clocks in at just 27%. Only 7% of respondents recognized Bitchute.

For that 6% who live on these platforms, however, their reasons for logging onto these websites are quite interesting.

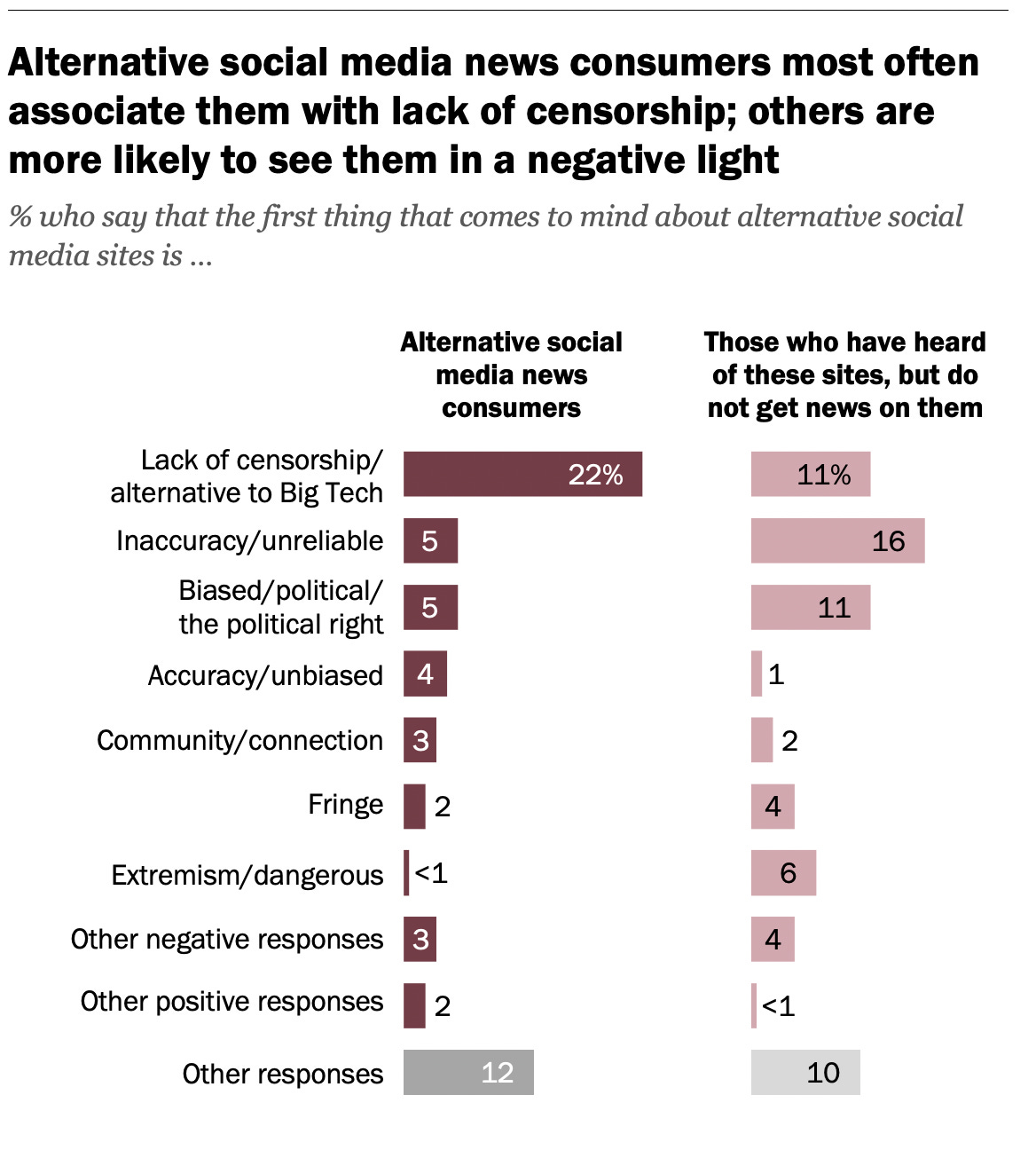

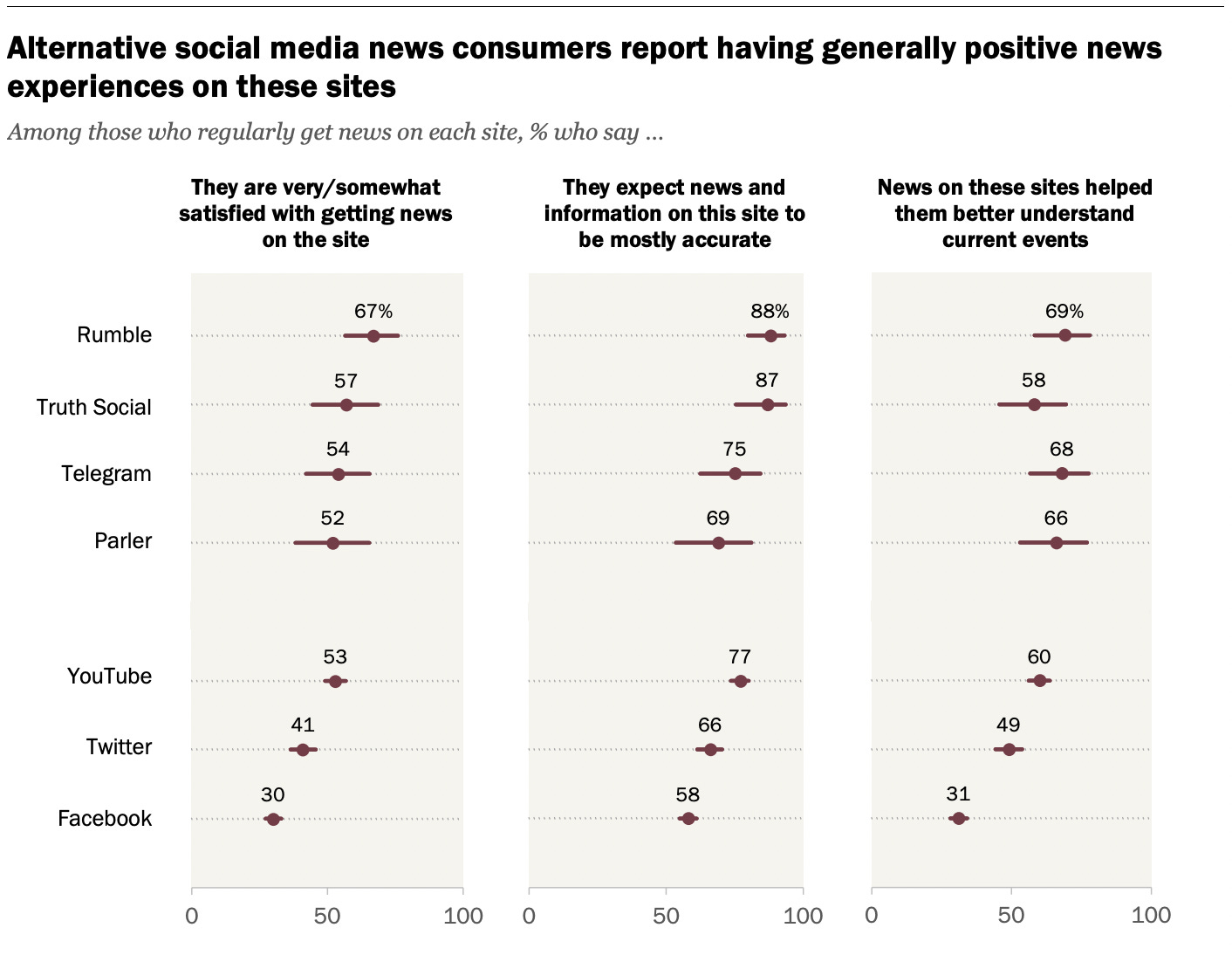

Users were overwhelmingly fond of the idea that these websites did not censor their opinions, and didn’t seem too concerned with the idea that the news and information found on these platforms could be unreliable or outright false.

Whilst party affiliation is not the most useful metric to understanding these platforms — the idea that both parties are corrupted, perhaps by the Jewish cabal, is a common one on Gab in particular — Pew nevertheless found about two-thirds of these alternative social media users identified as Republican, compared to just over a third on other, traditional, social media.

Pew didn’t just canvas users, but conducted an analysis of more than a half-million posts made by 1,400 prominent accounts on these platforms. (Interestingly, it found that just 15% of those users had been banned or demonized on other major social media platforms.)

That analysis reveals what I’ve been writing about in this newsletter for some weeks now: Fringe internet users, conspiracy theorists, anti-vaxxers, QAnon types, they aren’t just having a separate conversation from the rest of us. They are adopting their own language.

