“You law-makers,” Dr. James Richmond says. “You think that four stone walls and a barred window will cure everything or anything. But still you endeavor by law to force a man born with inverted sexual desires, born to make his way in the world with millions of human beings radically different than he is, to become something which his soul will not permit him to become.”

The “born homosexual,” he continues, “is not deliberately vicious.” In fact, Richmond continues, he had seen a patient earlier that day — a born homosexual.

Judge Robert Kingbury is not impressed. “Consider what would happen if this nameless vice were permitted to go rampant in society. How long do you think it would be before it’s degrading, pernicious effect would be felt throughout the very foundations of society?” he asks. “The law has forced this vice into a corner, just as it has forced prostitution into shady byways.”

Richmond shoots back: “Granted the law has done just that, but what specific good has it done?”

Little does the judge know that his own son, Rolly, is — despite being married to a woman — one of these “sexual inverts.” And he is planning a ball for that very night: A drag ball.

The drag queens assemble under the cloak of darkness at the Kingbury manor later that evening, only narrowly escaping a brush with police. One of the queens, Duchess, wasn’t worried: “The cops, they like me. They all know me from Central Park.”

Just the same, when the doorbell rings and the lights go out, cries of “my god, the place is pinched!” go up, and the Duchess and her fellow queens snatch their wigs, lift their rhinestone dresses, and bee-line for the exit.

But it’s not the police — yet. It is Rolly’s old flame, who harbors an obsessive passion for the unhappily married man. He lifts his pistol, shots ring out. A detective is called and the murder is solved in short order.

Dr. Richmond consoles Judge Kingbury, reeling with the tragedy and the news that his son was gay.

“You’ve sent many up the river, and you know it, Bob,” the doctor says. “But when it hits home it’s a different story. In this civilized world, we are not civilized enough to know why or for what purpose these poor degenerates are brought into the world.”

The judge sighs and agrees to cover up the murder, to preserve his own reputation. “Report this a case of suicide.”

“Yes, your honor.”

The curtain comes down.

When it came down on October 2, 19281, a small army of police officers sitting in Broadway’s Biltmore Theatre sprung into action. There were plainclothes officers guarding the doors, a row of senior officers, and a team of cops who swept backstage to tell the 55-person cast that they had just enough time to change clothes before they would be taken downtown. They were under arrest.

Patrol wagons pulled up and police loaded in the cast, crew, and producer. They aimed to make Pleasure Man a one-night-only production.

Despite her $500 fine and 10-day prison sentence, the play’s author insisted the police “have made a mistake this time.” This wasn’t her first theatrical raid. A judge agreed, and issued an injunction to police, preventing them from busting up the next day’s performances.

That evening, as the cast began the final act, cops rushed the stage. Another court had vacated the injunction. This time, they told the cast, they would have no time to change out of costume.

One cast member stepped into the spotlight as the arrests began. "There are ladies and gentlemen on this stage — at least some of them are ladies and gentlemen — and you know how we are being covered with filth,” he said.

The crowd jeered: "Let him go on. Let him alone."

But the cops hauled them all down to the station. Years of trials would follow.

The author was defiant. “It's just what you think yourself that makes a thing bad. Anybody can find filth in anything. I could find it in childhood prayers if I wanted to,” she told reporters after those early raids.

“They're just trying to make things up about my show. It's got female impersonators in it. What's wrong with that? You can see them any day."

The author and star of the show, Mae West, would be vindicated, eventually. She would go on to become one of Hollywood’s biggest stars.

The law, however, had never been on West’s side. New York’s Wales Padlock law allowed police to raid and close any stage production featuring “sex perversion.” It remained on the books until 1967.

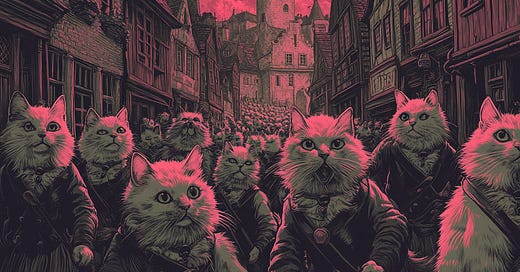

This week, on Bug-eyed and Shameless, a short history of how moral panics over trans people and drag queens have, for more than a century, justified the worst abuses of state power.

