A Year of Ukrainian Innovation

For 12 months, Kyiv has been on a mission to invent technology on par with gunpowder. Has it succeeded?

Emperor Xianzong of Tang was determined to live forever.

A veritable army of alchemists were dispatched to come up with a nostrum which would please the emperor. They mixed tonics with white lead and arsenic sulfide, proffering them to their ruler, hoping it was the right concoction to grant him eternal life.

They, as you can guess, didn’t work. But they did give him bleeding gums, fever, bloody vomiting, and insanity. You did not want to be one of the eunuchs serving the emperor in the latter years of his reign, in the early 9th century. When the emperor died suddenly, recriminations flew: But many suspected he was felled by his own arrogant quest for immortality.

Some three decades after his death, a text bearing the wonderful title of “Classified Essentials of the Mysterious Tao of the True Origin of Things” revisited the emperors’ dalliance with alchemy. One by one, the book debunks the elixirs as quackery. The book’s author warns of one mix in particular.

“Some have heated together sulfur, realgar and saltpeter with honey,” the book reads. “Smoke and flames result, so that their hands and faces have been burnt, and even the whole house where they were working burned down.”1

Saltpeter had been in application in China for years — they discovered it in the decay of organic matter, and cooks used it as a flavorful additive. We know it better today as potassium nitrate. Mixed with sulfur, as they did, the Chinese chemists had inadvertently create a prototype of “fire drug.”

“When the two super-natural elements, Yin and Yang, meet each other in an exceedingly close space,” another text from the time reads, “the resulting explosion will stun every soul and shatter everything around it.”

At first, this new fire drug was largely used for a bit of innocent magic. A poof of smoke here, a small pop there. With time, tinkerers discovered that packing this compound into a bamboo shoot, enclosing it, and connecting it to a wick would create a dazzling display, which court pyrotechnics used to entertain Xianzong’s successors.

But this fire drug had also arrived in the hands of the generals. They began using it to pack fire bombs, tip incendiary arrows, and to fill small metal balls that would burn enemy structures. Deployed for the first time, it spooked marauding enemies but didn’t seem to have much actual effect. Palace scientists kept iterating, even as the Mongols swept their empire. When partisans of the Ming Dynasty confronted the ruling Mongols in 1359, they wheeled out long tubes packed with this fire drug, only to discover that the Mongols had begun employing the explosive mix, too. The fight was a draw.

The Chinese had invented gunpowder, but found themselves no better off for it.

How their invention arrived in the United Kingdom is a long and circuitous route. But in 1346, just as the Chinese were fighting to stalemate against the Mongols, King Edward III equipped scores of his men with gunpowder — some packed into hand cannons, others functioning as larger bombards. These gunners loaded the barrel with a projectile, a stone or a bolt, then packed it with powder. Every shot they fired threatened to explode their novel weapon, and them with it. But it completely changed the dynamic of the fight.

The English had been badly outnumbered, perhaps by as badly as two-to-one. And yet King Edward’s forces massacred the French, taking few casualties in return.

In just a matter of years, these guns — what Shakespeare called “mortal engines” — would grow enormously, and would begin threatening the castle walls which had once protected the European nobles. For centuries, nations’ ability to innovate new applications for this gunpowder would determine whether their dominion grew or fell. These guns would be wheeled onto battlefields, affixed to ships, and slung over musketeers’ shoulders. Gunpowder would spur revolution, enable repression, and fundamentally change war for the rest of history. Alfred Nobel, tinkering in St. Petersburg in the 1840s, would lurch the science of warfare forward by inventing dynamite. Two decades later, Richard Jordan Gatling would find terrifying new applications for gunpowder with his namesake gun, allowing for cartridges of black powder to be dropped into the gun in rapid succession. The winners and losers of 20th century warfare would be decided by who could master innovation in gunpowder and blasting caps.

“The simple fact,” General Valery Zaluzhny told The Economist a little more than a year ago, “is that we see everything the enemy is doing and they see everything we are doing. In order for us to break this deadlock we need something new, like the gunpowder which the Chinese invented and which we are still using to kill each other.”

This week, on a very special Bug-eyed and Shameless, I want to break down how Ukraine’s quest to reinvent gunpowder is going.