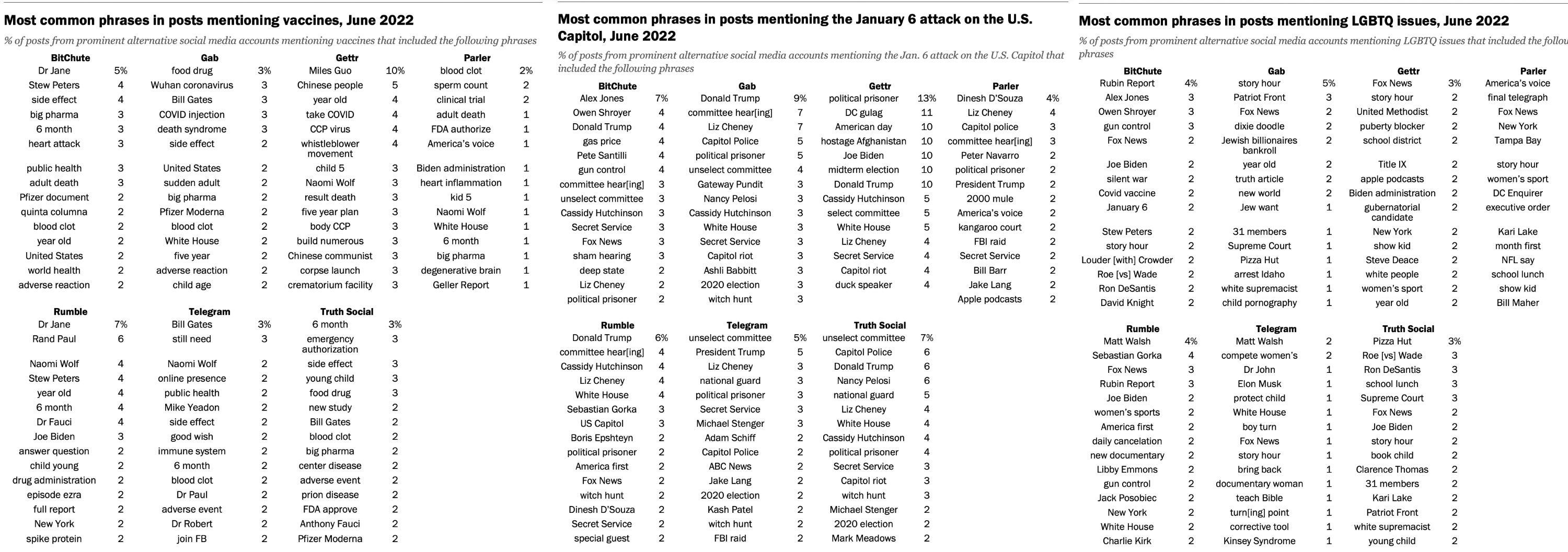

The discussion around these issues often reflects fringe and controversial worldviews on the political right. For instance, some of the most common terms in posts about the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol include “political prisoner,” “DC gulag,” “unselect committee,” “witch hunt” and “sham hearing.” Meanwhile, posts about vaccines indicate a deep and consistent concern about the impact of vaccination. These posts regularly refer to a small group of influential vaccine skeptics. The most common terms in these posts point to a widespread fear of real but rare impacts of vaccination (“side effect,” “adverse reaction,” “blood clot,” “heart inflammation”) but also diseases or symptoms for which the medical literature finds little evidence of being tied to vaccines (“[sudden adult] death syndrome,” “sperm count”). And posts about LGBTQ issues commonly referred to drag queen “story hour” (a common target of anti-LGBTQ groups) or derisive allegations toward gay and transgender individuals, such as “pedo” and “groomer,” implying that they prey on children