While it might be out of fashion now, it was the Germans who came up with our first modern term for drag — transvestitismus. Physician Magnus Hirschfeld used the term in 1910 to define "all people who, for whatever reason, voluntarily wear clothes that are usually not carried by the gender to which they are physically assigned.“2

Conversations about gender became downright revolutionary in Germany, thanks to Hirschfeld’s work. His research had spurred the foundation of the Coalition of Transvestites and the Special Transvestite Group, organizations devoted to those Germans who felt the confines of their biological sex to be suffocating. Magazines devoted columns to this burgeoning community — including one dedicated publication, The Third Sex.

The law, of course, forbade this kind of behavior as indecent. But Hirschfeld had adopted such a scientific rigor to his study of these non-traditional genders that the state, eventually, was dragged into acceptance. With his help, dozens of Germans were issued Transvestitenschein — passes confirming their clinical diagnosis. If they were stopped by police, they could present their Transvestitenschein, which bore Hirschfeld’s signature, and escape prison time and a fine.

When the Weimar Republic rose to power, enforcement of these morality laws declined dramatically. Internal police reports even suggested a departure from the idea that there was a link between cross-dressing and criminality — a hitherto novel idea. (Unless they were engaged in sex work, of course.)

All that newfound acceptance was put to the test inside the Eldorado, in Berlin, where clientele were invited to be themselves — Transvestitenschein included. A gay bar, Eldorado housed a veritable who’s-who of the German arts world: Poet W.H. Auden (who I quote liberally in Dispatch #43), actress Marlene Dietrich (who would go on to become friends with Mae West), and artist Otto Dix. When Christian Schad painted a Viennese aristocrat in 1927, he situated his subject “between an older, somewhat masculine woman and a well-known transvestite in transparent clothes from the Eldorado in Berlin,” Schad wrote. “Why? I thought it was the right thing at the time.”

Author Christopher Isherwood, another regular, styled his most iconic character after a local cabaret singer: Sally Bowles. The Eldorado would serve as an inspiration for the Kit Kat Klub in the stage production of Cabaret, based on Isherwood’s work.

The story goes that one grand dame — “slumming” it at the Eldorado — rudely enquired to one dancer as to their gender. “I am whatever sex you wish me to be, Madame,” they responded.

But the sexual liberation inside the Eldorado took place amid a growing anxiety in Germany. Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers' Party was growing in popularity, and he viewed homosexuality as a cancer on the German state.

Hitler’s brownshirts, the Sturmabteilung terrorized his political enemies, particularly the Communists. They left the Eldorado alone, however — thanks in no small part to the fact that their leader, Ernst Röhm, was a patron.

It wasn’t the Nazi that began the crackdown: It was the Weimar state. Franz von Papen, an ardent Catholic, had been appointed chancellor in 1932. He dispatched his police to conduct “an extensive campaign against Berlin’s depraved nightlife.”

Police didn’t shut down the club right away. First was the 10 p.m. curfew. They came the prohibition on same-sex dancing.

Germany’s illiberals saw an easy target. The nationalist press, including Der Stürmer, attacked Hirschfeld as a core reason for Germany’s supposedly over-sexed culture. The Nazis, in particular, demonized his study of homosexuality and transvestitismus as Jewish degeneracy. Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science was raided by young Nazis — tens and thousands of his books and files were stolen and burned in the street.

Then, in 1933, Hitler came to power. Any owner of a gay bar with any sense shut their doors. The Eldorado’s owner, sensing danger, handed the bar over to one of his most powerful customers: Ernst Röhm. He turned it into a local office for the Sturmabteilung.

The Night of the Long Knives would come for the well-known homosexual, as Hitler worked to consolidate state power. Ernst Röhm was executed on July 1, 1934.