If you’re followed my reporting in WIRED at all, you know I’ve become a bit obsessed by this topic over the past year. Ever since Zaluzhny gave that interview, and expounded on it in a corresponding paper, I’ve become fixated on how Ukraine might innovate its way out of this imperialistic war.

I should say: I don’t like war. And that’s precisely why I’m keen on learning how Ukraine might unlock a bit of technology that raises the cost of prosecuting this pointless war, making it untenable.

So this dispatch is mostly just trying to tie together these four lengthy features, all published in WIRED, where I tried to untangle this fast-moving quest to innovate. Plenty of this reporting comes directly from my trip to Ukraine earlier this March, as well as from interviews with many in the Ukrainian defense technology sector, as well as a number of American, European, and Canadian officials.

This is by no means an exhaustive investigation into every aspect of Ukraine’s self-defense, but it does grapple with most of the areas for a possible breakthrough identified by Zaluzhny. But more than just linking to my past reporting, I’ve added some updates, context, and additional information. Below, for paying subscribers, I’ll include some additional thoughts on the state of the war, and what 2025 holds.

To Beat Russia, Ukraine Needs a Major Tech Breakthrough

When Zaluzhny first raised the idea that Ukraine needs a technological innovation no less impressive than gunpowder, his forces were mired in “positional warfare,” as he called it. That assessment provoked some anxiety from President Volodymyr Zelensky — who feared that such a designation was code for “stalemate.” The conversation with The Economist may have been the beginning of the end of Zaluzhny’s tenure as commander of the Ukrainian Armed Forces. He was removed from the job in February.