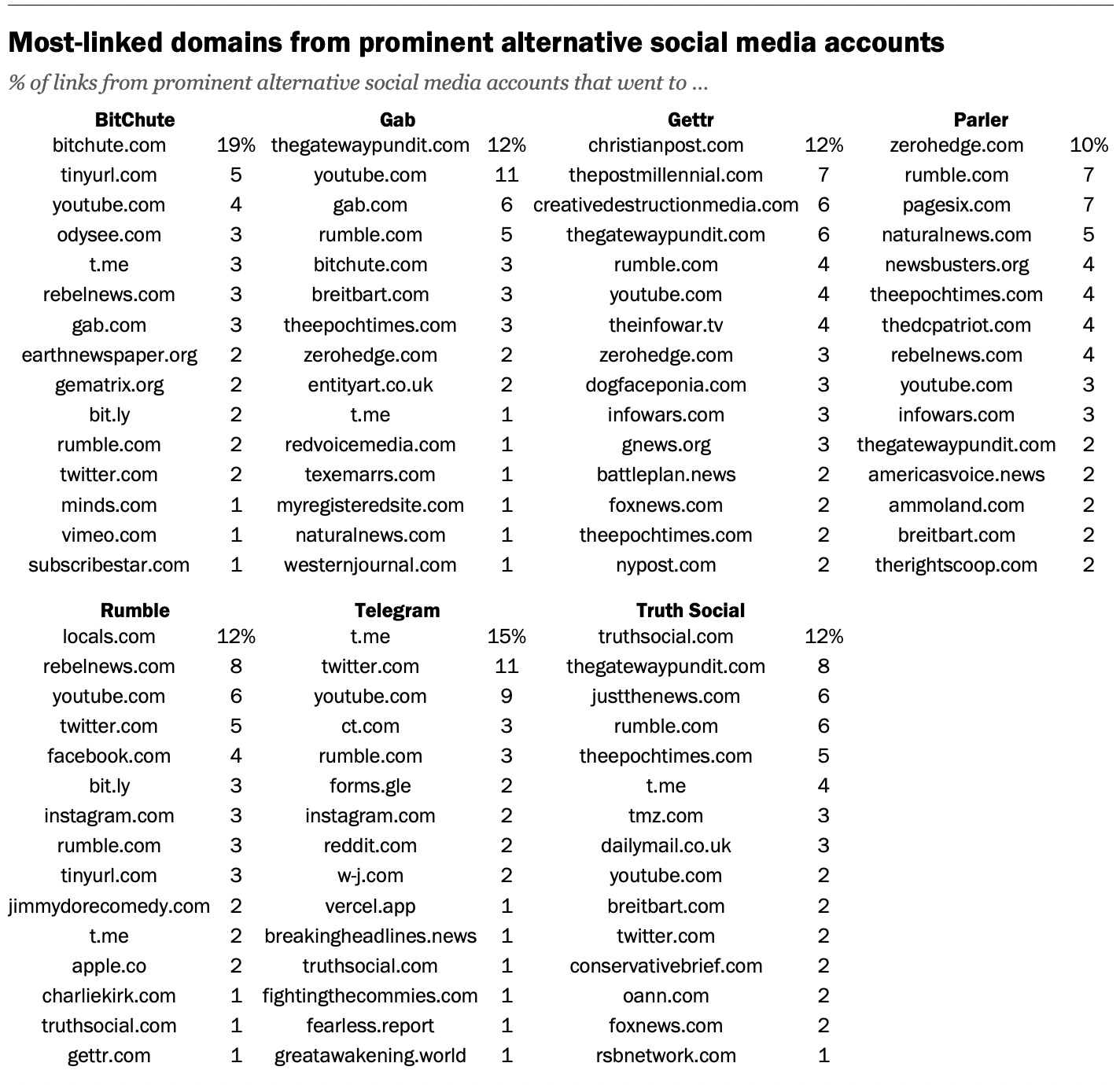

We often talk about this right-wing internet being an “ecosystem.” Pew’s analysis shows exactly what that looks like: While there is still linking-out to major social media platforms and reputable news outlets like the Wall Street Journal, you’re seeing an entirely new news diet emerge: One that relies on conspiracy outlets like The Gateway Pundit, The Epoch Times, and Infowars.

The significant amount of traffic and demand in this space is crowding new participants into the market. I, as you can probably appreciate by now, spend far too much time on these platforms — I can’t even begin to keep up with the number of new podcasters, streamers, radio hosts, and influencers who are breaking into this space. Even on the Pew-supplied list below, several of these links were totally new to me.

It’s easy to write off these platforms as refuges for political dissidents — people who are either so enamoured with their own worldview that they can’t tolerate to be surrounded by contrary opinions (i.e. they need a safe space) or toxic trolls who demand the right to espouse racist, homophobic, sexist, and otherwise unpleasant ideas and words. They certainly are that.