With him gone, Hitler’s true hatred for Queer people was unleashed. The state vilified homosexuality, cross-stressing, and prostitution as all part of the same Jewish conspiracy to make money and spread venereal disease.

Despite their air of morality, the Nazis would go on to create a network of state-run brothels — in practise, regulated sexual slavery. Homosexual prisoners in Nazi concentration camps would be forced to visit the brothels in order to “cure” them of their homosexuality.

Many of the middle class patrons of the Eldorado fled Germany before Hitler consolidated power. Many didn’t. It is estimated that between 10,000 and 15,000 Queer people died in the Holocaust, including, no doubt, many of those transgender people and drag queens who frequented Berlin’s bars and cafes.

There is a disputed fact, for some. One German student tweeted, last year, that recognizing the transgender victims of the Holocaust “mocks the real victims of Nazi crimes.” A Cologne court ruled that tweet denied the reality of the Holocaust.

"Would it be permissible for a man to masquerade as a woman if his intentions were not for any wrong-doing or fraud?" a reader wrote in to the Los Angeles Evening Post-Record in 1934.

The paper, citing chapter and verse of the city bylaws, confirmed that “it is unlawful for any person to wear any mask or any other disguise without first obtaining a permit from the board of police commissioners.”

Many cities and states across the U.S. had similar laws — even just a few articles of inappropriate clothing could be enough to invoke the so-called masquerade laws.

A similar law was on the books in Hawaii, passed in 1963: It specifically criminalized any attempt to use the opposite gender’s clothing to “deceive.” It was adopted, at least in part, thanks to Yappy’s Cocktail Lounge.

The Honolulu joint became infamous because of its clientele. Clad in gowns and miniskirts, the bar-goers caused traffic jams in the city — rubberneckers would drive by to gawp. The popular bar’s owner, a straight father of three, was thrilled at the business, if slightly confused.

But police weren’t thrilled. Hence the law.

So patrons at the bar opted for a simple solution: Buttons on their lapel reading “I’m a boy!”

The buttons notwithstanding, the bar was a haven. "We're happy now that we live openly,” one of Yappy’s clientele told the Honolulu Advertiser in 1968. But the backlash, including sometimes from that very newspaper, was constant. “Why won’t society let us be what we want to be?” Another local Queer said.

The buttons served as protection against the police — much like Hirschfeld’s Transvestitenschein. But, a cop told the Advertiser, "when their hangouts close up, some shed the sign and go looking for trouble." They made many arrests of those caught not wearing their badges, he said. Police arrested hundreds every year under those laws.

This whole concept, hardly new, had rocketed into the mainstream once more. Ann Landers was fielding questions about cross-dressing. A group of doctors proclaimed to have “cured” the compulsion to dress as the opposite sex. (Their secret? Electroshock therapy.)

New York’s version of the masquerade laws would be used to bust, again and again, the drag queens and trans people who frequented Greenwich Village. Even the modestly-dressed would be targets. Women, for example, were required to wear three pieces of feminine attire — cops were more than willing to expose their underwear in order to find out if there was an infraction.

Even the most fashionable gowns were unacceptable. When Police Commissioner Michael J. Murphy attended National Variety Artists gala in 1962, he was so scandalized by some of the dresses that he called in the vice squad. The cops raided the place, haplessly flittering through the crowd on the lookout for law-breakers. ("I'm a woman," one guest barked at a cop, who went on to grab another patron in a black sheath dress.) One partygoer was booked on a count of indecent exposure, while another 43 were charged under the masquerade laws.

A frustration with these arrests culminated in 1969, when undercover cops raided the Stonewall Inn. While the raid was not, technically, about those masquerade laws, the cops had set up a spot in the bar to roughly check the biological attributes of all the female-presenting attendees.

As the patrons were being hauled into waiting vans, the cops grew increasingly violent — one smashed a drag queen in the face with his nightstick. Drag king performer Stormé DeLarverie, while being hauled out, screamed: “Why don’t you guys do something?”

So they did. They rioted.