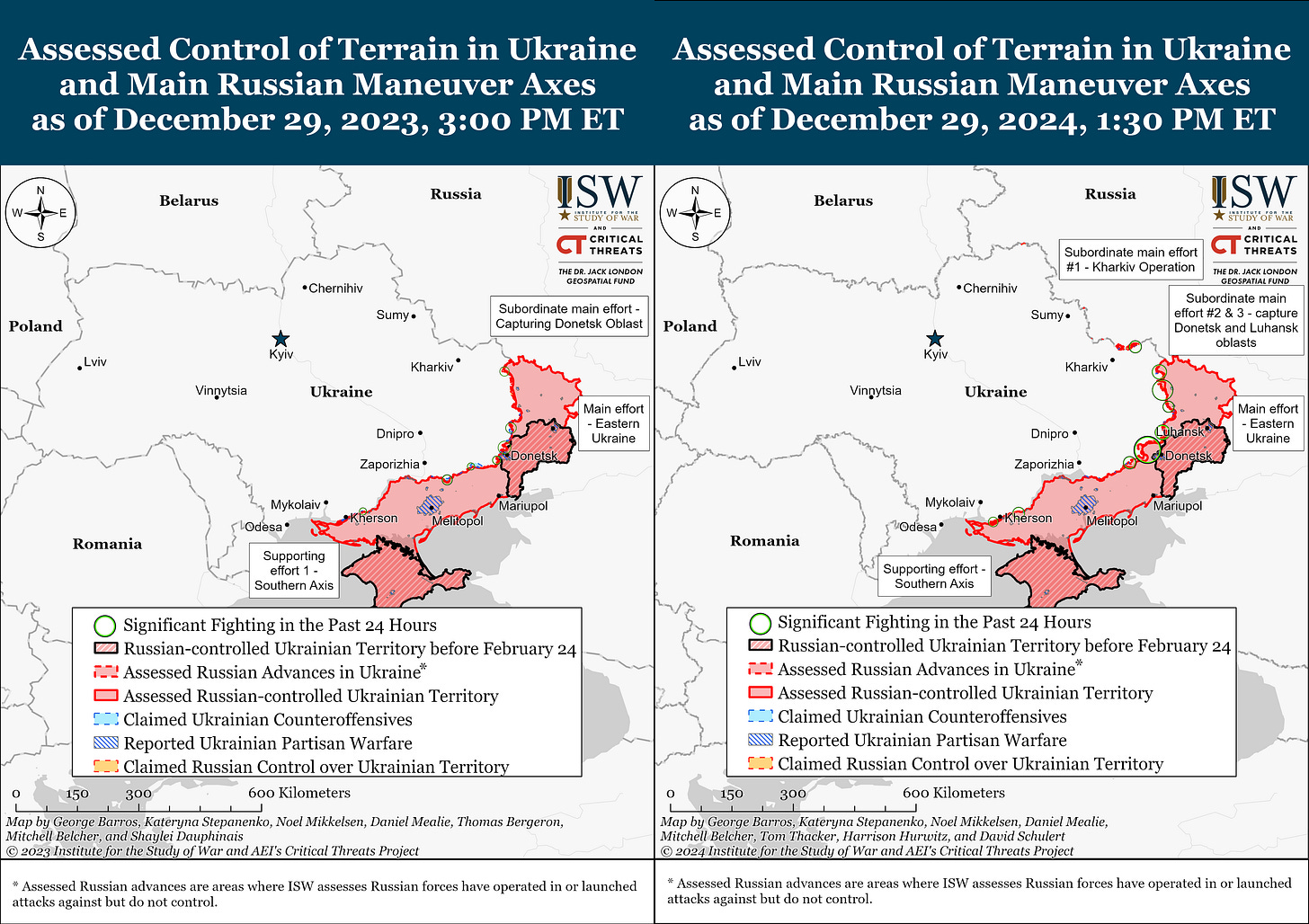

A year on, it’s become quite clear that Zaluzhny was entirely right. While there has been much made of Russia’s marginal gains in the east, particularly around Donetsk; and Ukraine’s stunning landgrab in Kursk, the fact remains that the lines of contact aren’t much different than they were this time last year.

Yes, Russia has managed to push back Ukrainian lines in several areas. Yes, they are bombarding Kharkiv, Dnipro, and numerous other cities and settlements. Yes, the Russian industrial base has stood up in a massive way, enabling a more robust assault than we saw this time last year. But the fact remains that Russia has been largely incapable of achieving its objectives in Ukraine, and is paying an astronomical price for its vain attempts.

One of Moscow’s key objectives in recent weeks has been the seizure of Pokrovsk, a small town northwest of Donetsk. The Institute for the Study of War assessed earlier this month:

ISW: Putin may be pressuring the Russian military command to advance […] to make outsized claims about Russian successes in Ukraine for both foreign and domestic audiences. An organized offensive operation against well-defended towns could slow the rate of Russian advance during a critical moment in the Kremlin's efforts to project the inevitability of Russian military victory on the global stage.

This one axis of combat is an example of how Russia’s attempts to forge ahead may doom their ultimate attempt to regain the initiative in this war. By just about every other metric than square kilometres of land seized, things are going miserably for Russia. The North Korean mercenaries? More than 3,000 of the 12,000 deployed have already been killed or wounded. Moscow’s increased military industrial output? The losses have been so extensive that the Russian Forces still seem to have just half of their pre-war combat vehicle stockpiles. A Donald Trump-imposed peace deal in Moscow’s favor? The Kremlin is already suggesting that it will refuse Washington’s peace plan.

As

explained to me earlier this year: “Maybe Ukraine should embrace positional warfare for the time being. Maybe that is the way it reconstitutes, regains its strength, and thinks through the problems that it has — from the tactical through to the strategic level.” While it would be wrong to paint too rosy a picture, it seems that embracing this break is exactly what Ukraine has done.All told, this was neither a good year nor a catastrophic year for Ukraine. And it gave Ukrainian industry plenty of time to tinker.

The Danger Lurking Just Below Ukraine’s Surface

It may not seem obvious why de-mining efforts would help Ukraine win this war. But there are two good reasons why it’s fundamental.

One is that the parts of Ukraine not occupied by Russia need to become productive again. A year into the war, Kyiv reported that as much as 174,000 km2 of its territory was contaminated by mines. Some of these minefields were laid when Russia occupied the land, others were contaminated by missiles filled with “butterfly mines.” Clearing that land prevents civilian casualties and returns productive agricultural land at a time when Ukraine needs it most.

The second reason has to do with Russia’s defensive lines. Ukraine’s much-vaunted counteroffensive fizzled out in 2023, in part, because Russia was so adept at building trenches, setting up fortifications, and laying minefields. If Ukraine manages to launch a fresh counter-offensive next year — a big if, granted — it will need to be ready to clear lots of land and quickly.