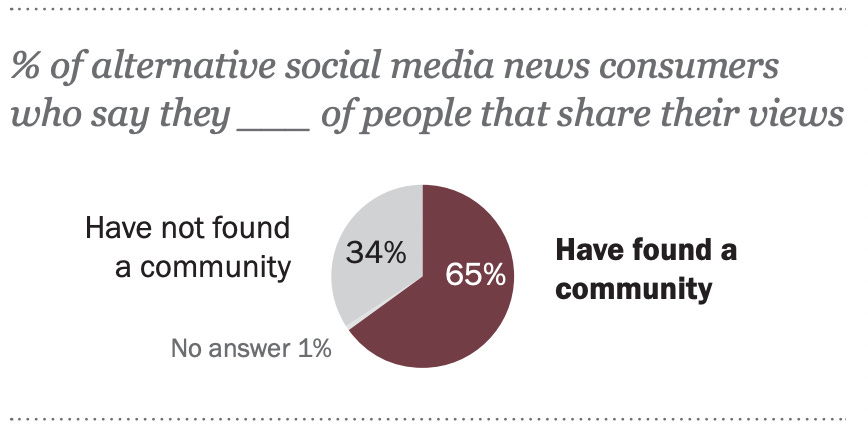

But they are also communities. Many users log on every morning, excited to see what @catturd has to say. There are rolling discussions amongst people who recognize each others’ screen names. Users speak to each other via mutually intelligible references and memes that would be inscrutable to the public.

These alternative platforms are not, in and of themselves, a problem. A greater diversity of options on the internet is probably a good thing.

The issue is that these social media outlets are built explicitly to, at best, tolerate hate, paranoia, and radicalization and to, at worst, actively encourage it. The end result is people spending large parts of their day consuming content that tells them Jews run the world (and, I suppose we are to infer, doing a bad job of it), that a coordinated replacement of white people is designed to destroy their political power (Bug-eyed and Shameless #2), that the vaccines are killing millions (BEAS #1), that the World Economic Forum will turn the West into autocratic China (BEAS #17), that Queer people are out to turn the kids trans (BEAS #8) and so on. Those beliefs have regularly broken free of the confines of this ecosystem, and screwed up society for the rest of us.

There are no systems-wide solutions for this problem. These platforms cannot be regulated out of existence, nor should they be. Indeed, their very essence is rejecting censorship — real and perceived. If one government moves to regulate them, or any ISP tries to drop them: They will move somewhere more friendly. (Parler has already had to do this.) Any increased regulation on Twitter, Facebook, and elsewhere will almost certainly drive more users to Gab, Telegram, and the like.

On Bug-eyed and Shameless dispatch #20, I wrote about how we need to start thinking about the internet as a physical space if we are going to understand how to break down the walls of this new information ecosystem. This Pew research is a very fine illustration of how these users read the same newspapers, visit the same coffee shops, see the same movies.

There is another side to this coin, however. These Pew data underscore the challenge of reaching the people who have decamped to these platforms. But they might also be predictive of where the rest of us are going.

Increasingly, users are disengaging from the major platforms — not because they stifle free speech, but often because they do too little to manage the toxicity. Or, perhaps, because they have tried desperately to expand into monetizing new features that their users simply do not want.

Whatever the reason, social media is starting to look less like a global platform where everyone is speaking to everyone, and more like a platform of communities and neighbours.

Slack and Substack have become increasingly popular, in a world where people are looking to talk to their friends or colleagues in a closed shop, or where they want their favorite author’s content sent directly to their inbox (hi!)

So this 6%, these 20 million people, they actually enjoy these weird, racist, vile, paranoid, welcoming, friendly online spaces. Yes, these platforms have radicalizing and corrosive effects. But there is a marginal benefit from having a place where these people feel heard and seen, instead of in a massive open space dominated by a small number of giant blue checkmarks.

It’s hard to say where we go from here.

Gab, Parler, and Truth Social are all poorly-run. There has already been a mass exodus from Parler (@catturd has already left behind their 313,000 followers on that site.) Truth Social has been beset by a litany of problems, has been banned from the Google Play store because of the litany of violent threats on its platform, and has kept registration closed to avoid overwhelming the servers.

It’s entirely possible that these platforms will simply crumble, as will their successors.

It seems equally likely we will see an increased balkanization of the broader internet, however. On many fronts, that will be a welcome change.

If that does happen, if we do we retreat into our own little caves, it’s hard to say whether that will improve this political polarization or make it worse. In the most optimistic scenario, arranging the internet more by smaller communities of interests — like it used to be — could remove politics as a more central rallying point online and create friendlier, less combative online spaces. In the worst case scenario, we all burrow into our dens, retreat from broader society, and radicalize each other, creating a thousand little networks of unrelated conspiracy theories and deranged grievances that, back in the real world, further make nation-state politics untenable.

Hopefully it’s the former.

That’s it for this week.

For subscribers: On Tuesday, I’ll be test-driving an open thread, where you can all chime in — with suggestions for future newsletters, criticisms, comments, questions, recommended reading, etc.

Until then.

Does @catturd have a running mate for 2024 yet?