Sometimes it’s easy to think in terms of Martin Luther King Jr’s endless optimistic call-to-action: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”3

I’m partial to another quote, often attributed to W.E.B. Dubois: “A system cannot fail those it was never built to protect." (In fact, it was penned by Vann R. Newkirk II, a senior editor at The Atlantic.)

No matter how far we come, it seems like the state can always reliably fall back to vilifying trans people and drag queens as an easy out. Just about every excuse has been put on the table to criminalize drag: They’re shoplifters, they’re sex workers, they’re obscene, they’re violent, they’re perverse. They’re so obvious that they’ll convert others, they’re so sneaky they’ll trick unsuspecting suitors.

Each time a new wave of the moral panic crests, the ignorant rise with shock as the calculating look for opportunities.4

And they craft new laws or adapt old ones: They charge actors with obscenity, trans people with masquerading, or bar-goers with deception. Or they bring their dehumanizing to such heights that they simply round up any deviant they can get their hands on.

I’ve written previously how we have spent decades being bombarded by anti-Queer narratives around children (Dispatch #8) and how anti-LGBTQ obsessions drive domestic extremism (Dispatch #37). But we spend too little time talking about how state power has consistently been used to crack down on identities that don’t fit with traditional gender roles. And how, unfortunately, it has been incredibly effective.

Our moral universe may bend towards justice, but this system we’ve got was never built to protect trans people. It was built to criminalize them. Yes, we have RuPaul Charles — and the 1920s had Mae West.

Even as gays and lesbians have ‘made it’ into polite society, the state has used its power to shut down acceptance of trans people. And it’s at it again.

Ron DeSantis has recently dispatched police to raid venues featuring drag queens. He’s vilified and criminalized healthcare for trans people. He’s banning books and research on gender and sexuality.

He’s not the only one: There are 452 anti-LGBTQ bills being proposed across the United States right now. Many have already become law.

History is not a straight march forward. It is not a given that this anti-trans backlash will recede.

It is not hopeless, either. But it’s going to take a lot of work. And maybe a riot.

That’s it for this week! Don’t forget to tell your friends about Bug-eyed and Shameless.

Just a reminder that there is a BE&S chat: Paying subscribers can even start their own threads. (Which you should do!)

I’ll be back next week with something completely different.

I’m taking some creative liberty, here. The excepts above are from The Drag, put up briefly in 1927. The production that was staged in 1928 recast Rolly as a woman, retitled as Pleasure Man. Part of the hysteria around the Pleasure Man turned on the idea that it was a repackaging of The Drag. Both plays share the same sin: Drag queens.

Its English translation, transvestite, is no longer socially acceptable for a variety of reasons: Not least of which because it was often applied to transgender people, whose gender identity goes far beyond just the clothes they wear.

The quote is technically a paraphrasing of Theodore Parker: “I do not pretend to understand the moral universe. The arc is a long one. My eye reaches but little ways. I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by experience of sight. I can divine it by conscience. And from what I see I am sure it bends toward justice.”

J. Edgar Hoover’s war on homosexuality belied the fact that he cross-dressed on occasion.

Wow , this is timely politically and for an event next Sunday

Fairlawn Avenue United Church , Affirm Ministry, in partnership with International Day of Pink, will be hosting Martin Boyce’s cross-Canada Courage to Stand Up tour on Sunday, April 16 at 1:30pm, his only public event in the GTA.

Boyce was a participant in 1969’s Stonewall (or, Stonewall Riots, Stonewall Uprising) in New York City, a pivotal moment in queer/trans history. He remains an activist to this day. The tour is being funded by the U.S. Embassy. Boyce will be interviewed by Michael Coren, Anglican priest, columnist and former broadcaster. Registration with IDOP https://www.fairlawnchurch.ca/dayofpink/ The event is free, there is fundraising request to support our most recent refugee arrival. He came from Cameroon Mar 23.

Read a book many, many years ago called The Pink Triangle. It had accounts of just how badly LGBTQ2S+ were treated in the concentration camps. Worth a read if it can still be found.