Zaluzhny raised all sorts of possible tech which could achieve this end: LiDAR, a laser measurement system which is increasingly common on self-driving cars and which could be used to detect the mines; a tunnel-burrowing robot which could detect the mines from below; decommissioned jet engines which could explode the mines en masse, amongst others.

Most of the practical solutions which have been developed and deployed over the past year aren’t quite what the general had in mind, but they are nevertheless impressive. Ukrainian-made autonomous land vehicles are already rolling off the assembly lines. Ukraine’s partners have really come through in delivering de-mining systems. Nearly 70 de-mining operators have been certified to assess and clear land of mines, and some 50 more are awaiting approval.

Ukraine has already cleared 35,000km2 of its contaminated territory. This is happening at a speed which nobody predicted.

This has enormous potential for Ukraine, but also for the rest of the world. For decades, de-mining has been a desperately under-resourced field. The innovations taking place in Ukraine right now will have clear benefits for other mine-plagued countries, from Afghanistan to Cambodia.

Inside Ukraine’s Killer-Drone Startup Industry

One of the wildest technological leaps Ukraine has taken has been in the field of uncrewed vehicles. From the land, sea, and air, Ukraine has managed to do enormous damage to its invading enemy without putting its own men and women at risk.

My reporting brought me to some fascinating workshops and makeshift factories hidden around Kyiv: In high-rises, strip malls, nondescript basements, behind false storefronts. I encourage you to read the article, because I think it is a fascinating look at how fast things are changing in this field.

Since I published this article, things have only kept advancing. Just this week, Kyiv test-fired its homemade ballistic missile. Its long-range drones have hit Russian oil depots, ammunition depots, and even their drone factories. New land uncrewed systems have been approved and are being dispatched along the frontlines: To deliver goods, evacuate wounded soldiers, and provide a critical line of sight.

Russia has worked feverishly to keep pace. And, thus far, it has largely succeeded. But there’s reason to think that it is running out of steam.

Russia has upped its production of the Iranian-designed Shahed drones — miserable munitions which have, increasingly, swerved and dipped around the Ukrainian skies, designed to get Ukraine to use up its dwindling stockpiles of anti-air missiles. (I remember being very annoyed by them, sitting underneath my hotel in Kyiv in March.)

But the ISW has recently assessed that “Western sanctions are complicating Russia's ability to source quality components for Shahed drones and that Russia is increasingly relying on low quality motors from [China] to power Shahed drones.” (There’s a reason the Ukrainians call these things “mopeds.”)

NATO is increasingly trying to finance local Ukrainian industry, instead of shipping its own drones over. That is critical in helping Ukraine buy better gear: Upgrading from the cheaper Chinese components which Russia also relies on, opting instead for advanced chips and antennas made in Taiwan, Canada, the U.S, and elsewhere.

The thing to look for in 2025 is which side can network their drone attacks. If Ukraine can figure out how to unleash swarms of drones, connected and operating as a single unit, they will be considerably more resilient against Russian defenses and could do considerable damage. I suspect you’ll hear much more about this very soon.

The Invisible Russia-Ukraine Battlefield

Of all the things I dug into for this series, nothing surprised me more than the wild and technical world of electronic warfare (EW).

Because this war is fought on the invisible parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, it is easily ignored. EW remains a field where Russia maintains a clear upper hand: But where Ukrainian doctrine remains so different, so adaptive, so nimble, and so innovative that it may yet win the upper hand.

This is a tough fight, however. While EW can be used to bring down drones, missiles, and even fighter jets, artificial intelligence is increasingly being used to harden these systems — allowing them to connect to their target, even when they have lost contact with the outside world.

Perhaps the most fascinating thing I learned in reporting this story is that the United States, likely, still has significant EW capabilities that it has yet to deliver to Ukraine. There is some logic to this — once these capabilities are used, it becomes significantly easier to overcome them. But it does make me think that America may yet have the power to change the course of this war.

Below, some analysis and predictions for 2025, just for paying Bug-eyed and Shameless subscribers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Bug-eyed and Shameless to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.